On 15th Anniversary Of 9/11, Sculptor Shows City In Mourning

‘I think when anyone ever grieves or thinks they think in their own vocabulary’

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

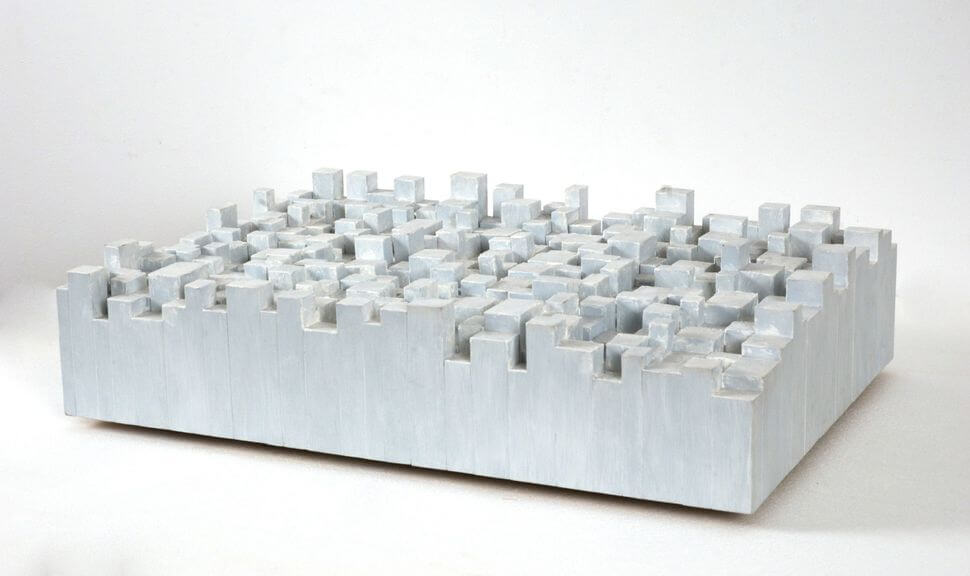

In 2011, the New York-based sculptor and painter Tobi Kahn created a meditative space at New York’s Educational Alliance to reflect on the tenth anniversary 9/11 attacks. Kahn specializes in such spaces, which he designs to promote, in his words, “healing.” The exhibit at the Educational Alliance, titled “Embodied Light: 9-11 in 2011,” centered on the sculpture “M’AHL,” a low-rise rectangle cut in relief to resemble Kahn’s memory of the view of Manhattan from the World Trade Center’s Windows on the World.

For the upcoming fifteenth anniversary of the attacks, “M’AHL,” which is assembled out of of twelve individual sections, will be exhibited as a whole for the first time since its debut as part of the 9/11 Memorial and Museum’s exhibit “Rendering the Unthinkable: Artists Respond to 9/11.” Kahn is one of thirteen artists included in the show. Other works on display include the Jewish painter, sculptor and printmaker Eric Fischl’s sculpture “Tumbling Woman,” a group of the 2,996 paintings Manju Shandler created to commemorate the attack’s victims, entitled “Gesture,” and the Blue Man Group’s video “Exhibit 13.”

Kahn spoke with the Forward over the phone about “M’AHL,” “Embodied Light,” and the process of creating art responding to 9/11. The following is an edited version of the conversation.

“M’AHL” appears as part of Tobi Kahn’s 2011 installation “Embodied Light: 9-11 in 2011” at New York’s Educational Alliance. Image by Tobi Kahn's Studio

Where did you find inspiration for “M’AHL?” How did you decide to make it the center of “Embodied Light?”

After 9/11, all the photographs you saw from down there everything was covered in ash, it had a grayish cast to it but it also looked white, like holiness. It was very strange to look at something that was pure destruction but looked like it was in mourning, I felt like it was shrouded. My mother was buried in a shroud, and that white feeling was very powerful, and I felt it very powerfully, and I wanted the city to have that feeling.

I wanted the center of the piece to be made like you were looking at the city. All the images I remembered, it was all white; it had the reflection of the sky. It was a very powerful piece to do. I built seven shrines for seven days of the week; everything that I did had a Jewish significance to it. I happen to be an observant Jew. My work comes from that. I’m also very interested in interfaith work so I wanted to make things that everyone could agree with.

I wanted to pay homage not only to the people but to the building, to the city. I’m always interested that when you go to visit a shiva house you’re not allowed to speak until the person speaks to you. It took me that long to make the piece because there was nothing I could possibly say in the beginning that I thought could be healing to anyone.

Did seeing “M’AHL” as part of a collection of pieces responding to 9/11 change your understanding of the piece?

I think when anyone ever grieves or thinks they think in their own vocabulary. I found that interesting. No one’s work looked at all the same. That was important to me, that it didn’t feel rote, that this is the recipe of how to make a September 11th memorial.

Why is “M’AHL” in twelve pieces?

I thought a lot about the twelve tribes, and what does [it] mean to be a witness. Each person sees things in a different way. I felt that this is something I want people to remember all the time, and I think there’s something about doing personal prayer and communal prayer and I felt I wanted both. So in between exhibitions twelve different people would have it in their homes, and the condition was when people bought the work, that they would have to loan it back for exhibitions.

A section of Tobi Kahn’s 2011 installation “Embodied Light: 9-11 in 2011” at New York’s Educational Alliance. Image by Tobi Kahn's Studio

Where did you find inspiration for the meditative space of “Embodied Light?”

Once they gave me this gorgeous space to work on, I thought about what I would want to do, and I decided that I wanted to treat it like a very religious act and think about what shiva is and what memorial means. I started thinking about the fact there are yahrtzeit lights. There are different lights I’ve made – I did quite a few things for the Shoah, when it’s communal death – I wanted to treat those experiences with their own dignity.

What, for you, is the significance of continuing to remember and reflect on 9/11 through art?

I heard that Napoleon once came and saw people mourning over Tisha B’av. I don’t know if this is true. Basically, he said “When did this happen?” and they said “2000 years ago,” and he said “This is a people that will continue because they remember.” I take everything very seriously because if you don’t remember you never learn from the past. I wanted to be able to do a piece that was about remembering and understanding what we lost.

Talya Zax is the Forward’s summer culture fellow. Contact her at [email protected] or on Twitter, @TalyaZax