The Aphorism Master

Yes damns no. No postpones yes.

Tragic facts don’t exist.

The magic of fiction lies in deluding reason that it is fiction.

All ways lead to the wayfarer.

The long lineage of literature’s shortest form, the aphorism, extends from the mythical Hippocrates of Greek antiquity, through the Renaissance, Erasmus and Paracelsus, into the modern Europe of Montaigne and the great G.C. Lichtenberg. In the early 20th century, Viennese Jew Karl Kraus introduced a vicious satire to the form, in doing so further polishing the history of the sentence-length stones that he cast at everyone from archdukes to draymen. In our millennium, a time of reduction and minimization, the aphorism has rightly returned. Its master is Róbert Gál.

Born in Bratislava, Slovakia, in 1968 and now living in Prague, Gál is a phenomenon unto himself: a purveyor of neurotic philosophy encapsulated in elliptical portents and epifragmentals, the content of which is at all odds with their length.

“I like the aphorism,” Gál said at a recent interview in wintry Prague, “because it joins serious thinking (a source of philosophy) with sudden inspiration (a source of poetry).”

But does that mean he’s a writer or that he’s a philosopher? Or both?

“My uncle Egon — who is a philosopher — would have said that it’s much easier to be ‘a writer’ than to be ‘a philosopher,’ because as a writer you don’t have to entertain the many meanings a text might offer; you can often put aside concrete language or names in favor of other concerns.”

One question begets an answer of a thousand questions — such is Gál, less an artist to be read than an artist to be read and reread yet again, and again.

Indeed, his texts — a handful of books in Slovak, in addition to a recent English translation, “Signs & Symptoms” (Twisted Spoon Press, 2003) — insist on refuting categorical imperatives; as the great German writer Hölderlin once described himself, Gál, too, is “a mortal enemy of all one-sided existence.” With influences ranging from Nietzsche to E.M. Cioran, from Dostoyevsky to Gershom Scholem to John Zorn, Gál palpably delights in linguistic subversion, the manic manipulation of clichés; cross-genre references, and an almost outdated, parodied modernism — all in order to imbue his short lines with an immediate depth that is impossible to achieve in any longer form.

An indirect proof of God’s existence is God’s indifference to human fate.

When we sat down at a café to discuss his recent work, I mentioned the alchemical, almost kabbalistic densities — linguistic and of pure thought — to be found scattered with rigorous abandon throughout his work. Thinking to lead our interview to a discussion of the Jewish element in what he does, Gál went on to address this identity of his — one of many — through his colorful, and at times painful, biography.

He explained that in the early 1990s, “I was first forced to encounter my Jewishness after my father, Fedor — who was born in the concentration camp at Terezín — began to be harassed in Slovakia. He was the head of the political party that won in the first free elections after the Velvet Revolution. That abuse led him, and his family, to leave Slovakia and to start anew here in Prague. It was that traumatic experience which opened up the question of my identity, even though my mother is not Jewish.”

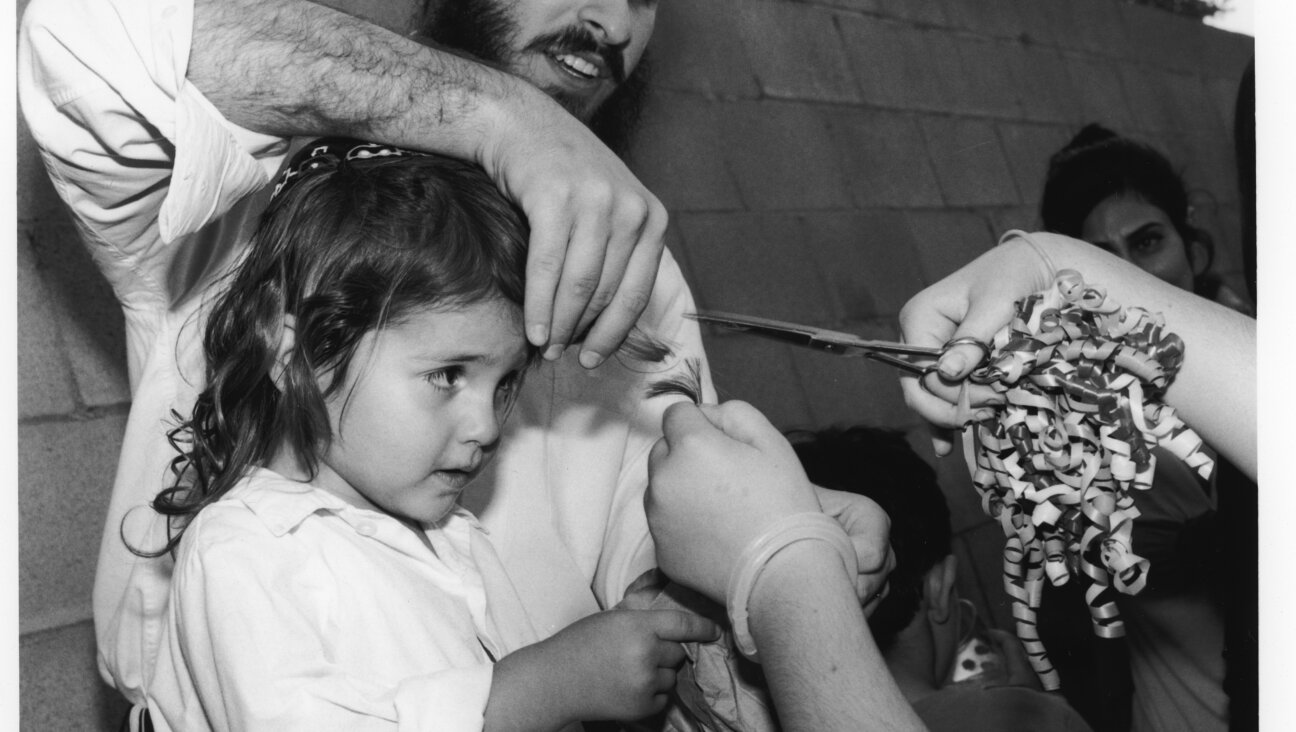

Gál immigrated to Israel in December 1995 and became an Israeli citizen, an act that today he considers a “gesture.” But, as with any artist, his biography evolved, whether consciously or not, into subject, even when refracted through a mind intent on abstraction. Citing the work of Jews like Kafka, Benjamin, Derrida and Jabes, Gál asserts that Jewish writing and thought was always the work “of social outsiders, of great writers, and thinkers, who lacked roots.”

“I never felt rooted in Slovakia,” Gál said, “though I was born there and lived there for more than 20 years; I never felt rooted in any other place either, including Israel. The best place in the world for me is the place where ‘rootlessness’ is party to the ‘open mind’ in every respect — that’s my idea of New York, an aesthetic which I would like to import to Prague.”

Talk led to New York, the city where Gál spent some time as a student (at the New School), the current capital of Jewish art and thought. Sitting in a café in Prague, once a city with a most vibrant heritage of Jewish artists and minds, Gál seems to be at an impasse — a historical impasse that makes itself felt no less personally.

Most books written in Slovak, especially those of literary philosophy (if that’s what Gál’s are), hardly sell enough copies for the author to afford a few for his friends. Despite a dearth of reliable literary translators from Slovak to English, Gál hopes to find one day a niche in the wider philosophical world, even if that means translating his own works. To that end, he seems to regard a Jewish connection with New York — a connection of the intelligent past with the acting present — as one of paramount symbolic importance to his work.

“In recent years,” Gál said, “I have been strongly inspired by the composer and musician John Zorn, who, on the cover of every Masada Quartet studio album, quotes Scholem’s words: ‘There is a life of tradition that does not merely consist of conservative preservation, the constant continuation of the spiritual and cultural possessions of a community. There is such a thing as a treasure hunt within tradition, which creates a living relationship to tradition and to which much of what is best in current Jewish consciousness is indebted, even where it was — and is — expressed outside the framework of orthodoxy.’”

His question chose him as the answer.

Gál’s apparent goal, then — because he has not forsaken his second home, Prague — seems to be one of modernization; a streamlining of thought in this city still intellectually ravaged by communism. In its progressive nature; its almost obsessive need to streamline language, modernize terminology and reposition thought itself, and in its refusal to capitulate to the intellectually stagnant “democratic” rhetoric still prevalent in Czech and Slovak philosophical writing 15 years after the Wall, Gál’s work reveals a strong political element: It seeks to restore to the polis a measure of mindful integrity, though an integrity more mutable, or protean, than any previous. In this sense, Gál’s work reveals a political element in that it seeks to restore to the polis — a measure of mindful integrity, though an integrity more mutable, or protean, than any previous.

Can, or should, a philosopher be active politically and still remain a philosopher?

“I don’t know,” Gál said. “Ask Plato… or Václav Havel.”

But Gál, despite his political patrimony and ideals, is an artist. And it’s because of this that his revolution sequel, to be even more “Velvet” than its predecessor, is being undertaken through texts; through a revivifying of the intellectual impetus of dissent, this time around stripped of any ideological agenda for or against a mode of governance or appeasement, and also fully insured — through its deep tradition, if not by its uncompromising nature — against becoming a commodity.

To be sure, his is a position without a position, a nowhere that’s everywhere, a platform with its own trapdoor. Gál’s writing and thought is a future’s blank manifesto, a prayer in favor of all or of none; it traffics in a precise ambiguity that’s best exemplified in one of his most Easternly apt, if almost too open, aphorisms:

Nonetheless, such a purification takes entire lifetimes to manifest….

Joshua Cohen is an editor of the Prague Literary Review, and arts editor of the New York Press. A translator who is the author of a recently published collection of stories, “The Quorum” (Twisted Spoon Press), he was shortlisted for the 2005 Koret Young Writer on Jewish Themes Award.