The gorgeous desperation of Tony Curtis — an actor who never played it straight

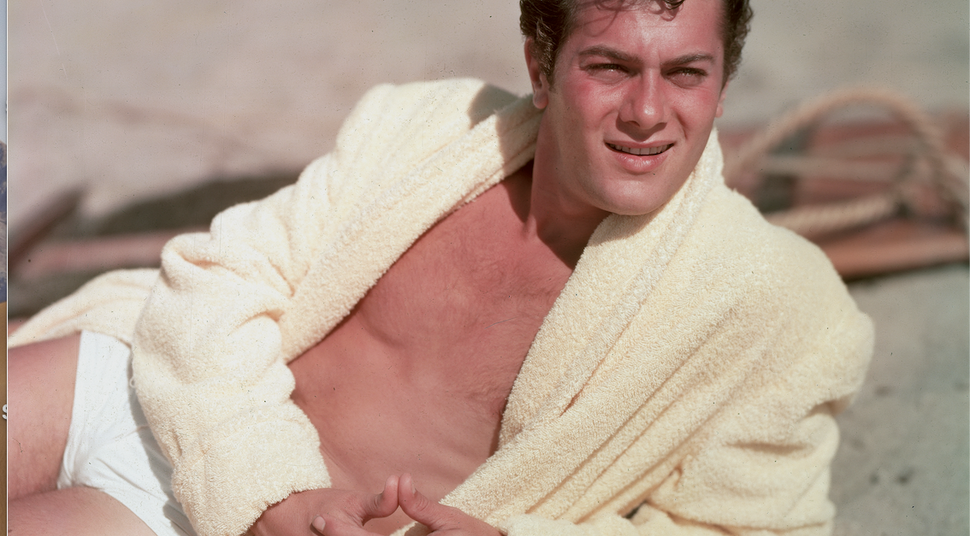

Tony Curtis By Getty Images

Long after he became rich and famous, he had a lean and hungry look. This look was his greatest gift as a performer. Few matinee idols played so many desperate men, and none was better at conveying a trembling, clenched-jaw desperation. His nastiest characters are ruthless; even the nice ones have, as the kids say, no chill. Most of them are prepared to use whatever they’ve got to get by, and because they’re played by a movie star, this usually means trading their beauty for favors.

In other words, Tony Curtis — the subject of a two-month, twelve-film retrospective at MoMA — does onscreen what all movie stars do offscreen. Stare at his face long enough and you can see Hollywood in all its glistening garbage-glory.

“Mr. Falco is a man of 40 faces, not one. None too pretty, and all deceptive.” Burt Lancaster is talking about Curtis’s character in “Sweet Smell of Success” (1957), but he may as well be talking about the man himself. In the film — maybe the greatest ever made about the stinking meat grinder otherwise known as “show business” — Curtis plays a press agent to up-and-coming actors. But in effect he’s playing an actor: his job is to be all things to all people. As shot by the great noir cinematographer James Wong Howe, his cheeks have a plastic sheen; his forehead is permanently creased with the stress of his own lies. Only the eyes seem honest, and they’re utterly cold. He is pretty, but it’s an eerie, grotesque prettiness, fit for a doll or a Venetian mask. Another character calls him “the boy with the ice cream face.”

Yacht Life: Curtis and Marilyn Monroe rehearse a scene from ‘Some Like It Hot.’ By Getty Images

If you happen to be a Hollywood leading man, you are probably beautiful, and you will probably spend much of your career in roles that make little sense when played by beautiful people. It’s a problem as old as Hollywood, and most of the time Hollywood solves it by striding right past it — hence Brad Pitt as the gorgeous stuntman in “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” Denzel Washington as the gorgeous pilot in “Flight,” Judd Nelson as the gorgeous garbage man in “The Dark Backward,” and too many other A-list absurdities to name.

Tony Curtis was as gorgeous as they come, and he made a career out of playing losers and low-lifes, none too plausibly. Yet he never seems to take his beauty for granted; he’s constantly putting it to work, wielding it like a rusty old tool.

There’s something both deeply weird and undeniably fascinating about watching him do this again and again. Female ingenues are always putting their looks to work in movies, but male ingenues, even in the post-“Magic Mike” era, rarely get to. Curtis is never a passive object of women’s attention à la Warren Beatty or Robert Redford; even when he’s lying flat, he’s the one who puts in the effort. And unlike Clark Gable or Humphrey Bogart, he makes it seem like real effort—a sheepish, teeth-gritting necessity. He never twinkles. Seduction isn’t an art in his hands, it’s a cheap trick.

Some Like It in Color: Curtis and Marilyn Monroe rehearse a scene in which he all but confesses to being gay. By Getty Images

Consider, for instance, the early scene from Billy Wilder’s “Some Like It Hot” (1959), in which Curtis sweet-talks his sort-of girlfriend Nellie into admitting she’ll be home all evening and then pounces: “Good. Then you won’t be needing your car.”

Curtis’s Bronx accent nearly wrecked his career before it had properly begun — after the release of his first big movie, the 1951 swashbuckler “The Prince Who Was a Thief,” Life mocked him for the line “Yonduh lies duh castle of duh caliph, my fadduh,” which was peculiar seeing as he never said it. But by 1959, he’d made the brisk, hard, outtuh-New-Yawk vowels a part of his persona: here, he’s so blunt about tricking Nellie into giving him what he wants that he doesn’t bother to gloat.

Later in the film, when he’s maneuvered Marilyn Monroe onto a yacht, he still can’t bear to ease up. Trying to get to third base before the owner comes back, he sprints around the hull in a jacket that looks a size too small; when Monroe kisses him, he says, “Thanks just the same” and washes out his mouth with a piece of cold pheasant. The goal, of course, is to make Monroe kiss him again, and she does, but even then Curtis doesn’t stop to wink at the audience. He’s such a diligent hustler he won’t let us catch him enjoying the fruits of his hustle.

“The Defiant Ones” (1958) is remembered as the prestige pic in which Curtis and Sidney Poitier play runaway convicts who, because they’re shackled together, must learn a Very Important Lesson about racial politics. Which it is, though its sexual politics are an order of magnitude more intriguing. Late in the film, Curtis and Poitier find their way into a lonely single mother’s house and, with her help, get the shackles off. Partly to celebrate and partly because he’s desperate for an ally, Curtis sleeps with the single mother.

The next morning, he finds Poitier and gives him a look that’s somehow sneery and apologetic at the same time. I had to do it — you understand, don’t you? the look seems to say, even as it adds, This is none of your goddamn business, anyway. By the time the credits roll, the single mother had faded away and the two prisoners are back in each other’s muscular arms. Like a number of Curtis’s most famous films, “The Defiant Ones” is a two-man love story, skimpily dressed as something else. It all but begs to be psychoanalyzed.

Joined at the Hip: Curtis co-starred with Sidney Poitier in “The Defiant Ones.” By Getty Images

So, in a different way, does Curtis. More than any star before the New Hollywood era, he wears his neuroses on his sleeve, until you’re unsure which ones are felt and which are merely affected. For much of the yacht scene in “Some Like It Hot,” he is being psychoanalyzed — “I spent six months in Vienna with Professor Freud, flat on my back,” he tells Monroe, just before lying flat on his back. “I’ve got this thing about girls. They just sort of leave me cold … Mother Nature throws someone a dirty curve, and something goes wrong inside.”

There were whispers about Curtis’s sexuality, according to the film critic David Thomson, almost from the minute he made it big. It took guts to agree to a scene in which he all but confesses to being gay, even as a way of conning Marilyn Monroe into kissing him straight again.

I’m not sure if the real Tony Curtis had an analyst, but if he did the sessions must have been something. Any aspiring actor who becomes a star has in some sense gone from rags to riches, but Curtis’s rags were ragged. Born Bernard Schwartz to Hungarian-Jewish parents, he grew up in the Bronx in the depths of the Depression. When he was eight years old, his mother was diagnosed with schizophrenia and he was sent to live in an orphanage. His younger brother later turned out to be schizophrenic, too. His older brother was killed by a car. He joined the navy while he was still a teenager, supposedly because he’d just caught the Cary Grant submarine epic “Destination Tokyo.”

After World War II, he got a job as a truck driver, and if the talent agent Joyce Selznick hadn’t spotted him at an acting workshop at the New School, he very well might have remained one for the next 40 years. Instead, he became a millionaire who got married six times, developed tastes for wine and hundred-dollar-a-gram cocaine, and partied with Sinatra (apparently, they bonded over their passion for cunnilingus).

It’s no small delight to watch the dozen films in MoMA’s Curtis program and realize that this loner, this sullen Bronx orphan who by the age of 12 had learned a few times over that he couldn’t rely on anybody, grew up to be one of the greatest screen partners Hollywood ever saw. He was never better when he had someone to share top billing with — his acting style brightened every other style it touched. At the heart of the program are four classics released between 1957 and 1960: “Sweet Smell of Success,” co-star Burt Lancaster; “The Defiant Ones,” co-star Sidney Poitier; “Some Like It Hot,” co-star Jack Lemmon; and “Spartacus,” co-star Kirk Douglas.

In all four cases, Curtis turns in performances marked by restless self-awareness; his characters are stingingly conscious of their limits and undignified in their refusal to accept them, none more than the ice cream-faced Mr. Falco. Many of the great noirs end with the leading man stoically accepting his fate, but as “Sweet Smell of Success” comes to its close, Curtis radiates pure animal panic.

By themselves (and without the benefit of the naturalistic Method acting that emerged in the 50s and eventually spawned a whole army of alluring antiheroes), none of Curtis’s four performances would be sturdy enough to support a whole film. But because they’re paired with a second leading role of cooler confidence — Lancaster’s stately wickedness, Poitier’s dignified smolder, Lemmon’s sunniness, even Douglas’s impassioned rabble-rousing — they work like a dream. Onscreen, Curtis makes love for the opposite sex seem like an unscratchable itch, but there’s nothing anxious about his characters’ love for the same sex: they bond with other men instinctively and uncontrollably. Even in “Sweet Smell of Success” and “The Defiant Ones,” when Curtis is playing a man who hates another man, you sense the longing silently nourishing the hatred.

It’s not hard to see why Curtis had a reputation for being gay or bisexual. For what it’s worth, there’s no evidence to support the rumors that he was, which would put him in the minority as far as 50s male sex symbols are concerned (Lancaster, Grant, Marlon Brando, James Dean, Montgomery Clift, Rock Hudson — was anybody fully straight back then?). We can never know for sure, but I daresay Curtis’s performances are more intriguing if you accept that he was straight (just as Hudson’s get more intriguing once you find out he was gay). He shows what hard work heterosexuality is, even if you happen to be heterosexual, and how you needn’t be homosexual to favor the comparative ease and warmth of the same-sex bond. Perhaps this point is always hidden somewhere in Hollywood romance; what’s remarkable about Curtis is how little effort he makes to hide it. In an era when male stars were extravagantly paid to lie to the camera about sex and sexuality, his face always told the truth.

At Home With His Art: Few major Golden Age stars who lived to be old had such brief heydays — Curtis was already in decline in the mid-60s. By Getty Images

That era was nearly over by the time he got famous. Few major Golden Age stars who lived to be old had such brief heydays — he was already in decline in the mid-60s. In the narrowest sense, Curtis’s career waned because his beauty waned, which isn’t to say that all sex symbols are through as soon as they lose their sexiness. As early as 1963, Burt Lancaster had pivoted to autumnal, self-abasing performances; it’s bizarre, considering how self-abasing Curtis could be at the height of his popularity, that in his doughier years he never attempted anything like “The Leopard” (1963) or “The Swimmer” (1968) or “Atlantic City” (1980). He probably could have if he’d really wanted to. But there were wives and affairs and Rat Pack parties, and maybe we shouldn’t blame him for losing some of his drive. He’d already crammed a whole, majestic career into half a decade.

The closest he came to a Lancaster-esque pivot was “The Boston Strangler” (1968), one of the great forgotten films of the late 60s. To play the real-life serial killer Albert DeSalvo, Curtis developed a halting, gaping manner of speech and a glassy-eyed thousand-yard stare, tranquil in its destructiveness. Where most serial killer movies relish the thrill of the hunt, “The Boston Strangler” instead emphasizes moral drama — DeSalvo gets nabbed with a half-hour to go and spends the rest of the film staggering toward a confession. Of all the killers in all the films in all the world, Curtiss’s is among the most sympathetic and frightening — frightening because Curtis makes him so sympathetic. Even when he’s trapped in a padded cell, gazing at nothing, he makes us feel the sickness gnawing away at his mind.

Curtis got a Golden Globe nomination for his trouble, but critics kept cool and audiences weren’t much kinder — a tad surprisingly, considering how many creepy-queasy megahits there were in 1968. Perhaps there’s some alternate universe in which “The Boston Strangler” is iconic and “Rosemary’s Baby” is the underrated gem (you can hear Curtis’s voice in the latter, by the way — he’s the poor wretch who Satan blinds so that John Cassavetes’s struggling actor can become a star!).

In our universe, Tony Curtis is remembered as a creature of the 50s who burned out soon after. The official MoMA description of this series suggests that he was “one of the first casualties of the New Hollywood’s shift to naturalism,” uncomfortably wedged between cinema’s Golden and Silver Ages. This is right but also wrong, for discomfort was always well within Curtis’s comfort zone. May these 12 films be a monument to a one-of-a-kind performer: a street kid disguised as a pretty-boy, a supporting actor trapped in a star’s body, a handsome mutant who’s stood the test of time because he never really fit in.

Beginning on September 29 with ‘Flesh and Fury,’ MoMA is hosting a retrospective of Tony Curtis films as part of its ‘Modern Matinees’ series.

Jackson Arn is the Forward’s contributing art critic.