The Secret Jewish History of Blade Runner

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The long-awaited sequel to the 1982 sci-fi classic “Blade Runner” opens in theaters October 6. “Blade Runner 2049” picks up the original story 30 years after the events recounted in the original, which was set in 2019.

For those who don’t remember, and for the very few who never saw it, “Blade Runner” was a dystopian sci-fi movie about a bounty hunter named Rick Deckard, played by Harrison Ford. His prey was renegade androids, or “replicants.” These remarkable humanlike robots were manufactured to work as slaves in space colonies. Apparently things didn’t always go as planned up there, and some made their way back to earth, where a well-trained crew of “blade runners” working for the Los Angeles Police Department lay in wait to find and “retire” them.

As with most such stories of humanoids created by man, echoes of the legend of the Golem abound. “Blade Runner” is yet another variation on the original story of a man-beast fashioned out of clay and given powers that lead to unintended consequences, along the way raising questions about what it means to be truly human. Deckard, facing off against manmade creatures so humanlike that he grows a romantic attachment to one, finds himself locked in an existential crisis, not made any easier after a replicant he has been hunting saves Deckard’s life before sacrificing himself.

The original “Blade Runner” is a loose adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s 1968 noir-ish sci-fi novel, “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” In Dick’s novel, the corporation that manufactures the androids is called the Rosen Association. When Deckard visits Rosen headquarters, he is greeted by Rachael Rosen, who thinks she is the daughter of CEO Eldon Rosen. In a metaphorical lifting of her veil, Deckard tests Rachael’s empathy levels, revealing that in fact she is a Nexus-6, the latest model of android — the same model as those he has been ordered to eliminate.

In Ridley Scott’s original “Blade Runner,” the Rosen Association is renamed the Tyrell Corporation, in what could be considered a case of whitewashing or a concerted attempt to de-Judaize the evil capitalists — although Rachael maintains her name. In the novel, a character called Isidore befriends the beings from up above and, like the biblical Lot, protects them from the blade runners. In the film, the role of Isidore is given to a gene-splicer named Sebastian.

In both the novel and the film, Deckard’s final battle is with an android named Roy Batty. In the film, the role was memorably played by Dutch actor Rutger Hauer, whom no less an authority than Dick himself praised as “the perfect Batty — cold, Aryan, flawless.”

Both the book and the film avoid any clear and unambiguous notion of white and black, good and evil. Deckard is on the one hand a killer for hire, but on the other hand he is deeply disturbed by the ruthlessness with which androids are used and abused. And, in a subplot, Deckard is an animal lover in a world in which animals are almost entirely extinct (hence the “electric sheep” of Dick’s title). In the book, Deckard is a Noah-like caretaker who blows his bounty on the purchase of a rare, expensive Nubian goat.

The androids themselves are both victims and perpetrators. Having been manufactured and programmed by humans, they ostensibly have no will of their own, no conscience and no soul. Yet their determination to leave the space colonies and return to earth suggests that they have developed human instincts, if not full-fledged emotional lives. Even when they are defying their creators, they seem to be doing so out of some innate sense of having been harmed and in pursuit of justice.

In a short film released in July, meant to fill in some of the gaps between the original and the sequel, we were introduced to a new character, Niander Wallace (played by Jared Leto), who is an even madder scientist than Tyrell. When he introduces a new line of replicants to a skeptical group of government officials, he says, “This is an angel… and I made him,” lending support to those who see Deckard as a Jacob-like figure who wrestles with replicants-as-angels, while loving a woman named Rachael.

The sequel will explain the ultimate fate of Deckard and Rachael, who, at the end of “Blade Runner,” drive away from apocalyptic Los Angeles — where the sun never shines, where it always rains and where there is no naturally occurring wildlife — on their way toward a happier, greener, Edenic-like world.

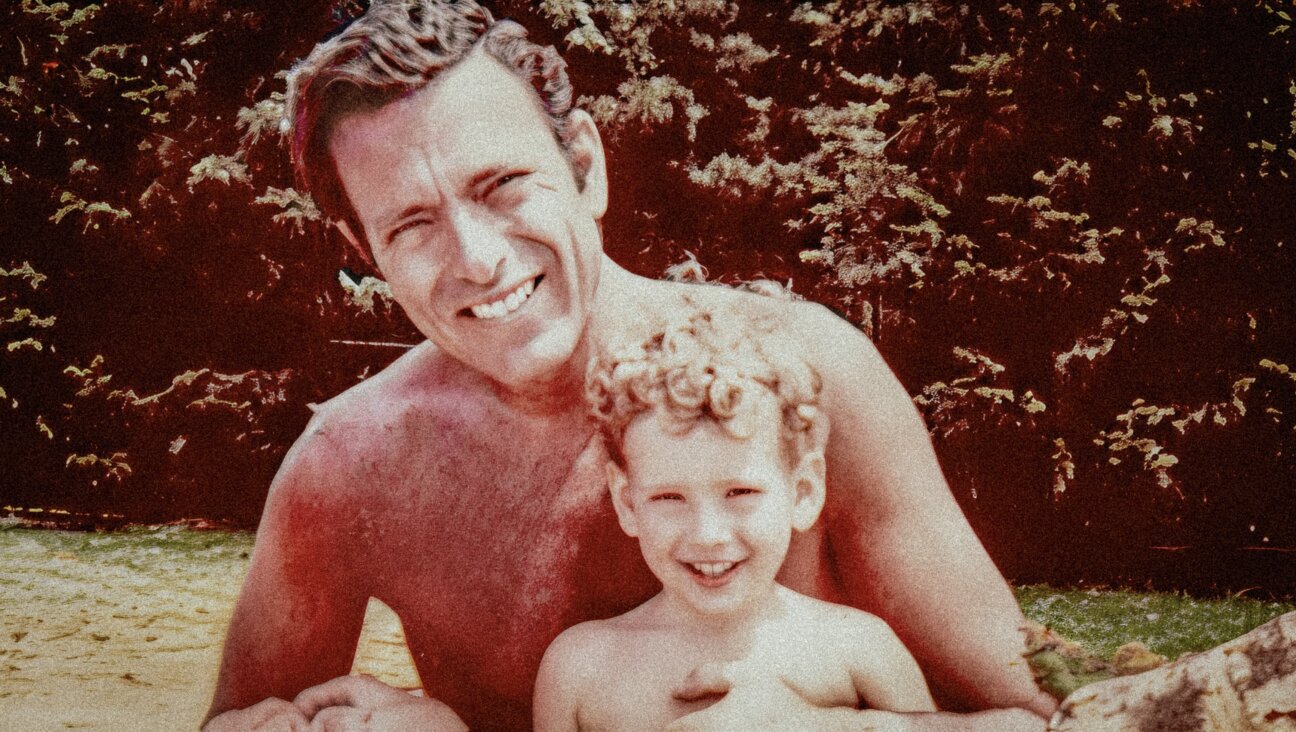

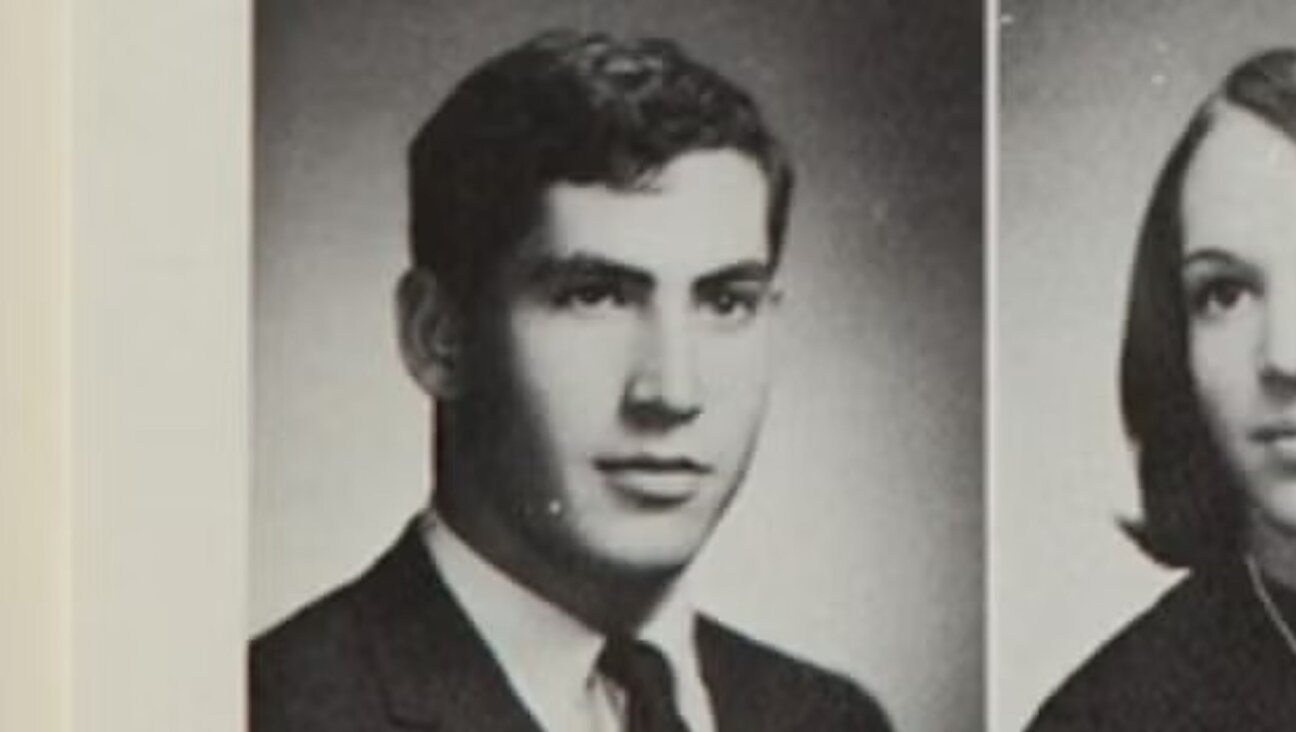

In “Blade Runner 2049,” Harrison Ford — who is the grandson of Harry Nidelman and Anna Lifschutz, Jewish immigrants from Minsk, and once said, “As a man I’ve always felt Irish; as an actor I’ve always felt Jewish” — returns in his role as Deckard.

Seth Rogovoy is a contributing editor at the Forward.