Ed Asner’s very righteous (and very Jewish) journey

Ed Asner By Getty Images

The American actor Ed Asner, who died on Aug. 29 at age 91, showed that Jewish identity can mean defending a range of minority groups, not just fellow Jews.

Asner had little opportunity to express this viewpoint as the editor Lou Grant on “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” a character he described to Jewish journalist Lionel Rolfe as “theoretically Catholic” although Asner “always thought he had the map of Israel written all over his face.”

More explicit issues related to Yiddishkeit were explored in the grittier spinoff “Lou Grant,” particularly the episode “Nazis” in which a so-called National Socialist Aryan American political party in Los Angeles is led by a Jewish-born miscreant whose father explains that he “said Kaddish for” his son “years ago.”

Epitomizing Asner’s approach to acting as a humanistic investigation, his character informs a reporter that the real story is not about exposing the neo-Nazi’s origins, but to address the question of “what turned this bar mitzvah boy into a Nazi with a swastika on his arm – how did it happen?”

Asner understood this, as his choice of acting career stemmed from his own bar mitzvah experience.

He was born in Kansas City, Missouri, raised in an Orthodox working class family in Kansas City, Kan., by a Lithuanian father and a mother with the “darkness and the gypsy-like quality of the Jews of Odessa,” as he told an interviewer from the Yiddish Book Center (YBC) in April 2018.

Frayed nerves ruined his Haftorah reading during his bar mitzvah. The post-ceremony “stigma was intense…but I think it probably turned me into an actor…Having failed my first performance, I was determined to make better. I guess I’m still trying.”

As a boy in Kansas City, Asner learned watchful reticence about Judaism. Classmates used such expressions as “He jewed me down,” but this bigotry paled beside the violence meted out against African-Americans and Mexicans. Two of his sisters were social workers, adding to his public-spirited awareness.

Placing the condition of the Jews in a wider context became an early habit. He reveled in what he called the “grandiosity of Judaism… the bigger-than-life heroes, the drama of Judaism,” as he explained to the YBC. Yet he retained from the language of the Ashkenazim naughty epithets which he delighted in exclaiming even in old age, such as kurveh (whore) and nafkeh (streetwalker).

Feeling guilt about not volunteering to defend the Jewish state during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, he later became a sometimes perplexed observer of the Middle East, informing the YBC that “interestingly enough, there came a time where Hebrew was so emphasized in Israel that Yiddish was falling by the wayside. And the homosexuals, who were rejected in Israel at that time, anyway, were turning to Yiddish more and more because Hebrew wasn’t accepting them or they weren’t finding acceptance with Hebrew. So, mame-loshn (mother tongue) became the homosexual shprakh (language).”

More than just an idle observer to presumed homophobia, in 1977 Asner vocally opposed the repeal of an anti-discrimination statute in Miami’s Dade County. He filmed a public service announcement contradicting the claim by Anita Bryant’s Save Our Children organization that LGBT Americans were a societal threat. Asner explained:

“I’m not a homosexual, but I’m concerned about the rights of all people. Rights are important to me as a Jewish person. I believe it’s wrong to deny anyone the right to work or the right to live where they want because of their religion their race, or their sexual preferences. Where does bigotry stop? As a Jew, I can’t forget that once in this world it didn’t stop. That’s why it’s imperative that June 7 you vote against repeal of homosexual rights in Dade County.”

His willingness to defend others was especially noteworthy for 1977, when he was just a jobbing actor, although well-known from “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” and his role as a conscience-stricken slave ship captain in the TV miniseries “Roots.”

Only last month, he applauded the Olympian athlete Simone Biles for admitting to emotional vulnerabilities, and slated a UK journalist who had criticized her as a “person (I use that term lightly) that sits on his brains and criticizes people for a living.”

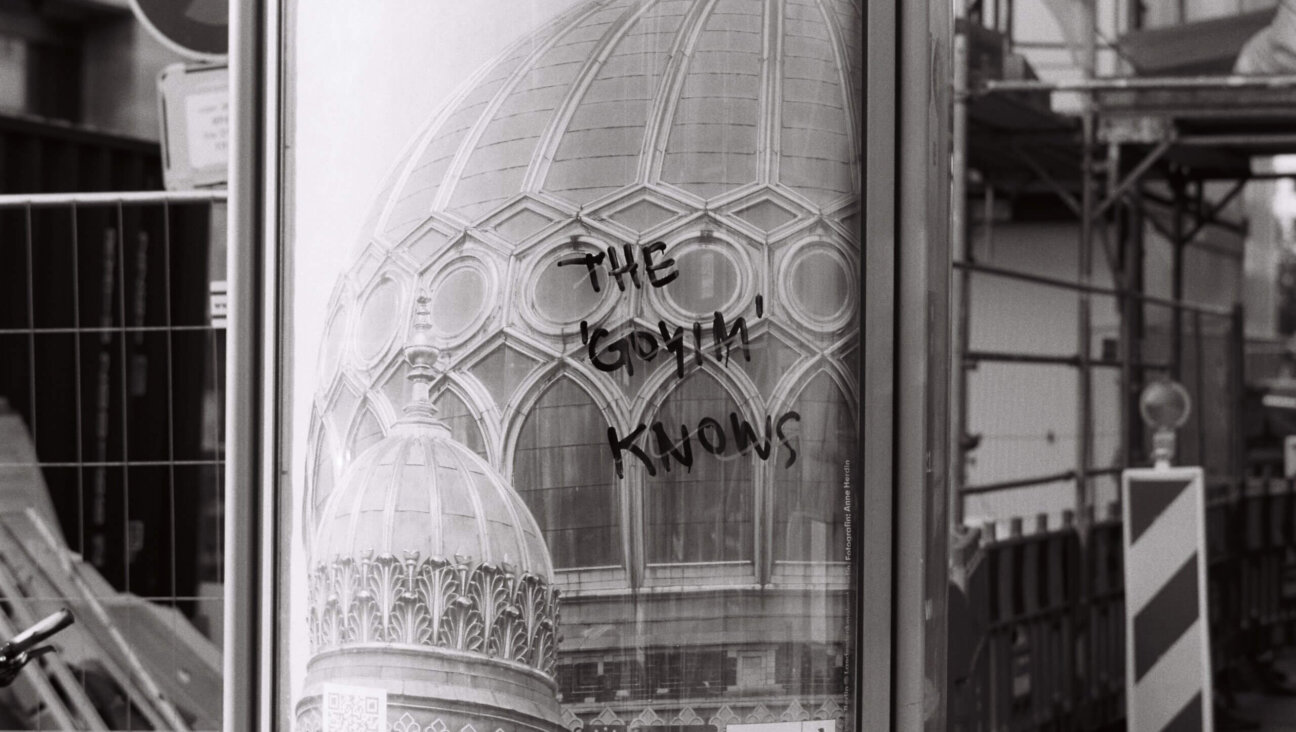

Such outspoken and sometimes defiant activism attracted brutal responses, as in 1985, when news reports noted that a Nazi swastika and the slogan “Kill Jews” had been spraypainted outside his Studio City apartment by vandals who claimed to represent the “National Socialistic Liberation Front” as an assault on “that Jewish communist pig Ed Asner.”

On this and other occasions, Asner required inner fortitude to carry on being, as he described himself to “The Jewish Advocate” in September 1997, a “Jew who goes around talking.”

Part of his strength was doubtless drawn from conveying the “grandiosity of Judaism” onstage. In 2007, he portrayed the title role of the king of the United Monarchy of Israel and Judah in the play “King David and His Concubine” at a Jewish Community Center in West Hills, California, and later was promoted to playing the Almighty himself in a political comedy, “God Help Us!” which he was still touring at the time of his death.

Other Jewish-inflected roles over the years further imbued Asner with an aura of gruff but stalwart Yiddishkeit. These included the character of the high school principal Joe Danzig in the television drama “The Bronx Zoo” and as Jacob Ascher in Sidney Lumet’s 1983 screen adaptation of E. L. Doctorow’s novel “The Book of Daniel,” inspired by the story of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

Any actor so consistently vocal would inevitably err on occasion, and Asner’s embrace of conspiracy theories involving the Sept. 11 attacks and the AIDS pandemic were an unfortunate part of his trajectory.

Unlike his personal path of confronting and understanding prejudice, spouting opinions based on inadequate understanding of structural engineering (for 9/11) and epidemiology (for AIDS) did not amount to his finest hours in public life.

At such moments, it was as if he were identifying with Milton Saltzman, a fictional character in “The Soap Myth,” another play he toured extensively in recent years on a Holocaust-related theme.

Saltzman adamantly insists that even though historical authorities such as The Yad Vashem Memorial have stated that Nazis did not produce soap from bodies of prisoners on an industrial scale, this atrocity did in fact occur.

Still in the domain of remembrance, Asner narrated “The Tattooed Torah” a short animated film adaptation of a children’s book about a child-size prayer scroll from Brno, Moravia, which was confiscated by Nazis and numbered (or “tattooed” as were concentration camp prisoners).

Into old age, Asner continued to examine his own Jewish identity with an inquisitive spirit natural in someone who underwent years of Freudian psychoanalysis, even on occasion seeking advice about his acting from his analyst. Asner admitted to the YBC that when reading newspaper wedding announcements, he still irresistibly scanned the listings to look for Jewish names: “Why am I doing that? What is this impulse, this compulsion?”

Ongoing inquisitiveness about Yiddishkeit served as the basis for Ed Asner’s lifetime of acting and humanistic activism.