Why This ‘Honorary Jew’ Deserved The Nobel Prize For Literature

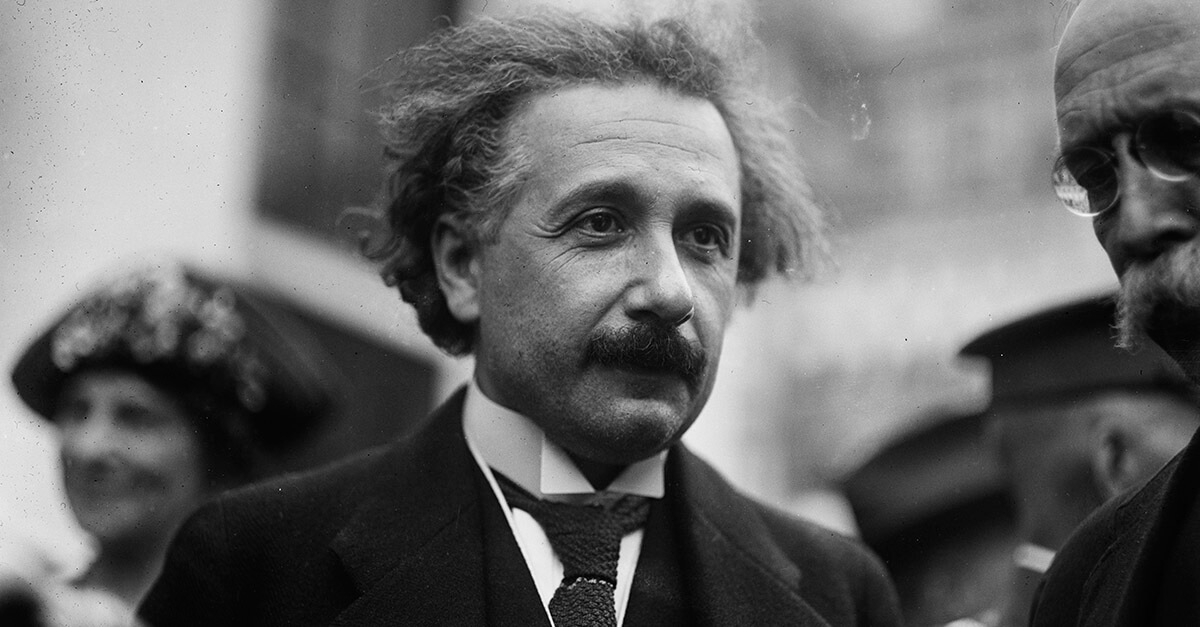

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Although last year’s Nobel Prize in Literature went to a deserving Jewish candidate, in some respects the prize-giving and receiving process was a shondeh, that ever-current Yiddish word meaning disgrace. Not least when Bob Dylan, the honoree, plagiarized portions of his Nobel Prize lecture from SparkNotes, an online version of CliffsNotes, according to [Slate.] (http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2017/06/did_bob_dylan_take_from_sparknotes_for_his_nobel_lecture.html)

Favorites for this year’s prize, to be announced on October 5 include Kenya’s Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Japan’s Haruki Murakami. Another is Claudio Magris, an Italian Germanist, essayist, and critic who has referred to himself as an “honorary Jew.” That’s because his literary career, including such highlights as “Journeying,” “Microcosms,” and especially “Danube,” was much inspired by Yiddishkeit.

BREAKING NEWS The 2017 #NobelPrize in Literature is awarded to the English author Kazuo Ishiguro pic.twitter.com/j9kYaeMZH6

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 5, 2017

“Danube” is an evocation of the Central European river, paying tribute to such writers as Franz Kafka, Elias Canetti, and Joseph Roth. Magris offers a message of international unity and cooperation at a time of world border closings, Brexit, and ultra-nationalism. A chipper 78-year-old, Magris battles against Babel and other forces that separate people. In German- and French-language interviews, he is almost as voluble as in his native tongue, although his spoken English remains relatively deliberate and lumpy.

English language readers may nonetheless savor in translation his complex, elusive novels,. Still untranslated are many of his essays and book-length literary works such as “Far From Where?: Joseph Roth and the Eastern Jewish Tradition”, placing the Austrian Jewish author born Moses Joseph Roth in a tradition with Sholem Aleichem and Isaac Bashevis Singer. Magris is a native of Trieste, the northeastern Italian city close to borders with Slovenia and ex-Yugoslavia. Trieste’s strong legacy of Jewish writers includes Italo Svevo, the novelist born Aron Ettore Schmitz, and the poet Umberto Saba.

As Magris told a gathering at Paris’ Museum of Jewish Art and History in 2009: “[Joseph] Roth gave me the opportunity to get close to Eastern Jewish culture… A fundamental aspect of my book is the fascinated view of [Eastern Jewish culture] particular to non-Jews or assimilated Western Jews. Think of [Franz] Kafka’s admiration for Yiddish actors.” For Magris, Jewish tradition is “intact…something that, despite all the damage, is not really damaged. This strength fascinates me, especially when I compare it to Nazism.”

In 2010, he further told an interviewer at the Centre Pompidou in Paris that the title “Far from Where?” was drawn from an anecdote in which two East European Jews are discussing emigrating to Argentina. One comments, “That’s far!,” to which the other replies, “Far from what?”

Magris exclaimed:

“This is a Talmudic answer, answering a question with a question; it means that on the one hand, the Jew living in exile is always far from everything, because he has no homeland, so he lives in exile, but it also signifies that without a homeland, he lives not in space but in time, in the Book, in tradition, in the law, and is never far from anything. I was very interested in this [Jewish] civilization. It is a civilization that has suffered with extreme violence uprooting, exile, persecution, the threat of annihilation of identity, but which has responded with extraordinary individual resistance.”

One such survivor is featured in Magris’s 1991 novel “A Different Sea.” The story is a fictionalized portrait of the Italian Jewish philosopher and painter Carlo Michelstaedter, another luminary from northeastern Italy. “A Different Sea” discusses the murder in Auschwitz of the family of Michelstaedter, who is described as seeing “light where others saw only darkness…his sunlight is stronger even than Parmenides or Plato, and its rays go farther.” Michelstaedter’s untimely suicide in 1910 was an “explosion” of “ancient Jewish grief,” but the fate of his mother, killed at age 89, required the “complete panoply of the Third Reich.”

Small wonder that in a interview from 2008 with the Italian Jewish author Alain Elkann in La Stampa, Magris declared: “I feel like an honorary Jew,” admiring a civilization “full of religiosity, but irreverent religiosity.” He is also a devotee of the Austrian-French novelist and psychologist Manès Sperber and the Romanian-born Israeli novelist Aharon Appelfeld, both much preoccupied with European Jewish experience around the time of the Second World War. As Nicoletta Pireddu, a professor of Italian and comparative literature at Georgetown University, has pointed out in a pioneering study, Magris “challenges ideological absolutism” through his fascination with crossing borders and multiplicity of cultural references. At a time of international acrimony, Magris’s pan-European approach is a reply to those who divide and separate humans, informed by his understanding and appreciation of Jewish culture. In 2009, at the Quirinal Palace in Rome, Italy, he stated: that the “Jews speak on behalf of everyone.” He cited a missive included in Walter Zwi Bacharach’s “Last Letters from the Shoah” in which a loving Jewish father, on a train to Auschwitz, had the presence of mind to write to his young sons, advising them to avoid icy drinks when they were perspiring. Magris noted that compared to this father,

“The Third Reich appears not only atrocious, but also miserable hyperbole, bloody clownishness… The Shoah was not only Jewish but universal; the abjection of hate and contempt for Jews shows the infamy and imbecility of hating and despising any human community. A Shoah is always possible; it is always lurking everywhere, against anyone… Jews who have faced the Shoah and founded Israel should teach, forever, not to despise any individual or people, because every individual or people despised and humiliated gives, first and foremost, a lesson of dignity and courage… Nazism wanted to destroy diasporic Judaism, one of the great civilizations in the history of the world, bigger and wider than any other frontier, universal because it was able to remain itself, more and more enriched by other cultures and capable of enriching them. One of the many distortions at the base of anti-Semitism is alleged Jewish extraneousness – as if…Heine, so profoundly rooted in Judaism, had not expressed, as Bismarck recognized, the deepest German soul in his Lieder, thus revealing himself as one of the most German among German poets. As if Primo Levi were not one of the greatest Italian writers.”

The Nobel Committee for Literature would go far to erase memories of last year’s Dylanesque comedy of errors by awarding the prize this year to Magris.

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.