Barbara Probst Solomon Was A Fixture Of Literary New York — And My Friend

Nationalist troops give fascist salute while marching in Madrid, Spain, on March 31, 1939. Image by AFP/Getty Images

Barbara Probst Solomon, a prominent novelist and essayist, died on September 1. She was 90.

I first met Barbara in Lyon, France at the 1987 trial of the SS interrogator Klaus Barbie, the infamous so-called “Butcher of Lyon.” She was covering the trial for the Spanish publication Cambio 16, and I was producing the Marcel Ophuls documentary “Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie.” Though of different generations, we instantly connected over our assimilated Jewish upbringings in Manhattan and a shared devotion to intellectual life and adventure.

“Short Flights” by Barbara Probst Solomon. Image by Courtesy of Viking Adult

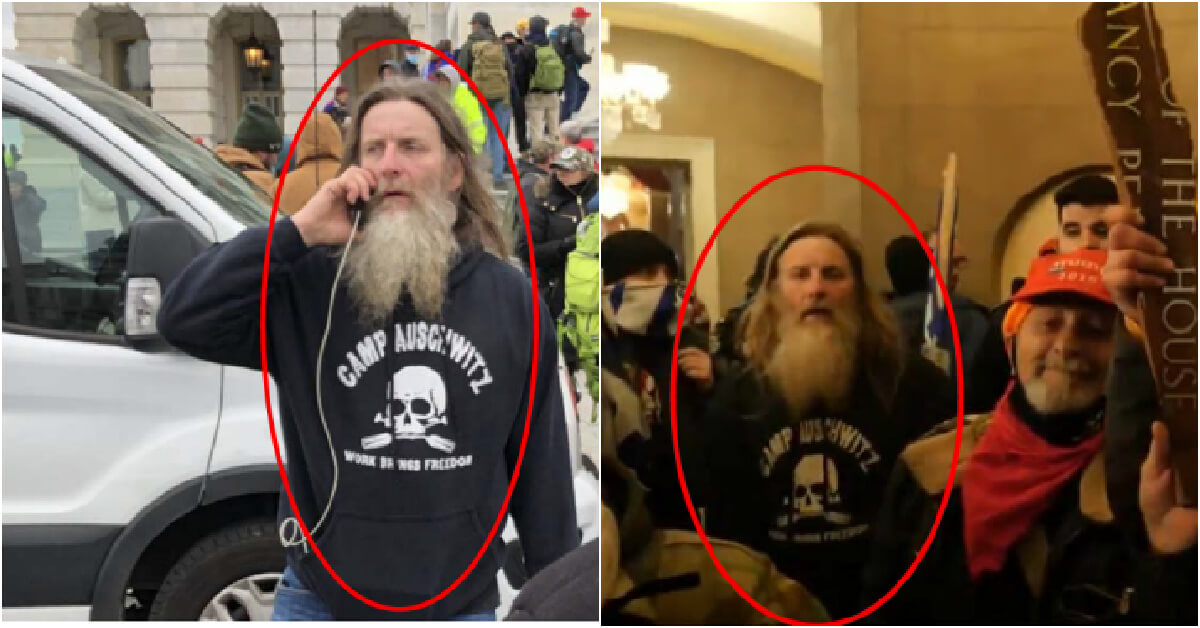

Barbara and I discussed issues raised during the Barbie trial for years after it had concluded: why and how former prominent Nazis escaped punishment in Germany; ongoing anti-Semitism in France; and the American government’s employment of ex-Nazis after the war.

Barbara’s preoccupation with the Holocaust began in Europe some 40 years before we met. After graduating from the prestigious Manhattan Dalton School, and from a childhood in the privileged world of the Upper East Side, she decided “to take the first boat to Europe” instead of attending college, she wrote in her 1972 memoir “Arriving Where We Started,” “operating on the theory that to be alive and young in 1946 and 1947 meant living in postwar Europe.”

On the voyage out, accompanied by her mother, she met — in a life-altering coincidence — one Barbara Mailer, who was travelling to France to visit her older brother Norman, a young, aspiring writer who had taken an interest in Spain. In Paris, Norman convinced the two Barbaras to cross into Spain by car and spring two prisoners from a Franco jail. “As for danger or consequences,” Barbara later wrote, “life was to be led like a book; in books good people lived dangerously.”

The successful rescue mission became the centerpiece of “Arriving Where We Started,” a coming of age story described as “the best, most literary account of the intellectual resistance to Franco” when it won the Pablo Antonio de Olavide prize in Barcelona, according to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of 3as, which houses Solomon’s archives. In 2008, she was awarded the Francisco Cerecedo Prize by the Association of European Journalists in Spain, the first North American to be so honored.

In the book she also described her experiences in Germany, where she briefly lived in 1948 with her lover Paco Benet, the Spanish activist who assisted in the rescue mission. She was, she wrote, “in some inchoate way trying to figure out what had happened, and why, and who we were because of it.” She added “for a Jew to enter Germany at that time was to invite a good temporary case of paranoia.” That paranoia was, for her, especially personal. “I had always been more the child of my Prussian governess than of my mother,” she wrote, mentioning that her governess “had planned to marry an SS officer and that is hard on a Jewish child.”

Shortly after her return from Europe in 1950, Barbara enrolled in the Columbia University School of General Studies and earned a bachelor’s degree. She became part of New York’s intellectual community, writing about a wide range of topics as the American cultural correspondent for El Pais, the Spanish newspaper, and for American publications, including Dissent, Harper’s, The Nation, The New Republic and The New York Times.

Her article “I’d Rather be Dwight,” a review of critic Dwight Macdonald’s book “Against the American Grain” was published in the first issue of The New York Review of Books in 1963. Her books included the memoir “The Beat of Life,” (1960) about an unwanted pregnancy; “Horse-Trading and Ecstasy” (1989), a collection of essays; and the novel “Smart Hearts in the City” (1992), the story of an interracial love affair.

Barbara married Harold Solomon, a gifted law professor, in 1952. When he died unexpectedly in 1967, leaving her with two young daughters and little money, she realized that the women’s movement hadn’t sufficiently emphasized economic liberation. “Sexual liberation as primary goal presupposes that financial needs have been met by whom? Who meets family needs?” she wrote in her memoir “Short Flights” (1973). To make ends meet, she took a job as visiting professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo, and later taught at Sarah Lawrence and other schools.

In both her personal and professional life, Barbara looked beyond the roles that American society expected of women. In “Arriving Where We Started,” she emphasized, “I realized that as a female I was to live as I chose.” But in doing so, she could feel profoundly alone. “I couldn’t seem to find any women in the outer world or in books who resembled or answered the things I wanted answered,” she continued. “I wanted to be loved, I wanted children, I wanted adventure, freedom, security, all different ambitions juggled in my head.”

In 2000 she became the founding editor and publisher of the literary journal The Reading Room, with an advisory board included Saul Bellow, Daphne Merkin and Larry Rivers.

We often discussed literature and journalism. “I come from a very different place and time about writing than you,” she explained in an email. “More Bellowesque, more Larry Riveresque, or Rothesque. We were more free to jump around, and ignored rules about what should go here, what there.”

At her annual Christmas Eve parties, you never knew whom you might meet. There were intense discussions about art and politics.

Barbara, who usually avoided the political squabbles of intellectuals despite her focus on Nazi Germany and Franco’s Spain, described her political outlook as “non-affiliated left.” She admired Emma Goldman and James Madison. As she wrote in “Short Flights”: “Both had the good sense to mistrust organized central government.”

Warm, loving and definite in her likes and dislikes, Barbara possessed a good sense of humor and great curiosity, and she was always interested in the lives of her friends. Over the years, I relied on her wisdom about professional and personal problems. When I visited Barbara a week before her death in the East Side apartment where she had grown up, she asked several times about progress on my new film about art stolen from Jews by the Nazis. She was in good spirits and talked about her own life experiences, though she had previously told me, “I never think about my life so many years ago.”

Yet her past remained a subject she continued to ponder. In her last years, I was privileged to read a memoir she was writing, at first tentatively titled “Love in the Time of Chaos” and then “The Girl in the Green Rowboat and Other Wisps of Memory.” The memoir covered everything from the experiences of her father J. Anthony Probst during World War One in 1918 to the death of her longtime friend Norman Mailer in 2007.

In “Arriving Where We Started,” Barbara wrote, “I had largely of my own free will, entered the history of my own time.” Despite tragedy and crises, her indomitable spirit remained until the very end.