The AIDS crisis strained his relationship with Judaism. Now, it’s integral to his art — and activism.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

In 1993, artist and activist Gregg Bordowitz premiered his film “Fast Trip, Long Drop,” a not-quite documentary that made for a biting critique of media coverage of the AIDS crisis.

The film, in which Bordowitz plays a defiant talk show guest named Alter Allesman — Yiddish for “old everyman” — was shown widely at LGBTQ and Jewish film festivals. After one showing at KlezCamp, a now-defunct Klezmer music and Yiddish festival, an attendee stood and asked Bordowiz a question.

“Why did you bring this here?” he asked. “Is this a good thing for the Jews?”

Bordowitz, now 57, says audience members continue to ask that question about the film — still his most famous work — at nearly every Jewish festival screening.

Bordowitz’s Jewish upbringing had long been an inspiration for his art. But when he was diagnosed with HIV in 1988, he, like other queer Jews, found himself on the fringe of Jewish society and largely abandoned by traditional institutions.

In response, he said, he and his peers created their own traditions and commentaries. His sense of shifting identities became, alongside the resistance and radicalization sparked by the AIDS crisis and other public health failures, a defining theme of his work — one amply apparent in “I Wanna Be Well,” a retrospective of his work currently on display at MoMA PS1.

Installation view of Gregg Bordowitz’s “Fast Trip, Long Drop” (1993) in the exhibition “Gregg Bordowitz: I Wanna Be Well.” Photo by Kyle Knodell

That exhibit, which includes film, performance art, drawings and poems, debuted at Reed College’s Cooley Art Gallery, and was then featured at the Art Institute of Chicago before moving to MoMA PS1, where it will be on exhibit until October 11. Bordowitz takes particular pride from the fact that MoMA PS1 is located in Queens — the borough where he first learned to paint.

He grew up in the neighborhood of Glen Oaks, raised largely by his mother and grandparents, who switched to speaking in Yiddish whenever he walked into the room. He quickly learned to understand the language, and to tone down his “Yinglish” in non-Jewish friends’ homes. “It was my first awareness of difference,” he said. Code-switching, or adapting language and presentation to different cultural contexts, would later become a major theme in Bordowitz’s work.

At his grandfather’s insistence, he attended an Orthodox Hebrew school, and soon fell in love with both religion and art. As a child, his mother sent him to a neighbor’s house for amateur painting classes, where he worked alongside adults, often crafting Jewish-themed paintings. Shortly after his Bar Mitzvah, his mother and step-father moved the family to Long Island, where he found a refuge for his burgeoning queer identity in his school’s art room.

“My family wanted me to be a doctor or a lawyer or a rabbi, in that order,” he said. “I knew that I would go to school for visual arts.”

In 1982, at 18, Bordowitz moved to Manhattan to attend the School of Visual Arts. He soon gravitated to the Lower East Side, where he relished the neighborhood’s enduring Jewish character, delis and Judaica stores.

“Part of being a downtown artist was that a lot of the people I knew were Jewish,” he said. “We were really into being in the neighborhood where our grandparents landed.” He joined a flourishing queer Yiddishkeit scene, defined by a renewed, counter-cultural interest in Ashkenazi American cultural touchstones.

“Klezmer bands were forming like punk rock groups all over the place,” he said. “I was looking for an anti-Zionist American Jewish way of being, and I found it there.”

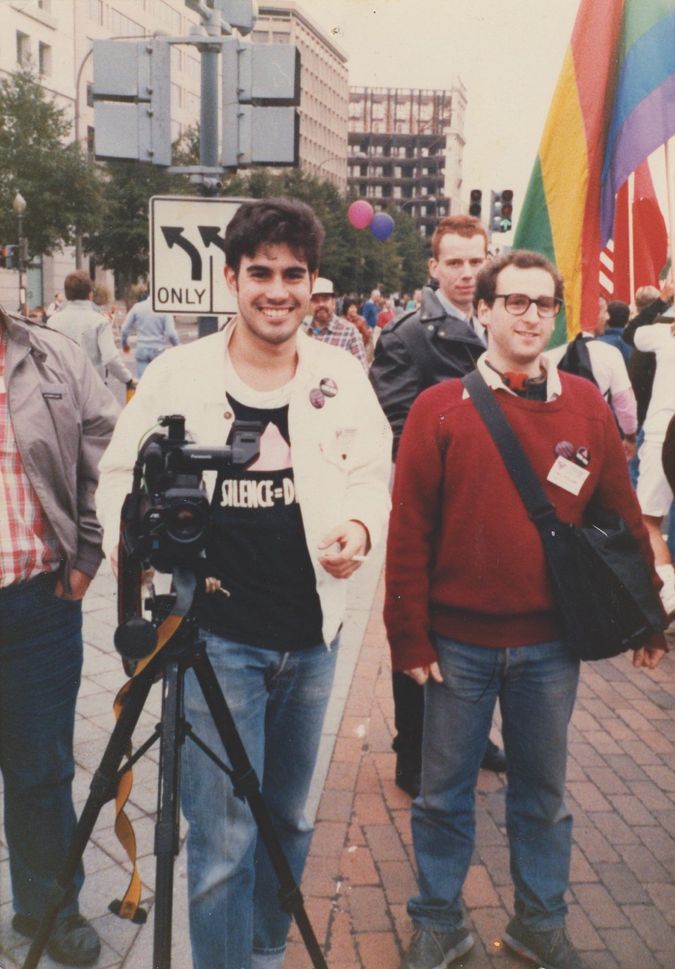

Gregg Bordowitz with David Meieran filming for Testing the Limits Video Collective, founded to document AIDS activism, in Washington, DC. 1987. Courtesy of Gregg Bordowitz

Then came the AIDS epidemic, which struck Bordowitz’s Lower East Side queer community extremely hard. Bordowitz became heavily involved in HIV/AIDS activism, including as a very early member of the grassroots political group ACT UP. His activism brought him to work in partnership with religious institutions, including Black churches and Quaker congregations.

But, Bordowitz said, “When it came to talking to Jewish organizations, it was not welcome,” he said. “I was very angry at organized Judaism during the AIDS crisis.”

Yet while Jewish organizations, he said, weren’t receptive to his advocacy, queer Jews were heavily involved in HIV/AIDS activism. In its early days, some media organizations mistook ACT UP for a Jewish organization, in part because its first flyer featured a Jewish star and the poem “First They Came” by Martin Niemöller. And in 1989, Bordowitz and other queer Jews in the movement held the first ACT UP seder. That first year, the seder attracted 30 attendees, before doubling to 60 people in its second year, and 90 people in its third.

“We attached the seder to our struggle,” Bordowitz said.

Bordowitz’s creative work also began to expand and change during the early AIDS health crisis. He started using filmmaking as a tool for documenting ACT UP protests, and co-founded a media collective dedicated to the group. He also began producing improvised video diaries and films about himself and his friends, which were intended to counter mainstream narratives about the AIDS crisis and create complex testimony about the human toll of the epidemic.

In 1988, Bordowitz was diagnosed with HIV. By 1993, in the same period that he was working on “Fast Trip, Long Drop,” he had become extremely ill. Unlike many of his friends, Bordowitz survived, and his close contact with death became a major theme in his artwork from the time period. In 1996, when a breakthrough was made in the understanding of drug therapies for managing HIV, greatly improving available treatment, Bordowitz used charcoal to draw a series of six self-portraits examining the effects of the early treatments on his body.

Installation view of Gregg Bordowitz’s “self-portraits in mirror” (1996) in exhibition “Gregg Bordowitz: I Wanna Be Well.” Photo by Kyle Knodell

Bordowitz’s health improved, and in 1997, he found a way to return to a form of institutional Judaism when six of his friends from ACT UP decided that they wanted to have adult B’nai Mitzvah ceremonies. They chose to conduct those ceremonies through the progressive Jewish congregation Kolot Chayeinu in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and Bordowitz has been a member ever since.

“I found a spiritual home,” he said of the temple. Even after he began to teach film at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1998, he continued to visit New York City every month and remained committed to the congregation. These days, his religious practice includes wearing a yarmulke and observing Shabbat.

And Judaism continues to affect and inspire his work, which today often meditates on his identity as a queer Jewish man living with HIV. While his art has continued to evolve, he said, the reasons he continues to weave together shifting and intersecting parts of his identity have changed little from when he was a young man showing “Fast Trip, Long Drop ” at KlezCamp.

When that long ago audience member asked his question — implying, Bordowitz understood, a question about why he would insist on bringing together his identities as an observant Jewish man and a queer person living with HIV — Bordowitz had a ready answer.

“Which part of me do you want to leave the room?” he said. “Which part of me do you want to stay?”