Waters of Contention

Not long ago, I would have told you that the odds of my ever visiting a mikveh were approximately the same as those of George Bush tongue-kissing Dick Cheney. The mikveh always was an aspect of traditional Judaism I was uncomfortable with. I understand that my perspective isn’t shared by all women, and to those women who disagree with me, I say, brava to you. Dip and be well. But to me, the notion of sometimes being untouchable and sometimes being impure was distressing. (And yes, I do understand others feel that restricting touching between the sexes and marital relations at certain times is about self-control, self-discipline and turning sex into a holy act. Gotcha. No diff to me.) I also thought there was something kinky, restrictive and fetishistic about the process of determining whether you were now pure. Anne Rice, writing in her erotic, blood-obsessed porno mode, could have a field day with the mikveh.

But. There has been a movement in recent years of liberal feminists discovering the transformative powers of the mikveh, creating their own rituals. These new rituals address miscarriage, menopause, the end of chemotherapy, healing from rape, divorce… a huge variety of life transitions. Best-selling writer Anita Diamant, author of “The Red Tent,” helped found a pluralistic, nondenominational mikveh in Newton, Mass. As a former folklore and mythology major, I was fascinated by the mix of stories, prayers, poems and ceremonies on Ritualwell.org, and by those in “The Jewish Pregnancy Book” (Jewish Lights Publishing, 2003). I learned that in Jewish folklore, women in their ninth month of pregnancy are often seen as having special powers to bless other women. Some feel that if a woman who wants to get pregnant uses a mikveh after a pregnant woman, she’ll get pregnant, too.

(Like cooties, but in a good way!)

In “The Jewish Pregnancy Book,” I especially connected with an essay by Amy Friedman, who began immersing herself in the mikveh as a way of dealing with her difficulty getting pregnant. (I, too, had trouble before we had Josie.) Then, when Friedman finally did get pregnant, she went to the mikveh in her ninth month as a way to prepare to meet her baby and to pray for other women to be similarly blessed.

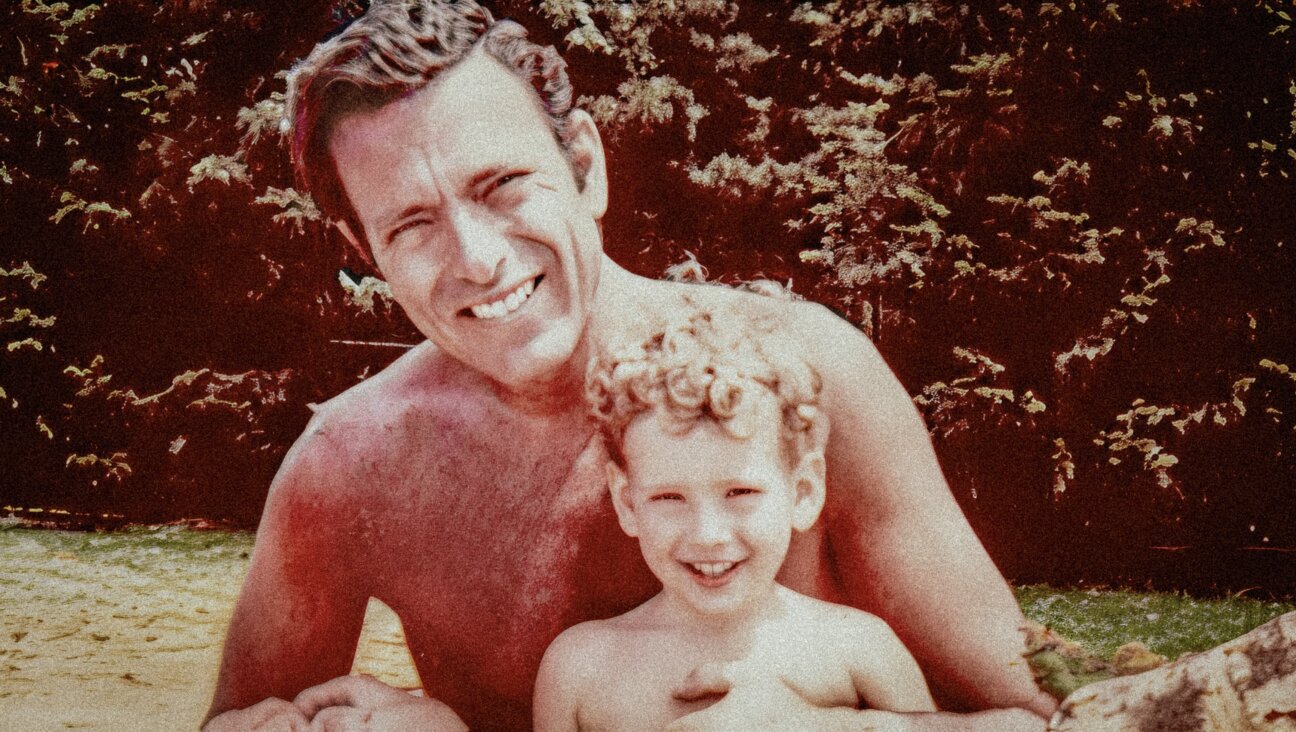

I found myself wanting to do something akin to this. My life was so busy and stressful. I worried about work, about money. For much of my pregnancy, I was focused on my father’s failing health. When I thought of the baby in my belly, I didn’t feel joy; I felt anxiety. Which was followed immediately by guilt for not being happier or more eager to meet this new person.

So the notion of communing with this baby — each of us floating in liquid, suspended, safe — was tremendously appealing. I wanted to apologize to my tiny girl for not being more present during the pregnancy. I wanted her to know I really did want to meet her and to be her mother. And I wanted to use my folkloric special woo-woo pregnant status to pray for my friends who were battling infertility.

Serendipitously, one of those friends confided that she was thinking about going to the mikveh every month. She liked the idea of ritually acknowledging her grief at not getting pregnant, getting closure on that period, putting herself in touch with the cyclic nature of her body and of time itself. She wanted to assure herself that life would go on and that she could try again. So I suggested that we undertake this journey together. We could create our own ritual. We’d each say the traditional mikveh blessing, but we’d add our own spin. I’d go in first, pray for my friends, for my baby, for myself to be a good mom to this new little girl. She’d follow, saying a prayer by Reconstructionist rabbi Nina Beth Cardin that she’d downloaded from Ritualwell.org. Then she’d drench herself in my fertility mojo. (Ew.)

But as a Reform Jew and Conservative Jew, respectively, she and I were anxious about going to an Orthodox mikveh. Okay, so I’m shallow, but I didn’t want to take out the nose ring I’ve had for a decade. (Long story. Short reason: The hole would close.) I didn’t want anyone clucking at my tattoo. I was anxious about being rushed, not feeling spiritual, not knowing what to do when everyone else did, finding myself in a dank and uninspiring place. My friend was unthrilled by the thought of being inspected for cleanliness and stray hairs by the mikveh lady.

So we went on a field trip together to the nearest Conservative mikveh, in White Plains, N.Y. It was beautiful. There were candles and lovely, brightly colored tiles. The mikveh spiraled downward like a shell, a chambered nautilus. The mikveh lady told us on the phone we could bring a boom box and music if we wanted. She didn’t give us the gimlet eye or tell us what to do, though she was delighted to answer questions and to help us clarify our intentions. I asked for help with a Hebrew word (I wanted to speak to God in Hebrew, which I think of as the language of prayer, and to talk to my baby in English). I decided to dip seven times, untraditionally, since seven is a nice mystical number in Judaism. I plunged completely beneath the surface. When I came up, I said the traditional blessing for using the mikveh. Then I said, “Shehechiyanu,” the thank-you prayer for letting me reach this special moment. Then I plunged again and again, each time davening for a different friend who was struggling to have a baby. With my remaining immersions, I talked to the baby, focusing on being loving and positive and grateful, praying for an easy delivery. I’d intended to pray for the baby’s future happiness, but in a bit of performance anxiety, I forgot. Oops. After I immersed seven times, my friend went in. She said her own private prayers. We paid our $18 and went home.

In the car, we were quiet. We both felt refreshed and a little drained. And yes, pure — the way we felt as children after a long day at the beach. Maybe it was the shock of the slightly cold water. Maybe it was the release, the exhalation of breath and anxiety after doing something so new to us. I felt more ready to give birth; she felt peaceful about a month gone, optimistic about the months to come.

I’d actually like to go back after the baby is born. Not so that I’ll be pure enough to sleep with my husband again, but so that I can say thank you, again. And I hope that soon I’ll be able to say thank you for my friends’ babies, as well.

E-mail Marjorie at mamele@ forward.com.

Shortly before press, The East Village Mamele announced the birth of Maxine Annabel Ingall Steuer (Hebrew name: Michal Aharona), 8 pounds, 1 ounce. Josie is ambivalent.

Marjorie Ingall will be on maternity leave until she is no longer hallucinating from exhaustion.