How Robbie Robertson learned he was Jewish — and the son of a gangster

The songwriter and lead guitarist for the Band died at 80

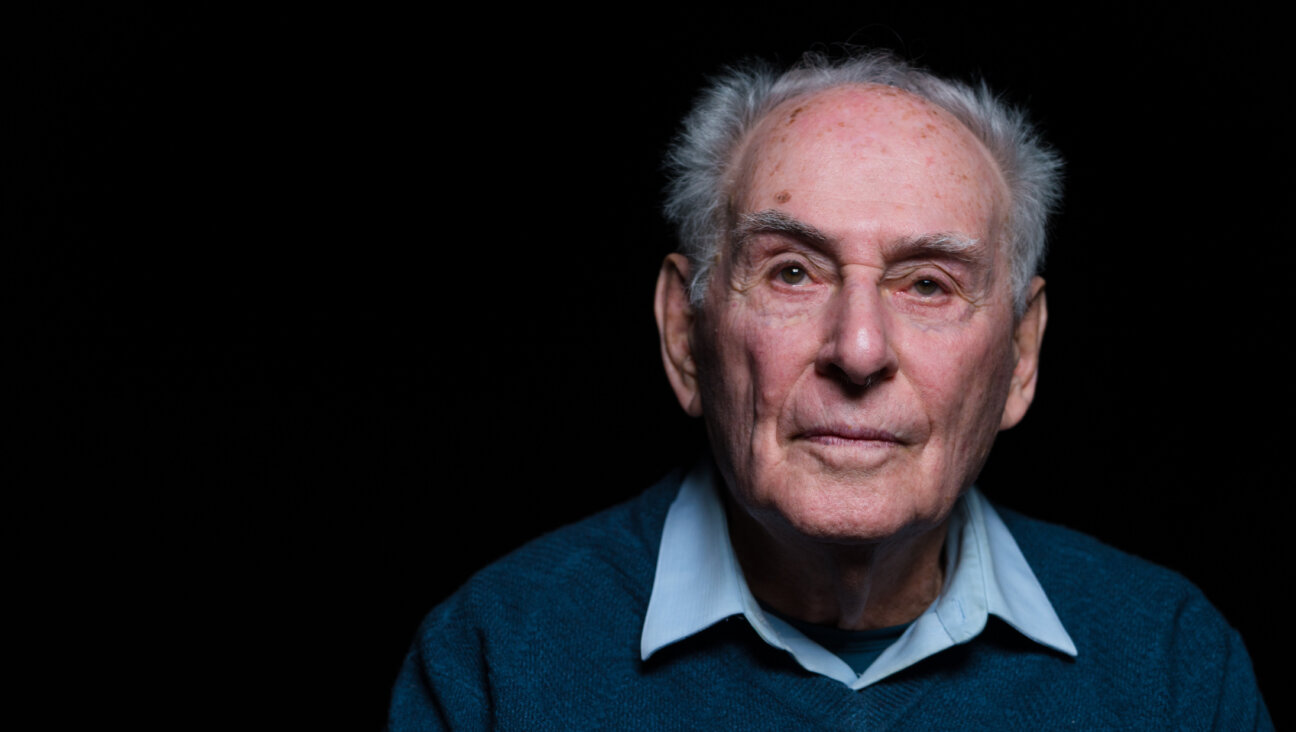

Robbie Robertson performs with The Band and Bob Dylan in 1974. Photo by Getty Images

Editor’s note: Robbie Robertson, the lead guitarist and songwriter for the Band died August 9, at the age of 80. To honor his memory, we’re republishing this piece from April 2020, about how Robertson learned of his Jewish roots.

In the new documentary film, “Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band,” Robertson – The Band’s main songwriter and guitarist – tells the story of how he finally learned of his Jewish heritage and how his Jewish relatives in Toronto embraced him and opened a whole new world of “vision” to him.

Robertson had been raised in suburban Toronto as Jaime Royal Robertson without knowing that the man he called dad, James Patrick Robertson, was not his biological father. When his mother, Dolly Robertson – who was a Mohawk raised on the Six Nations Reserve southwest of Toronto – finally had had enough of James Robertson’s physical and emotional abuse, she sat her son down, explained that she was divorcing James, and revealed to him that his natural father, Alexander Klegerman, had died in a roadside accident before Robbie was born. She also told her bar-mitzvah age son that Klegerman was Jewish.

Or, as Ronnie Hawkins, the Arkansan rockabilly bandleader who, one by one, hired the five Toronto-area musicians who would become the Hawks and later on The Band, says with a modicum of glee in the documentary, “Robbie’s real dad was a Hebrew gangster.”

Robbie picks up the story. His mother introduced him to his father’s family, including his father’s brothers, Natie and Morrie Klegerman, who were prominent members of Toronto’s Jewish underworld. “They brought me into their world with tremendous love and affection,” recounts Robertson, who would occasionally do “errands” for his uncles.

Robertson describes how the typical dream of his schoolmates was to own their own bowling alley. Having already been bitten by the rock ‘n’ roll bug, including its ethos of rebellion against the conformity of suburban life, he could not relate.

“These relatives of mine … I’m understanding what’s been stirring inside of me all this time,” he says. “They understand vision. They understand ambition. When I told the Klegermans I had musical ambitions, they were like, ‘Rock ‘n’ roll? You don’t want to be in furs and diamonds?’ And then they were like, ‘Oh, you mean show business!” That they could understand, and they even helped young Robbie, who had his own rock combo, get gigs in Toronto nightclubs.

That vision and ambition would propel Robertson through good times and bad, and he became the main engine that would drive his fellow musicians in Ronnie Hawkins’s backup band – an incredibly talented assemblage of singers and musicians including Levon Helm, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and Garth Hudson – to head out on their own, first as a white R&B group called Levon and the Hawks, then as Bob Dylan’s backup group on his controversial “going electric” world tour of 1965-1966, and later as the Woodstock-based outfit The Band, for whom Robertson wrote signature hits including “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” “The Weight,” and “Stage Fright.”

The Band built a bridge from late-1960s hippie-rock to a more soulful and cerebral 1970s roots music – what we now call “Americana.” The likes of Bruce Springsteen, Eric Clapton, George Harrison, Peter Gabriel, Van Morrison, Bob Dylan, and Taj Mahal pay tribute to the group in the film – which is now streaming on all the major rental platforms. Taj Mahal describes them as “the American Beatles”; Springsteen notes they boasted “three of the greatest white singers in rock history”; Clapton says he was “in great awe of their brotherhood.” Clapton recounts that upon hearing their debut album, “Music for Big Pink,” he broke up the English power trio Cream and traveled to Woodstock to try to get the group to hire him as a rhythm guitarist. (Needless to say, they declined, although Clapton did get all of them to play on his 1976 solo album, “No Reason to Cry,” which he recorded at The Band’s Shangri-la Studios in Malibu.)

For The Band’s penultimate studio album, 1975’s “Northern Light, Southern Cross,” Robertson wrote a song called “Rags and Bones,” which seems to pay tribute to one of the professions typically filled by Eastern European Jewish immigrants to North America – the ragman – and the sounds and music one would hear in those ghetto streets. The refrain goes:

Ragman, your song of the street/Keeps haunting my memory/Music in the air/I hear it ev’rywhere/Rags, bones and old city songs/Hear them, how they talk to me.

The Band would bow out in 1976 with the all-star concert, “The Last Waltz,” which became a live album and concert film directed by Martin Scorsese, who also appears in “Once Were Brothers.” That farewell project would cement a decades-long relationship between Scorsese and Robertson, in which Robertson would often serve as music supervisor for Scorsese’s films, as he did for last year’s “The Irishman.” Robertson would also enjoy a successful career as a critically lauded solo artist; his sixth solo album, “Sinematic,” came out last fall and included “I Hear You Paint Houses,” which served as the title track to “The Irishman,” as well as the song “Once Were Brothers,” his poignant tribute to his former Band-mates, all of whom have passed away with the exception of organist Garth Hudson.

In its loving remembrances of and tributes to his former, fallen Band-mates, “Once Were Brothers” serves as Robertson’s mourner’s kaddish for the group.

Seth Rogovoy is a contributing editor at the Forward and the author of “Bob Dylan: Prophet Mystic Poet” (Scribner, 2009).