The secret Jewish history Of Hans Christian Andersen

The fabled author of fairy tales may have had a philo-Semitic streak.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

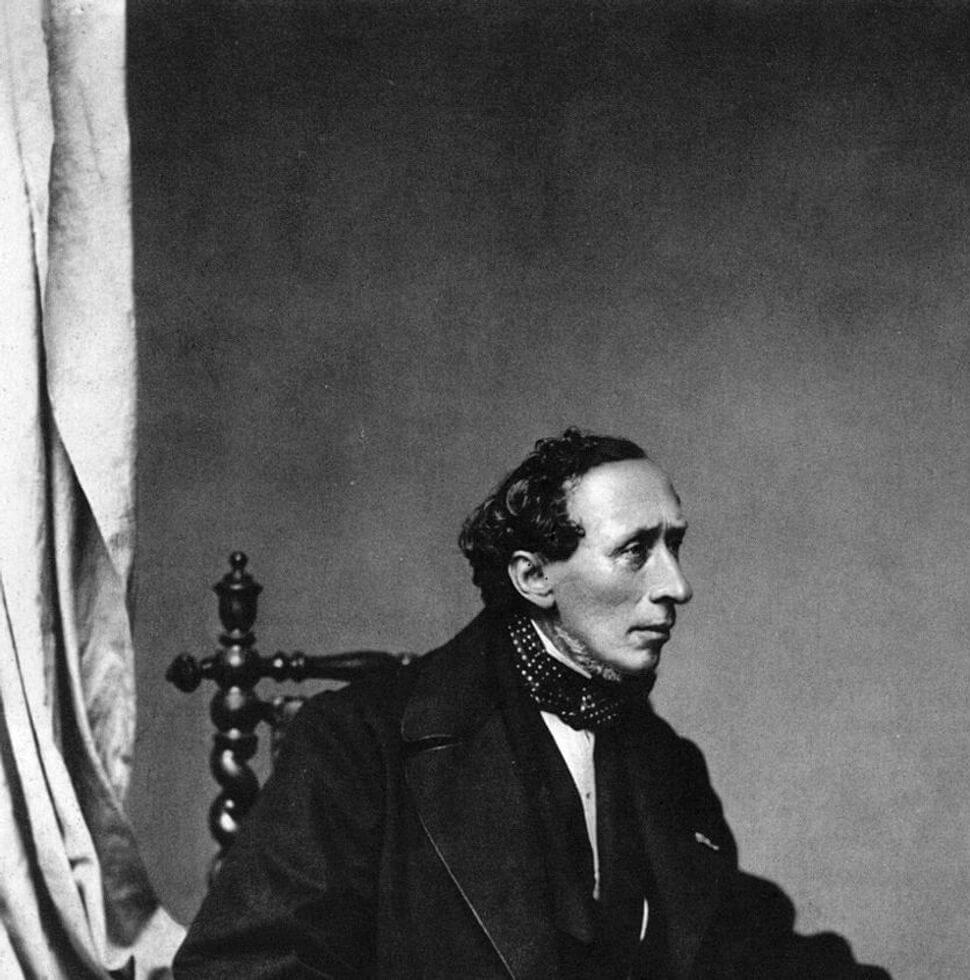

Hans Christian Andersen’s first book of fairy tales first appeared on May 8, 1835. This article was originally published in 2019.

Hans Christian Andersen, the famed Danish author of The Ugly Duckling and The Little Mermaid, once wrote a story called “The Jewish Girl.”

This information on its own might raise alarm given the time and place in which Andersen was writing: 19th century Europe, where Jews in literature hadn’t evolved much since the time of Chaucer. But some scholars suggest the short story is, in fact, evidence of Andersen’s philo-Semitism, even if it might offend a modern reader.

The story, written in 1855, concerns a young Jewish woman named Sarah, who, as a child, excels in a charity school but is made to leave because of the school’s Scripture classes. The child’s teacher observes that Sarah is eager to learn the Gospels and tells her father he must either remove her from school or allow her to become a Christian. But Sarah’s father, who promised her mother on her deathbed that their daughter would not receive a Christian baptism, tearfully, removes her.

Lacking a quality education, Sarah grows up to become a servant. She continues to honor her mother by not engaging with Christianity, though she retains fond memories of hearing the New Testament in her school days.

“Still I have not been baptized!,” Sarah cries, after hearing her master read a legend of a Turk who begs to be converted while facing death at the hands of a Christian knight.

“They call me ‘the Jewess’; the boys of the neighborhood mocked me last Sunday as I stood outside the church door and looked in at the burning altar lights and the singing congregation,” Sarah continues in Jean Hersholt’s translation. “Ever since my school days, up to this very hour, the power of Christianity, which is like a sunbeam, and which, no matter how much I close my eyes, penetrates into my heart. But, my mother, I will not bring you sorrow in your grave! I will not betray the promise my father made to you; I will not read the Christian’s Bible! Have I not the God of my fathers? On Him let me rest my head!”

Though Andersen has sympathy for Sarah, he adheres to a Christian belief that Christ is the sole path to salvation. That belief was not uncommon in Andersen’s time, but the empathy expressed for her was in scarcer supply.

As Andersen biographer Jackie Wullschlager told the Forward in 2001, the author presented his Jewish characters with “sympathy and interest at a time when caricature was the norm.”

Indeed, even in “The Jewish Girl,” Sarah’s unnamed father is treated with a degree of dignity for keeping his promise and not – as was the more common practice – as being obstinate in the face of the newer faith. Andersen describes him as a “poor but honest” man who weeps over having to remove his daughter from school.

Andersen lived the opposite scenario of his character — he briefly attended a Jewish school in Odense. His mother transferred him there after a teacher at his previous school beat him.

“It was the only school he had good memories of,” Wullschlager told the Forward, and Andersen only left because the school shut down.

In his youth, Andersen also had a Jewish sweetheart named Sara, who broke off their relationship when the future fable-writer promised to employ her in a castle he hoped to purchase. Sara interpreted this vow as evidence of a delusion of nobility that ran in Andersen’s family.

The Sarah of the story comes to a tragic end, dying young and receiving a burial outside the wall of the cemetery with non-Christians. But Andersen offers hope, noting that Christian hymns still reach the site of her grave, offering hope for her elevation to a Christian heaven.

While Danish scholar Erik Dal, in his paper “Jewish Elements in Hans Christian Andersen’s Writings,” asserts that the story “balances tactfully” the Jewish tradition and Andersen’s own Christian belief that the New Testament and Christ’s teachings supersede the Hebrew Bible.

But scholar Bruce H. Kirmmse, the former chair of Connecticut College’s History Department, argues in his own paper in Rambam, a scientific journal of Danish Jewish history, that the story was condescendingly tolerant of Jews. Dal rebuts this assessment by saying that Andersen’s views were in fact progressive and philo-Semitic for his time. Reading the story today, it’s not unreasonable to read both views as valid, but in observing Andersen’s life and larger body of work, his intentions seem at worst a bit confused and at best notably respectful of Jews.

Beyond “The Jewish Girl,” Andersen wrote about Jews in ways that Dal contends were unique for his age. Sometimes Andersen’s Jewish characters were simply incidental, but occasionally their presence was evidence of a reverence for the Jewish people and their faith.

Dal notes that Andersen included a “Byronic, passionate” Jewish character named Naomi in his 1837 work Only a Fiddler, whose faith is not remarked upon but taken for granted. In 1857’s “To be or not to be,” Andersen presents a religious pluralist named Esther who ultimately converts to Christianity and, like Sarah, dies young – a disturbing trend. In a less loaded instance, Andersen’s 1870 novel Lucky Peter features a singing master who quotes proverbs from the Talmud. His Judaism, Dal states, is not a plot point, but rather ”an expression of Andersen’s feelings for Jews of high human quality.”

More troublingly, Andersen’s 1847 drama, “Ahasuerus” is about The Wandering Jew, a familiar anti-Semitic character from folklore doomed to travel the world after mocking Jesus on the way to his crucifixion. Dal believes that Andersen, rather than deriding the figure as other writers had, “displays the solidarity of the lonely man and untiring traveler, Andersen, with the damned figure from legend”

Later in his life, Andersen befriended a number of Jews, whom Wullschlager believes found a kindred spirit in the gawky and eccentric writer with a penniless past.

“They probably also identified with his being an outsider,” Wullschlager said. “You are at the heart of the culture, and yet not quite accepted, always a bit different…. Andersen felt the same way, having crawled up from the sticks.”

Andersen moved into the estate of prominent Danish Jewish merchant and member of parliament Moritz Melchior – an ancestor of former Israeli Deputy Foreign Minister Rabbi Michael Melchior – and dictated his diary entries to Melchior’s wife, Dorothea, when he took ill and could no longer write.

In 1875, Andersen died at the age of 70 at the Melchior’s home near Copenhagen. While we can’t find evidence of it, we like to think the Melchiors said the Mourner’s Kaddish. If Andersen believed Sarah deserved a Christian send-off, we hope he received a Jewish one.