How a Holocaust survivor thrived in an art world that didn’t want her

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Against all odds, Mila Gokhman has made a life full of flowers.

“The main things in my life are flowers and trees,” the artist, 87, said in an interview. She was speaking from Los Angeles, where she lives today. But we were talking about an artistic journey that took place in another country entirely.

Mila Gokhman wearing one of her own creations. Image by Michele Mattei

Born in Kyiv, Ukraine in 1934, Gokhman survived the Holocaust by hiding with her family in the Ural Mountains. Returning to her native city after World War II, Gokhman found that under the new Soviet regime, her religion limited her opportunities. Officially, she trained as an engineer. Unofficially, she cultivated her skills as an artist, creating elaborate flower arrangements and installations with materials harvested from the forests outside Kyiv, terrain that had been the site of so much bloodshed during the war.

Entrenched antisemitism, Gokhman said, made it nearly impossible for her to enter the established art world. However, she was active in Kyiv’s bohemian underground and eventually gained widespread recognition in her home country — not just for her flower arrangements but for leather reliefs, jewelry and paper collages, many of which drew on the natural motifs that first inspired her.

In 2000, Gokhman immigrated to California, where she started anew as an artist working in obscurity. But even while struggling to gain recognition — and, most recently, to make it through the coronavirus pandemic — she’s continued to create, filling her home with piece after piece. “The accumulated energy of her lifetime of work pulsates against the walls of her tiny apartment, waiting to be loosed upon the world,” wrote Roni Feinstein, an art historian who met Gokhman through her local Jewish Federation and made it her mission to bring public attention to her work.

Or as Gokhman, who is already drawing up schematics for a post-pandemic exhibition, put it: “Huge numbers of my work are waiting to be seen.”

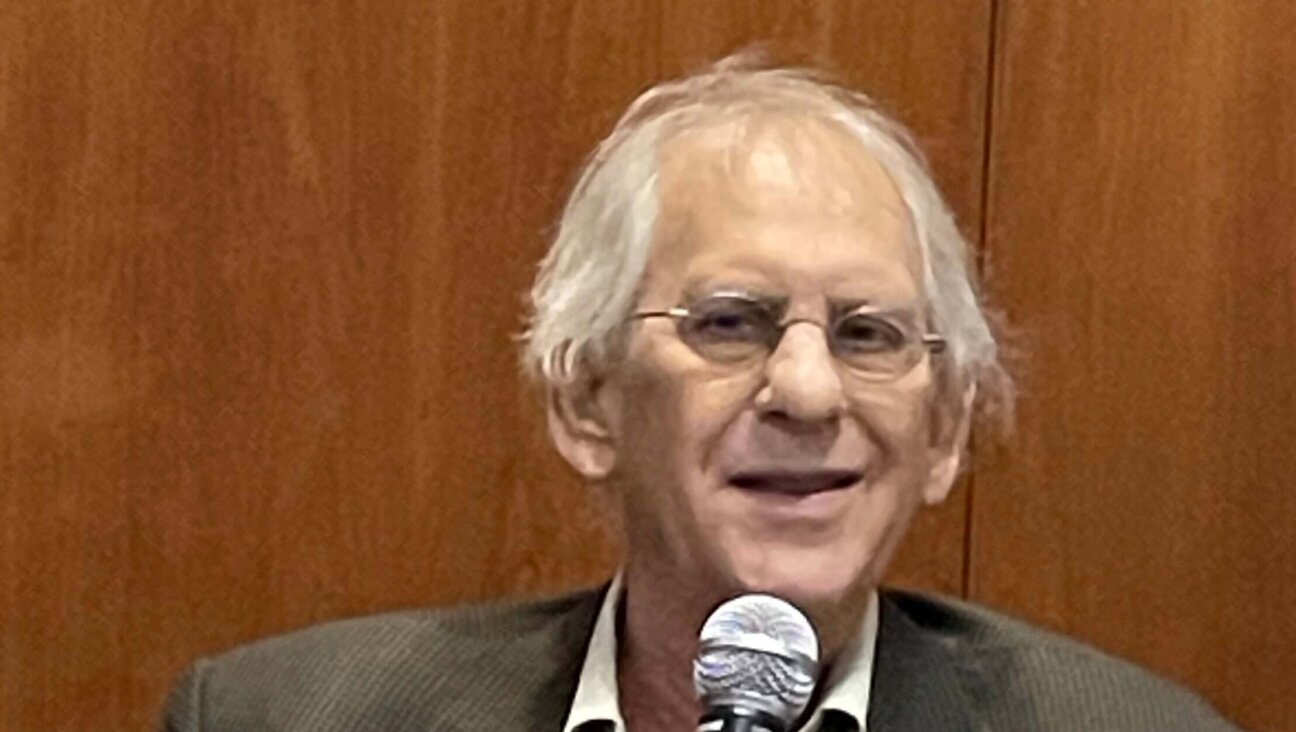

Gokhman speaking to a reporter at the opening of her 1981 exhibition at St. Petersburg’s Yegalin Palace, “Plasticity and Color.” Image by Courtesy of Mila Gokhman

In Her Words

“I was working as an engineer and I hated it. In the morning, when it was sunrise, I was in the forest. All the time I was free, I was in the forest. In the markets, I was buying flowers. Flowers were the main thing in my life. Sometimes for the whole night, after going to the forest and before work, I was doing arrangements.”

“The Note of Silence, Memory,” paper collage, 2020. Image by Mila Gokhman

“By chance I was at my friend’s in Estonia, and it happened that I was invited by a lady who worked in a plant making leather book covers. I had left my engineering half a year before, and I was trying to find myself. I saw on her wall some pictures made from leather. She said, ‘You are an artist, you can do something for yourself,’ and presented me with a sack of leather strips and glue. And I came home and found some cardboard to see what I could do. That was my artistic birthday. After that, I never stopped working with leather.”

“Golden Rain,” leather and leather dyes, 1973. Image by Mila Gokhman

“Composition with Red Flower,” leather and suede. Image by Mila Gokhman

“In the beginning of the 1980s, there was a show in Moscow of Yves Saint Laurent, the designer. At the time I was known as a leather artist: I was working with the best fashion house in Kiev, making belts, purses, pendants. My friend, who was one of the editors of a Russian magazine, wanted to introduce me to Yves Saint Laurent, so I sat down and made some pieces. It didn’t happen — my parents were ill, and I was not able to go to Moscow. But that friend brought a photographer to my house in Kyiv, and I invited a girl from the flower shop to help me, and they made that picture. That girl is not a model, but I think it’s the best photograph of my leather jewelry.”

Leather body ornament, 1991.

Gokhman designed this coat with leather details for the Kiev Fashion House. Image by Courtesy of Mila Gokhman

“When I was living in Kyiv I was concentrating on what I was doing so deeply, so intensely, that I was not able to listen to anything. Here, I listen to music, but I hear very badly. It’s like some shadow, somewhere, but it’s a good shadow.”

“Ballet,” paper collage, 1988. This piece is dedicated to the Russian choreographer Boris Eiphman. Image by Mila Gokhman

“Improvisation, Part I,” paper collage, 1991. Image by Mila Gokhman

“I have many health problems, but when I have some work I get up early and run to my table and sit there. The only medicine for me is to sit at the table and make my collages. I made this new series after a Russian children’s song, which sounds like this — Let the sun be forever, let my mother be forever, let me be forever — in opposition to the COVID situation. I couldn’t stop doing these lines, bright yellow rays and shadows. I love shadows as a subject for life.”

“Asymmetrical Symmetry,” cut and pasted wallpaper samples, 2019. Image by Mila Gokhman

An untitled piece from Gokhman’s “Sun Rays and Hope” series, created during the pandemic. Image by Mila Gokhman