So, what did Agatha Christie really think of Jews?

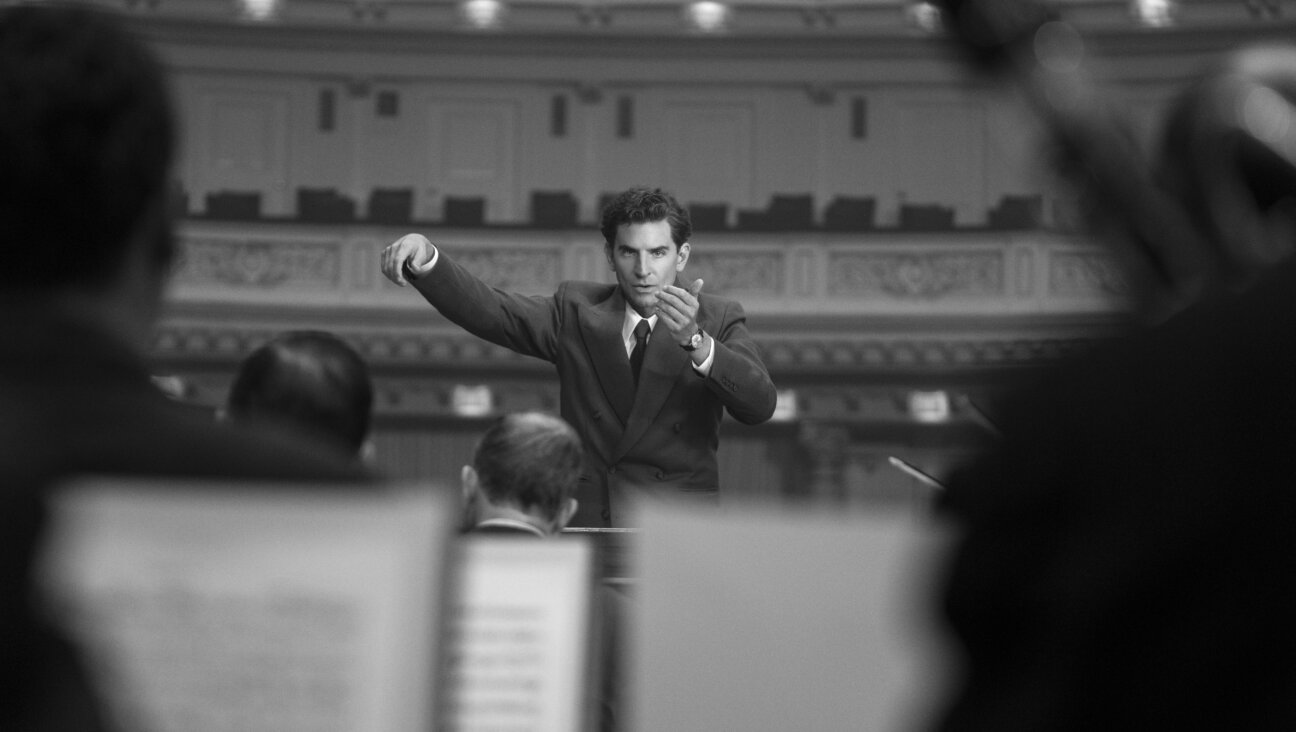

Agatha Christie Image by Getty Images

With “Death on the Nile,” Kenneth Branagh’s latest film adaptation of Agatha Christie’s detective Hercule Poirot tales due for release in December, along with a new book-length study of Poirot, who is celebrating the centenary of his creation, it’s a moment to recall just how antisemitic the early detective novels of Agatha Christie were.

“The Guinness Book of World Records” lists Christie as the best-selling fiction writer of all time, with her 66 detective novels having sold about two billion copies internationally.

Many of Christie’s ardent fans have been Jewish. The actor Harold Huber impressed 1940s radio audiences with a series of performances as Hercule Poirot. “The Palgrave Dictionary of Anglo-Jewish History” points out that among the scriptwriters for the ITV series of adaptations of the Poirot stories is Anthony Horowitz. Another whodunit maven, Lev Raphael, is listed in “Contemporary Jewish-American Novelists” as being influenced by her precedent.

Even the world of Jewish historical scholarship has been inspired by Poirot’s delving into the past to find solutions. In “Jewish Dogs: An Image and Its Interpreters” Kenneth Stow introduced a new interpretation of Hebrew texts this way:

“An analogy to the modus operandi of Hercule Poirot may not be out of place – pale as my skills at detection may be by contrast to those of Agatha Christie’s master sleuth, not to mention to Agatha Christie’s mastery of the written word: first the long build-up, the problems carefully arrayed, then Poirot confronting the assembled suspects and meticulously sorting out the clues.”

Similarly, in “Jewish Women Philosophers of First-Century Alexandria,” Joan Taylor, a historian of religions, wrote:

“When Christie’s Hercule Poirot sets out his case in front of a tense audience of suspects, someone generally confesses to clinch the accuracy of his cool reconstruction of events. In the case of a scholarly investigation of the past, especially of this nature, we do not have this confirmation after our sleuthing.”

Sometimes historical Jews have even been retrospectively assimilated to Christie’s Belgian detective, as when the biographer Jane Ridley referred to 19th century philanthropist Baron Maurice de Hirsch’s “waxed Hercule Poirot-like mustaches.”

While Christie’s novels are a mechaya for researchers thinking about Yiddishkeit, some previously published content, long suppressed in the USA, might cause eyebrows to be raised today.

After World War II, Christie’s literary agent authorized her US publisher to silently delete anti-Semitic references in reprints of her pre-war novels. This effort at retrospective image-polishing was not done in her native England. Thenceforth, American readers have had an edulcorated view of just how anti-Semitic Christie’s earlier books were.

For some Christie fans, the subject remains taboo. The upcoming “Agatha Christie’s Poirot” (William Morrow) by UK television historian and Christie superfan Mark Aldridge does not mention anti-Semitism.

But then, the matter has been investigated elsewhere. In “Challenges in Jewish-Christian Relations” the religious historian Martin Forward wrote of “reflex antisemitism” among 20th century popular writers in Great Britain: “A particularly noteworthy example of such unthinking prejudice is Agatha Christie, the so-called Queen of Crime.”

Forward cited the novel “Three Act Tragedy” (1935) a Poirot mystery in which “barbed language about Jews appears,” in addition to “many more of her works…The point is not that [Christie] was a particularly virulent exponent of anti-Jewishness or even consciously anti-Jewish. Worse in a way, her casual comments illustrate the stereotypes and caricatures widespread in British society of her day.”

As alert to current trends as her brilliant Belgian detective Poirot, Christie would insert allusions to Jewish history into her narratives. Political scientist Stephen Bronner has noted that in another Poirot novel, “The Big Four” (1927) Christie made a satirical reference to “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” a fabricated anti-Semitic text about a supposed Jewish plan for world domination, by alluding to a conspiracy text entitled “The Hidden Hand in China.”

Christie specialist Gillian Gill was unequivocal:

“A kind of jingoistic, knee-jerk anti-Semitism colors the presentation of Jewish characters in many of her early novels, and Christie reveals herself to be as unreflective and conventional as the majority of her compatriots… Christie’s anti-Semitism had always been of the stupidly unthinking rather than the deliberately vicious kind. As her circle of acquaintances widened and she grew to understand what Nazism really meant for Jewish people, Christie abandoned her knee-jerk anti-Semitism. What is more, even at her most thoughtless and prejudiced, Christie saw Jews as different, alien, and un-English, rather than as depraved or dangerous – people one does not know rather than people one fears.”

An article by Jane Arnold in “Jewish Social Studies” from 1987 concurred, documenting 23 Christie narratives in which Jews appear. Their names include Herman Isaacstein,, a businessman; Isaac Pointz, a diamond dealer; and Sir Reuben Rosenthal, an art collector.

The men and women are sometimes described as physically alluring, but more often as ugly, with facial features confirming typical racist expectations. As the critic Robert Barnard indicated, in Christie’s early novels, “one can be fairly sure that any Jewish character will be ridiculed, abused or rendered sinister.” Even in 1932, in “Peril at End House” (1932) a prosperous art dealer named Jim Lazarus is referred to by one speaker: “He’s a Jew, of course, but a frightfully decent one.”

“Victims or Villains: Jewish Images in Classic English Detective Fiction” concludes that although most comments about Jews in Christie’s works are as offensive as the usual low standard of Golden Age British detective novels, “[Christie] could, and did, confound reader expectations with more sensitive allusions at times.”

Jane Arnold likewise observed that in Christie’s writings, “No particular Jewish characteristic is completely negative.” This ambiguity may have been due in part to an incident recounted in Christie’s autobiography. In 1933, she accompanied her husband, an archaeologist, to the Middle East for an excavation. There they met Julius Jordan, Germany’s Director of Antiquities in Baghdad. When someone mentioned Jews, Jordan retorted: “Our [German] Jews are perhaps different from yours. They are a danger. They should be exterminated. Nothing else will really do but that.”

Christie’s reaction was to stare at Jordan “unbelievingly” and observe to herself: “There are things in life that make one truly sad when one can make oneself believe them.” The UK National Archives website further explains that Julius Jordan was Nazi Party leader and propaganda director for Iraq. So Christie had encountered the local equivalent of Joseph Goebbels.

To her credit, this meeting and the ensuing war eventually led Christie to change her previous habit of including dubious Jewish characters in her books, although offensively crypto-Jews continued to appear until 1950, when a refugee cook named Mitzi was mocked for her persecution complex in “A Murder is Announced.”

What Christie felt personally remains a moot subject. Christopher Hitchens, the English journalist of Jewish origin, recalled that when he dined with Christie and her husband in the 1960s, the “anti-Jewish flavor of the talk was not to be ignored or overlooked, or put down to heavy humor or generational prejudice. It was vividly unpleasant.”

Yet for most American Jewish readers, especially of expurgated US editions of her classic titles, Christie remains a recreational delight.