The Anne Frank play that was too dark, honest and Jewish for Broadway

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

In 1955, a decade after Anne Frank perished at Bergen-Belsen, “The Diary of Anne Frank” opened on Broadway.

It won the Pulitzer Prize, a Tony Award and the New York Drama Critics Circle award for best play. It would be produced all over the world, and adapted into a movie that was nominated for eight Oscars and won three, helping to make the Jewish teenager the Holocaust’s most well-known victim.

Anne Frank in 1942

Perhaps more than the diary itself, published three years earlier, the theatrical version of “The Diary of Anne Frank” gently introduced a subject many preferred to avoid. The play’s most quoted line, uttered by Anne, is shockingly hopeful: “In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart.”

But there was another play, a darker and more Jewish adaptation of her diary, one truer to Anne’s words. Few have seen it.

Written by Meyer Levin, a Jewish journalist and author who spent the post war years in Europe and had won the trust of Otto Frank — Anne’s father and the only member of her immediate family to survive — the play was performed in Israel in 1966 by The Soldiers Theater, part of the Israeli Defense Forces, and a few other times for mostly small audiences.

Those enlisted to bring Anne Frank to Broadway had read Levin’s play. Cheryl Crawford, the first producer attached to the project, considered it “too faithful” to the diary.

The story of Levin’s script, and its rejection by the New York theater and publishing worlds and Otto Frank himself, is the subject of another piece of theater, Rinne Groff’s “Compulsion or The House Behind.” This semi-fictional play about the Levin play debuted off-Broadway more than 10 years ago at The Public Theater starring Mandy Patinkin. It’s currently in the middle of a run at Washington’s Theater J.

Groff named the play “Compulsion” to refer to themes it shares with Levin’s bestselling 1956 novel of the same name, about the Leopold and Loeb murders. She gave it a second title, “The House Behind,” to refer to the Frank’s hiding place, distinguish the play from Levin’s book, and highlight its concern with the story behind the story. “This is just a backstage drama,” she said.

Paul Morella as Sid Silver in Rinne Groff’s “Compulsion or The House Behind” at Theater J. Photo by Stan Barouh

That drama — divided into two acts, the first mostly set in New York, the second in Israel — probes the psyche of an author desperate to see his most beloved work performed on stage. Levin had chronicled the lives of Holocaust survivors in Europe, and as they made their way to Palestine. He believed that only a victim could capture the Holocaust’s epic horror. After reading her diary in 1950, he decided that this victim was Anne. “Here was the voice I had been waiting for,” he wrote in “In Search,” his 1950 autobiography, “The voice from the mass grave.”

Get the Forward delivered to your inbox. Sign up here to receive our essential morning briefing of American Jewish news and conversation, the afternoon’s top headlines and best reads, and a weekly letter from our editor-in-chief.

Levin’s play included several passages from the diary in which Anne contemplates antisemitism, and the plight of the Jews. Their absence from the Broadway hit, written by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, incensed him. In “Compulsion,” Groff renames Levin “Sid Silver,” and builds a character consumed by rage. Everyone involved in the Broadway production is an antisemite to him, even Otto Frank, whom Levin actually sued, alleging plagiarism.

Voice from the grave

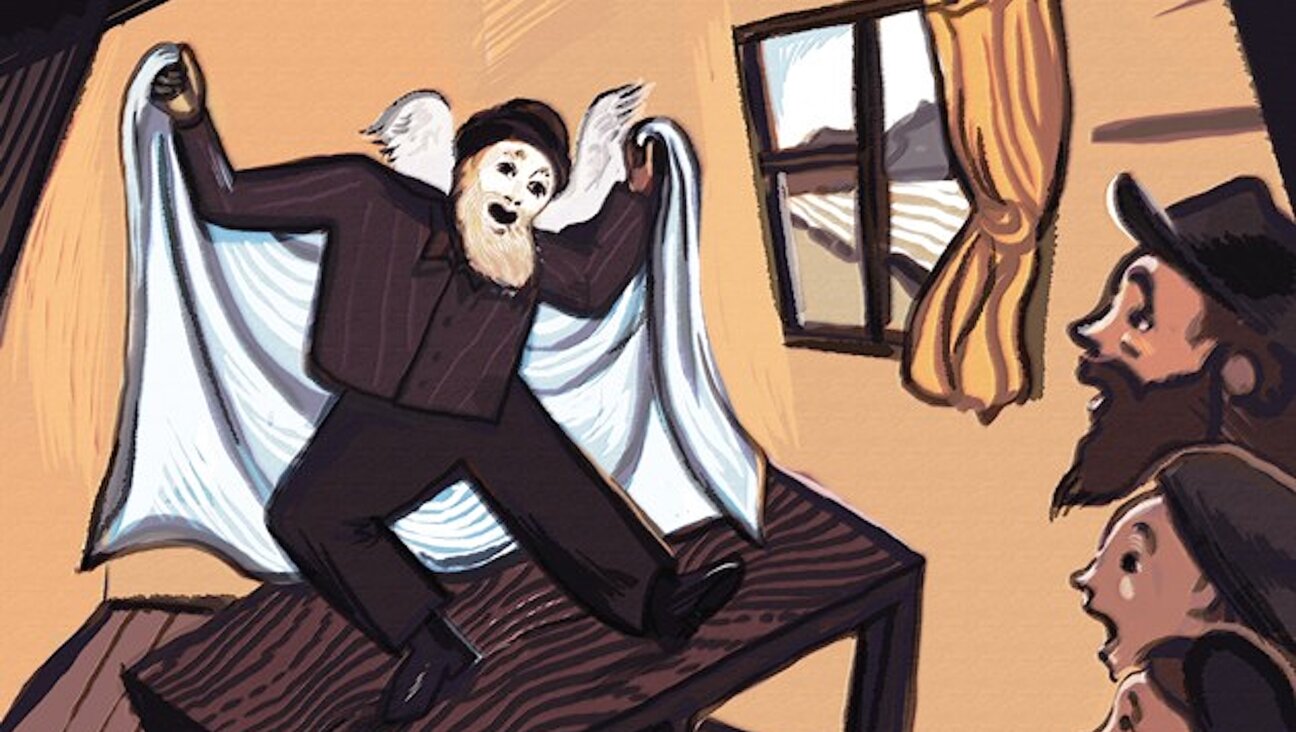

Literally hanging over the struggle in “Compulsion” over who gets to tell her story is Anne herself, who appears in the play as a marionette, visiting from the dead. Those skeptical of the idea of puppets in theater for adults may well feel differently after watching how Anne, pulled by strings, becomes an apt metaphor in a play about people fighting to control her legacy.

Puppet Anne Frank moves fluidly and hauntedly, wrapping her arms around human actors and cuddling up to them in bed. She is melancholy, provocative and, unlike Anne the diarist, fully aware that she lived her last months in Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen. Voiced offstage, she declares: “Everyone likes me better dead.”

Paul Morella as Sid Silver with puppet of” Anne Frank and Matt Acheson, puppeteer, in “Compulsion or the House Behind,” at Theater J in Washington, D.C., from Jan, 26 to Feb. 20, 2022. Photo by Stan Barouh

But Anne won’t weigh in on the central question of “Compulsion.” As she declares at the beginning of Act 1: “I don’t own the copyright.”

Silver, to his torment, doesn’t own it either. “Compulsion” pits him against two publishing executives — one of them Jewish — who shepherd the first English edition of Anne’s work, “The Diary of a Young Girl” into print. They eventually dismiss Silver as a narcissistic crackpot, but not before reminding him that, though an accomplished writer, he has no bona fides as a playwright or legal right to Anne’s words.

Miss Mermin, the Jewish editor, who is Anne’s exact age but grew up safe from the Nazis, prides herself on introducing the world to Anne’s diary, the work that has also made her career. She’s played by an actress who also plays Silver’s wife, a writer in her own right who loves her husband deeply, but sees how his compulsion threatens their marriage, family and his career. Anne is your “mistress,” Mrs. Silver tells her husband.

Current events

The second act of “Compulsion” moves the drama to the one place that Silver decides he can take control of his life and Jews can take control of their history: Israel. In Tel Aviv — as Levin did in 1966, before Otto Frank shut it down — Silver stages his version of the play, copyright be damned.

“Why is it irrational to believe that here in Israel, I can control my own fate?” he asks. After the Holocaust, he suggests, Jews have earned the right not to follow rules that have so often persecuted them.

Miss Mermin is not so sure. As she defends her efforts to popularize the diary, she also questions Israel, remarking that the new Jewish state has not signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

The question of who controls Anne’s story in “Compulsion” raises larger ones — who gets to frame the history and meaning of the Holocaust? Who gets to judge the Jewish state?

The questions persist.

Less than a week into the run of “Compulsion” at Theater J, Whoopi Goldberg on the national television show she co-hosts declared that the Holocaust “was not about race” but rather “man’s inhumanity to man,” and later described it as white people hurting white people. She then apologized. ABC News suspended her for two weeks.

Levin surely would have seized upon Goldberg’s remarks as yet more evidence that non-Jews are too ready to define the Holocaust and efface the Jewishness of its victims.

Playwright Rinne Groff Courtesy of New York University

When I spoke to Groff, the playwright of “Compulsion,” she said the controversy reminded her of Silver’s rant in the play against a phrase delivered by Anne in the Broadway version, a phrase that does not appear in her diary. “We’re not the only people that’ve had to suffer,” Broadway Anne says. “There are always people that’ve had to … sometimes one race … sometimes another.”

That’s exactly what the Goldberg controversy was about, Groff said. “Do we look at this event on something on the continuum of human atrocity? Or do we look at it as something unique, that can only be discussed in terms of anti-Jewish feelings.”

“That question,” she said, “will always be with us.”

“Compulsion or the House Behind” is at Theater J at the Edlavitch DC Jewish Community Center through Feb. 20. It can be seen in person or streamed. Tickets are available at the Theater J website.