Is it time to start taking beauty pageants seriously?

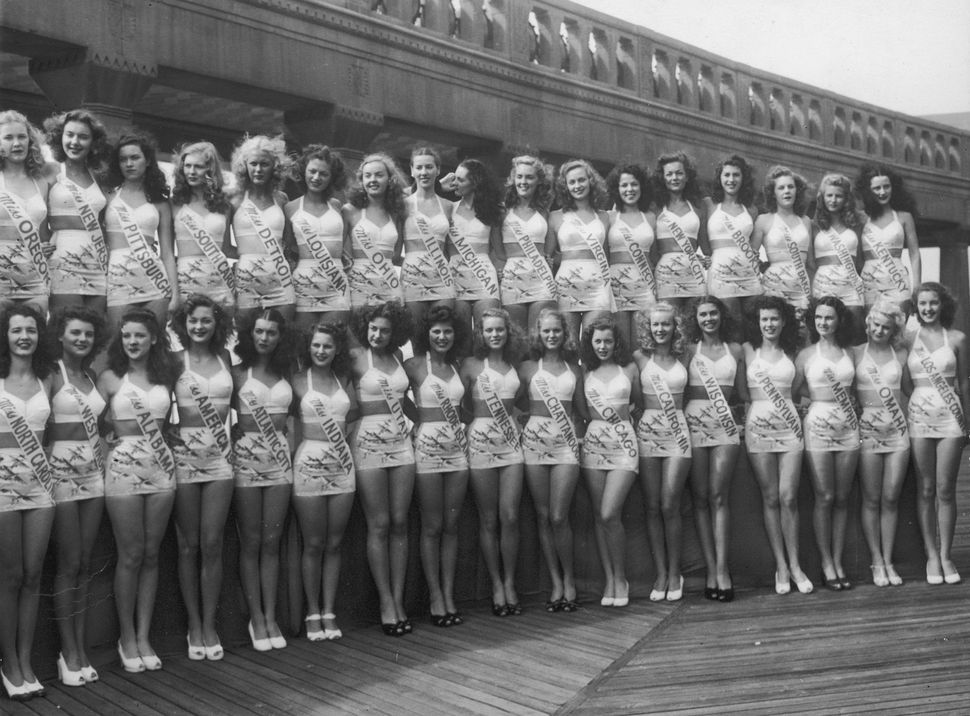

Beauty pageant, circa 1947 Image by Getty Images

Here She Is: The Complicated Reign of the Beauty Pageant in America

By Hilary Levey Friedman

Beacon Press, 256 pages, $25.95

Beauty pageants have haunted Hilary Levey Friedman since childhood. “I can’t remember ever not knowing what a beauty pageant was,” the Brown University sociologist writes in the opening pages of “Here She Is.” “In my childhood home I saw crowns on bookshelves instead of books.”

For good reason: Friedman is the daughter of Miss America 1970, Pamela Anne Eldred, to whom she dedicates the book. While her mother basked in the spotlight, Friedman writes, she stayed in the shadows, convinced that, as a potential contestant, she would never measure up. Dismissive of her own appearance, she clings to her mother’s advice: to find her own path. The irony is where that path led.

In the wake of the unsolved murder of six-year-old pageant star JonBenét Ramsey, Friedman wrote her undergraduate Harvard thesis on child beauty pageants. At Brown, she teaches a seminar titled, “Beauty Pageants in American Society.” One of her students, North Dakota’s Cara Mund, became Miss America 2018. Friedman, though she herself never competed, judges pageants – and is also president of the Rhode Island chapter of the National Organization for Women.

“Here She Is” braids together those seemingly contradictory strands, mapping the evolution of beauty pageants onto the arc of American feminism. Combining history, sociology, journalism and memoir, the book offers a provocative, sometimes sprawling overview that Friedman describes, accurately, as “neither an indictment of beauty pageants, nor a paean….”

Friedman agrees with feminist criticisms that see beauty pageants as vehicles for the objectification of women, while noting that looks do contribute to success in life, and that many pageant judges are female. She also details pageants’ racist, ableist, homophobic and otherwise exclusionary history, and their role in the policing of women’s sexuality.

One case in point is the first Black contestant to be crowned Miss America, Vanessa Williams, dethroned in 1984 because Penthouse magazine published nude photos of her with another woman. The pageant apologized decades later, while Williams transcended the setback and established a major career as a singer and actress.

But Friedman doesn’t linger on embarrassments and missteps. She mostly gives pageants the benefit of the doubt, touting them as sources of scholarship money, valuable skills training, and platforms for professional success, as well as sheer fun.

She insists that we have much to learn by looking at pageants in a new, and more forgiving, light. “In reality,” she writes, “the history of pageants mirrors the many monumental changes related to a woman’s place in society, while still showing how far we have to go in our expectations of and for women and girls.”

As for “Miss America,” she writes, it is “possibly the best example of the difficult and complicated nature of American womanhood,” morphing through the years to reflect women’s educational and professional attainments. Despite being increasingly embattled and itinerant, the pageant, shorn of both its controversial swimsuit component and evening-gown competition, remains, for Friedman, “the gold standard.”

“Miss America” and “Miss USA/Miss Universe” (once owned by Donald Trump) constitute what we might call Big Pageantry. But Friedman reminds us that a raft of industry-specific, festival-based, ethnic, and other pageants also exist, for “Native American girls, married women, teenagers in wheelchairs, drag queens, petite females, and much more.”

Still, she acknowledges, “While there is a diversity of pageants, there is little diversity within pageants. Most pageants favor women who display thin, fit, and able bodies, light skin, and long hair. The assumption is that most pageant contestants are heterosexual, Christian, and middle class.” In its century or so of existence, “Miss America” has crowned only one Jewish woman, Bess Myerson, who won the title in 1945 and encountered anti-Semitic slurs.

Friedman unearths some unexpected connections between pageantry and feminism. She notes that, in the 19th century, women were mostly relegated to the domestic sphere, making even pageantry verboten. The suffragists helped enlarge women’s public profile, Friedman says, even if their intent was never to make the world safe for bathing beauty contests. They also bequeathed contestants the sash, a fixture of suffragist garb that was borrowed from the military. The early “Miss America” pageants, in the 1920s, had a distinctly reactionary cast. “As women began to be subjects with voices,” Friedman writes, “they were put on a pedestal as silent objects.”

The relationship between Second Wave feminism and pageantry was often contentious. Women’s liberation groups piggybacked on “Miss America” in 1968 to attract media attention to their demands. (“Miss Black America” launched that year as well.) Protests culminated in the infamous “bra burning” demonstration, in which bras were trashed but not actually burned. A group called New York Radical Women briefly disrupted the pageant itself. One of its leaders, Robin Morgan, had been a child beauty pageant contestant. (Even Gloria Steinem had pageant experience, Friedman notes.)

Identity politics in the 1980s and ’90s helped reshape pageantry, Friedman writes, “as more specific pageants developed to elevate an increasing variety of feminine ideals….” Departing from other scholars, Friedman doesn’t date Third Wave feminism to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’s 1991 Senate confirmation hearing, during which Anita Hill alleged that Thomas had sexually harassed her. Friedman links it instead to the Trump era, which has spawned massive women’s marches and the #MeToo movement. And she credits this latest iteration of feminism with the elimination of the “Miss America” swimsuit competition.

Even as pageants themselves struggle, Friedman suggests that pageantry has infiltrated reality television. One obvious example is “The Bachelor” franchise, whose creator, Mike Fleiss, judged the “Miss America 2012” pageant and later married that year’s winner. On “The Bachelor,” the women “wear evening gowns, don bathing suits, and attempt to show off a talent,” Friedman writes. The host, Chris Harrison, was also a longtime “Miss America” host. By incorporating episodic drama, shows like “The Bachelor” ratchet up audience involvement, doing pageants one better.

Of course, beauty pageants themselves are “full of backstage drama,” Friedman writes, even if she’s not interested in supplying “insider snark and innuendo.” She would far rather that we take pageants seriously – maybe more so than most of us would prefer.

Julia M. Klein, the Forward’s contributing book critic, has been a two-time finalist for the National Book Critics Circle’s Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing. When she was five, she thought it would be fun to be Miss America. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaMKlein