Her Holocaust survival story was like something out of a Netflix movie — maybe too much so

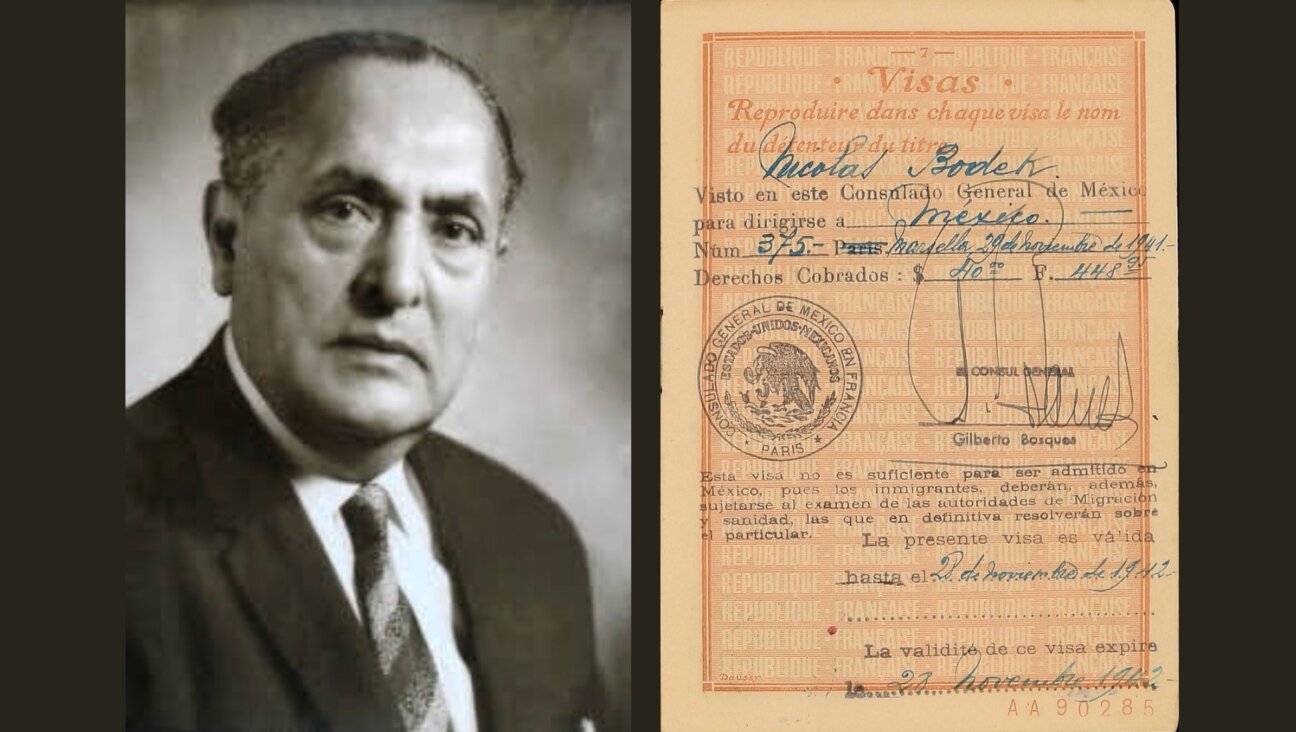

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Misha Defonseca had a secret. As she stood before the synagogue at Temple Beth Torah in Holliston, Massachusetts, she harbored a tale so remarkable that it would eventually catapult her to international notoriety. After a half century of silence, Misha began to share her story of escaping Nazi-occupied Belgium during the Holocaust. Her fellow congregants were stunned to learn the details of her journey.

The story began with Misha’s parents’ disappearance, after which she was “hidden” by a Catholic family who raised her. Determined to find her parents, she ran away, walking east across Europe, living mostly in the forest, subsisting on bugs, avoiding Nazis in the Warsaw Ghetto, and even stabbing one to death in self-defense. Astonishingly, she gained the trust of a pack of wolves, living among them for months and sharing in their kills.

She eventually returned home after the war, married, and decades later moved with her husband, Maurice, and son to Millis, Massachusetts outside Boston in 1988 where her husband had been transferred to work with a computer firm. A local publisher, Jane Daniel of Mt. Ivy Press, heard Misha’s story and convinced her to write a memoir, sensing a bestseller would boost Daniel’s own fledging publishing business. The book, “Misha: A Mémoire of the Holocaust Years,” was published in 1997 and garnered widespread excitement. It was translated into 18 languages, Disney optioned the film rights, a French film was made, and even Oprah invited her to her book club.

Literary Mystery: The saga of an alleged Holocaust survivor is the subject of Sam Hobkinson’s film ‘Misha and the Wolves.’ By Misha and the Wolves

Misha inexplicably refused to accept Oprah’s invitation to be on her show, rebuffing exposure that would have ensured the book would become a hit. Instead, Misha sued her publisher Jane Daniel for stealing the copyright and withholding royalties from the book which Daniel held in an offshore account. In the resulting trial, the jury sided with the wronged Holocaust survivor, leaving Daniel ruined and disgraced.

As Daniel tried to figure out where things went so wrong, she came across a bank slip in Misha’s handwriting with Misha’s mother’s maiden name and place and date of birth, something Misha had said had been lost in the war. Pulling this one string began to unravel Misha’s carefully woven tapestry and revealed a surprising wealth of truth and deceptions about what really occurred.

Misha Defonseca’s story is now the subject of “Misha and the Wolves,” an enthralling new Netflix documentary that is part Holocaust survival story and part crime drama with all the twists and reveals of a great mystery. The film, directed by British director Sam Hobkinson (“Fear City,” “The Hunt for the Boston Bombers”), recounts Misha’s story, the publication of her book, and the subsequent fallout, some details of which may be familiar to readers.

Lupine History: ‘Misha and the Wolves’ is an enthralling documentary that is part Holocaust survival story and part crime drama with all the twists and reveals of a great mystery. By Misha and the Wolves

Hobkinson discovered Misha’s story six years ago in a small UK newspaper article about her suing her publisher. “I wasn’t looking for a Holocaust documentary to make,” Hobkinson said, “it started as a history documentary and became a psychological thriller. Halfway through, I realized I was making a post-modern Holocaust documentary. I wasn’t making a film that was about the terrible events themselves, but about everything that has come after them.”

As Hobkinson learned all the details of Misha’s story (which I am purposely leaving out so viewers can enjoy the delicious reveals of the film and avoid spoilers) he knew he had much more than another tale of survival. Instead he crafted “a story about storytelling,” he said. “It’s about the process of documentary making, finding a true story and making a story about that. I’m fascinated in what makes us believe stories to be true.”

Hobkinson masterfully lures in the audience and provides an early twist worthy of M. Night Shyamalan. “I wanted it to be an immersive film,” he said. “I wanted it to play and feel like a drama movie in a way, to be experiential, to feel when it twists and turns. So we found ways of doing that.”

It was important for Hobkinson that the film not present this story as a cut-and-dried case. Both Misha and Daniel are, in a sense, wolves, at once perpetrators and victims. “It’s important for the viewer to leave the film and have an opinion one way or another,” he said, “I didn’t want to give them an opinion. And I hope people will leave the cinema and argue about it. Because I think it’s worth arguing about.”

One of the film’s true heroes is Evelyne Haendel, who was also a hidden child in Belgium during the war and later learned the troubling true story of her own upbringing. Haendel, who became a sort of Holocaust survivor detective, helped uncover the truth about Misha’s past. Hobkinson calls her the “film’s center of good…the one person with no ulterior motive”; he gave her the film’s impactful last words.

A larger question the film raises is why people believed Misha’s fantastical story in the first place and why they were reluctant to challenge it. And, further, once the deception was revealed, will bringing more attention to it empower those who believe the Holocaust is “fake news”?

“I actually believe this is a film that should be made so it can claim the story back from the Holocaust deniers,” Hobkinson said. “We made a film about how and why we believe things to be true. The concept of truth is a slippery one.”