We Bought an Average Farm in New Jersey. Or So We Thought.

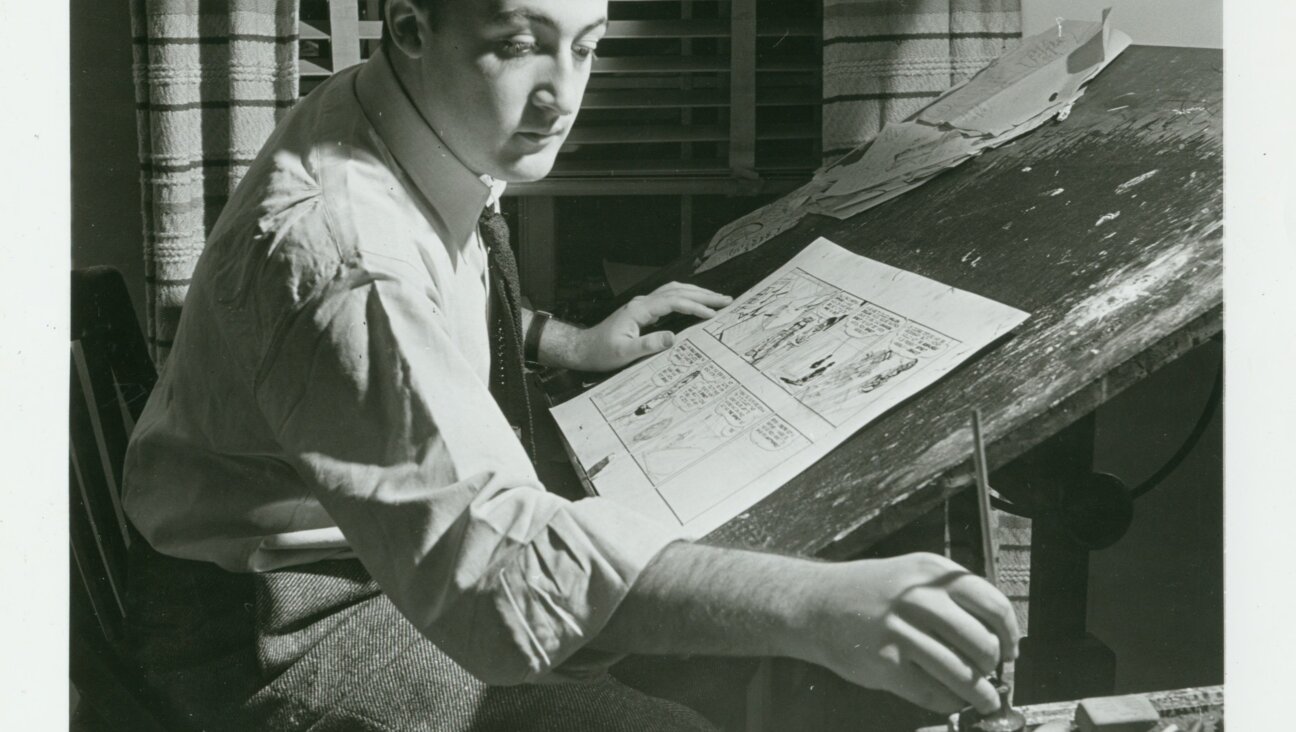

Image by Kurt Hoffman

We were having our Shabbat dinner at “the farm” when, after finishing the chicken soup with lockshen, the poultry dish arrived. My sister Lenore stabbed what she thought was the weekly roast chicken and screamed out, “Henrietta!” Henrietta was our pet duck.

Ours was not a working New Jersey farm, but a summer vacation spot for our Philadelphia family, bought when World War II ended. My gregarious mother didn’t want to abandon the close family relationships we shared, but my father had longed for the agricultural atmosphere he had left behind as a Romanian immigrant.

Little did we know we would be participating in the business life of an American Jewish agricultural colony.

My parents’ compromise was buying a 10-acre “farm” near Vineland and inviting my mother’s siblings and families to summer with us. A Kennedy compound it wasn’t. The town itself boasted only a general store and a gas station/post office. Our home’s original space, which included a living room, kitchen and upstairs bedroom, was extended. Two bedrooms were added for my parents and my grandparents. Plus a working bathroom with a shower. No more outhouse for us.

One aunt and uncle converted a chicken coop into an adorable cottage decorated in yellow and blue. My brilliant Uncle Sam devised what may have been the first solar heating system, placing a water tank on the roof. Warmed by the sun, it provided him a hot shower each evening.

My Uncle Jack, a self-described jack-of-all-trades, started his house from scratch. No chicken coop for him. He built it from the ground up, adding running water and electricity. Only problem was, the whole house tilted to one side.

My Uncle Bennie, the successful owner of a large furniture and appliance store, recycled a bus he had purchased for advertising. It formerly roamed Philadelphia’s streets announcing special sales. Now he brought it to Arost Acres and put it up on blocks. My fancy aunt had her interior designer outfit everything with matching built-ins and fabrics. A unique mobile home.

And my older sister Ella — a Holocaust survivor adopted by my parents — and her husband Victor chose to renovate what we called “the termite house.” The small outbuilding was riddled with termites, but the uncles decided the roof was sound. They worked on propping up the roof, then demolishing the understructure to build a replacement — but poof! The roof collapsed.

Every Saturday night the entire mispocha sat around the outdoor brick barbecue the uncles had built, roasted dinner and sang songs.

Amid all these good times, our house remained kosher. Each week our father took one of our pet chickens or ducks to the shochet in nearby Norma to be slaughtered. That night it had been Henrietta the duck.

Neigh-Sayers: Jacob Crystal in his horse-drawn cart. Image by Alliance Colony Foundation

How did we get those animals? Victor had an egg route in Philadelphia, and his customers assumed the eggs came from his own farm. Christian clients often bought their children chicks or ducklings for Easter. As these pets grew, they became too large for city life, so they gave them to Victor. They then became our pets in New Jersey.

Our family often journeyed into the Vineland area not only for the shochet, but also for the kosher butcher and Goldstein’s kosher deli — and a real supermarket.

And why was there a shochet nearby? Turns out he was part of Alliance Colony, one of the country’s first Jewish agricultural communities, established in 1882 by HIAS and Alliance Israélite Universelle (hence the name). Philanthropists Baron Maurice de Hirsch and Maurice Fels helped as well. Although several publications cite the Alliance Colony as the first American Jewish agricultural colony, JewishEncyclopedia.com claims that the first agricultural colony settled by Jews in the U.S. was founded at Wawarsing, New York, in 1837, and that the country’s first agricultural colony of Russian Jews settled on Sicily Island, Los Angeles in 1881.

Nevertheless, Alliance remained one of the most important. “It was the first successful colony and the longest lasting,” said Jay H. Greenblatt, president of the Alliance Colony Foundation. It began with Jews fleeing Russian pogroms. Greenblatt said the original settlers consisted of 43 families. The colony was situated on the Maurice River, about five miles from Vineland and 40 miles by train from Philadelphia. A memoir by the late Sidney Bailey notes that the original pioneers lived in barracks, slept on straw, and dug out tree stumps. They later lived in “shanties” 14-feet square and 14-feet high and farmed the land. Greenblatt, 78, who still practices law in Vineland, describes their families’ lives as “sweet and simple.”

Greenblatt had planned on becoming a dentist. However, one time when he lectured on raising the community’s cultural level, a rabbi noted his eloquence and told him he should become a lawyer. So at age 17 he enrolled in law school — picking and selling blackberries in the summer to finance his education— and became an attorney in Vineland.

“My father, M. Joseph Greenblatt, woke up at 4 a.m. daily, did his farm

The settlers experienced no anti-Semitism, and were neither bullied nor ostracized.

The settlers experienced no anti-Semitism, and were neither bullied nor ostracized, Greenblatt said. “There were Quaker farmers nearby, and the pioneers couldn’t have succeeded without the fundamentalist Christians, who helped teach them how to plow fields.”

Despite the physical hardships, a primary goal was to give their children an education. “Education was a priority for my father’s generation,” Greenblatt said. “Not only did these families survive, but their descendants contributed greatly to American society,” said Greenblatt. One of Greenblatt’s uncles became a dentist. Joseph B. Perskie, born in 1885 in Alliance, was a member of the New Jersey Supreme Court. The Seldes brothers of Alliance grew to be noted journalists: George Seldes as a war correspondent, and Gilbert Seldes as a critic who became the founding dean of the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. Stanley Brotman, who became a U.S. district judge, was born and raised in Vineland. The town of Brotmanville had been established by his grandfather. Many of the women, including Greenblatt’s aunt, Molly Greenblatt Kravitz, became teachers.

Later, a small group of immigrants fleeing Nazism settled in the colony “because there were already synagogues there and people who spoke their language,” Greenblatt said. After World War II, the Jewish population again swelled with new immigrants. Eventually, it claimed about 1,200 Jewish families, many in the chicken and egg businesses.

“Alliance was a springboard,” said Greenblatt. “People who had been downtrodden and oppressed could rise above it and succeed.”

However, the next generation didn’t stay. Many went away to college and found partners there. Although they didn’t marry descendants of other colonists, most married Jewish spouses. What remains is the Tifereth Israel synagogue built in 1889, one of four synagogues, according to Bailey, and one of the country’s few extant 19th-century synagogues. The cemetery also remains, harboring more than 5,000 graves.

Greenblatt said he organized a celebration of the colony’s 100th anniversary, along with a committee of pioneers’ children. “About 2,000 people attended,” he said, “including 600 descendants of the pioneers.”

No matter the difficulties, the fresh air and simple farm life must have been healthy for the settlers, since many lived for more than 100 years. The oldest survivor of the original settlers is Lillian Greenblatt Braun, Jay Greenblatt’s aunt, who is 109. (Unfortunately, she was too ill to be interviewed for this article.)

Recently, descendants attempted to create a Jewish heritage center in the home of colony founder Moses Bayak to commemorate the community’s history, the history of Jews in America, and their participation in farming. However, lack of funding has so far halted the process. Greenblatt said three county federations, the chevra kadisha of Alliance, and the Alliance Colony Foundation arranged for a half-million-dollar matching historic grant, but the community couldn’t raise the matching amount due to the economic downturn.

This project would honor the courage and intelligence of these early pioneers, who gave back much to this country that offered them a home. Greenblatt said, “It was a farming group that planted in the fields and planted a crop of children.”

Molly Arost Staub, a former editor at Palm Beach Jewish World, has visited 125 countries and discovered Jewish stories in most of them.