How did Bob Dole get along with the Jews? It’s complicated.

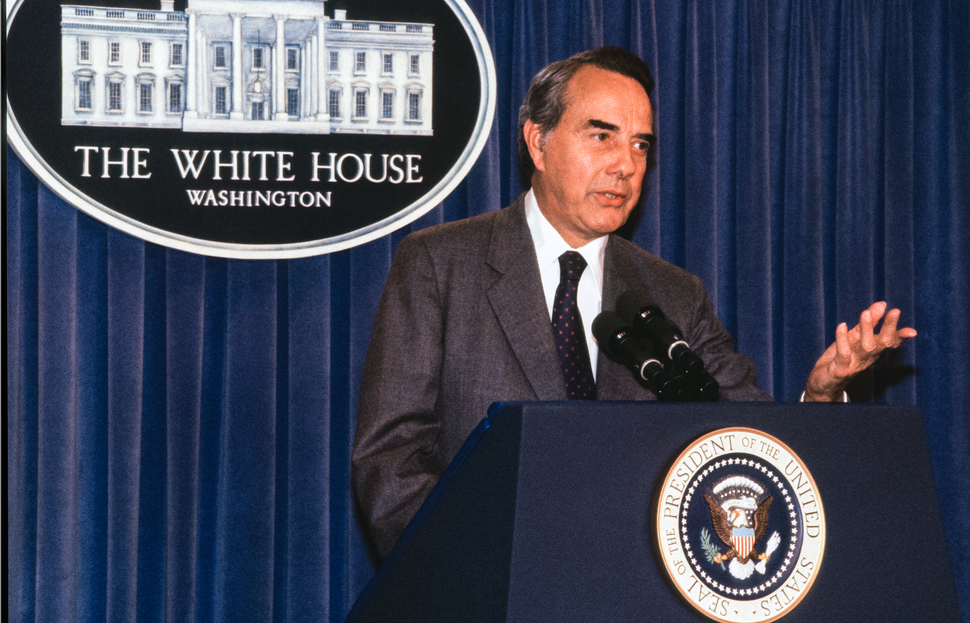

Bob Dole By Getty Images

To understand the rapport with Jews and Jewish history of Senator Bob Dole of Kansas, who has died at the age of 98, a surprising number of analyses of jokes are required, worthy of the precedent of Sigmund Freud.

In addition to a distinguished legislative career and splendid military record, Dole cultivated the reputation as a cracker-barrel jester. He published collections of wry anecdotes about politics and presidents.

So as the Chicago Tribune reported in May 1990, when an uproar ensued after Dole recommended that the U.S. should reconsider lending Israel $400 million to shelter Soviet Jewish refugees, he claimed that he was “kidding.”

The presumed levity was over whether Dole would “split (the $400 million) between homeless, disabled American veterans and Israel. Within an hour, there was a call from the Israeli Embassy to Sen. [Warren] Rudman, who called me and said, (here Dole’s voice rose in mock alarm) ‘Are you going to offer this amendment?’”

The Tribune suggested that Dole’s habit of blurting out comments, belatedly identified as jokes, may have been due to “boredom” after decades in the Senate.

Dole could seriously appreciate Jewish political allies like the Republican activist Esther Levens. In August 2020, when Levens, founder of the Kansas-based Unity Coalition for Israel, died, Dole’s Twitter account acknowledged the news with a tweet of sympathy, albeit spelling her name wrong as “Levins.”

Jewish voters were likewise treated to declarations of support for Israel by Dole, studded with speechwriters’ attempts at Hebrew transliteration. In the Dole Archive at the University of Kansas is a discourse from October 1978, labelled that the listeners were JEWISH RETIREES—RESIDENTS OF CENTURY VILLAGE; TEMPLE ISRAEL; DEERFIELD BEACH, FLORIDA.

The speechwriter ambitiously expected Dole to pronounce the Hebrew phrase Lo Teduu od milchama. (They shall never again know war; Isaiah 2:4) among other Hebrew words, possibly to convince Temple Beth Israel’s faithful that Dole was a landsman, not a Methodist from the prairie.

Unlike these serious public references to Jewish subjects, with Jewish politicians in private, Dole could be teasingly caustic.

Senator Joe Lieberman’s book on the beauty of Shabbat, includes rationalization of Lieberman’s failing to keep the Sabbath in January 1991 in order to vote in favor of the First Gulf War. After the measure passed, Dole handed Lieberman a telephone and insisted that he speak to President George H.W. Bush. Yet Dole probably knew that for Orthodox Jews, phone conversations on Shabbat are a no-no.

In a 2007 interview, the American Jewish politician Dan Glickman noted that Dole “had this kind of harsh personality, some people thought, you know, the biting, cutting-edge humor and everything else, which I think he did at times have, but I never found him vindictive.”

However, Glickman was taken aback when circa 1986, he mulled over the possibility of running against Dole. One day, his office was visited by representatives of the America-Israel Public Affairs Committee. The group, including some friends, admonished him not to oppose Dole, that loyal supporter of Israel. Glickman reflected, “Whether Dole sent them to do that or whether they just did this on their own, I don’t know.”

Dole’s use of “cutting-edge humor” in the context of politics and things Jewish could even extend to solemn occasions. In March 2000, as part of a formal presentation in the Leader’s Lecture Series of the US Senate, Dole made straight-faced statements, including his opinion that Strom Thurmond, the South Carolina Dixiecrat senator, was a “giant.”

Then Dole proceeded to insert a Jewish joke, claiming that “as a weapon against injustice, ridicule can be as effective as moral outrage.” The jape was attributed to Arizona senator Barry Goldwater: “On being blackballed by an anti-Semitic country club in Phoenix, Goldwater responded: ‘Since I’m only half Jewish, can I join if I only play nine holes?’”

Although cited in books about Goldwater,, including even a well-researched biography, this wisecrack appears to be a variant of another gag supposedly uttered by Groucho Marx. As the tale goes, when an anti-Semitic country club banned Groucho from swimming in its pool, he replied by asking if his half-Jewish daughter (or son, depending on the narrator) could wade in up to her/his knees.

Unfortunately, attempts at humor involving Jews by Dole’s political cronies could get him into hot water. One example was in May 1995, when Ed Rollins, a Republican political consultant to Dole’s Presidential campaign, thought it appropriate to refer to US Representatives Howard Berman and Henry Waxman, both California Democrats, as “Hymie boys.”

The occasion was a roast for Willie Brown, an African American speaker of the California State Assembly, who planned to run for mayor of Los Angeles. Rollins declared, “If elected mayor of L.A., [Brown] could show those Hymie boys, Berman and Waxman, who were always trying to make Willie feel inferior for not being Jewish.”

The Dole campaign’s reiterated response to the ensuing furor was that it would “stand by” Rollins, although the political consultant himself, seeing that the outcry did not diminish with time, eventually chose to resign as senior adviser to Dole’s presidential effort.

In another glimpse at Dole’s apparent tolerance of antisemitism among colleagues, his close ally Carroll Campbell, governor of South Carolina, whom Dole considered as a vice presidential running mate, raised hackles by commissioning a poll in 1978 that highlighted his Democratic opponent’s Jewish roots and beliefs.

Greenville Mayor Max Heller, an Austrian-born Jewish refugee, was targeted by Campbell with a poll that queried voters about how they felt that Heller was “(1) a Jew; (2) a foreign-born Jew; and (3) a foreign-born Jew who did not believe in Jesus Christ as the Savior.”

Dole’s criteria of acceptability for jokes, or even serious statements, about Jews could be mystifying. In October 1996, Dole told the international convention of B’nai B’rith, without a hint of humor, that physical disabilities he acquired from valiant military service in World War II gave him affinities to Jews. This implied, whether intentionally or not, that Jews are innately disabled.

B’nai B’rith president Tommy Baer tactfully demurred that being Jewish was not inherently a disability, while the theologian Michael Berenbaum told “The New York Times”: “Most Jews today don’t regard being Jewish as a handicap. They regard it as a privilege; it gives them roots and depth and a mission.”

In his own mercurial way, Dole was capable of speaking to a rally demanding that the Soviet Union allow an ailing Jewish scientist, Benjamin Charney, to emigrate. Yet Dole refrained from signing a Senate petition in 1987 requesting Charney’s liberation, possibly because it was sponsored, and mostly signed, by Democrats.

In June 1995, Stanley Hilton, Dole’s former aide and Senate counsel, published a book, generally dismissed as an unflattering portrait. Hilton claimed that Dole “sometimes privately expressed envy and resentment at Jews for having an unduly large amount of money, power and influence in the United States, and for bankrolling liberal Democrats’ campaigns.”

Perhaps ultimately, as a true politician, the most essential thing for Dole about Jews or anyone else, was partisan electoral support to maintain power.