Remembering the only Jew on the first Freedom Ride – 75 years ago

Igal Roodenko, who received a 22-day prison term for his action, was the only Jewish participant on the trip, which led to the better known Freedom Rides of 1961.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

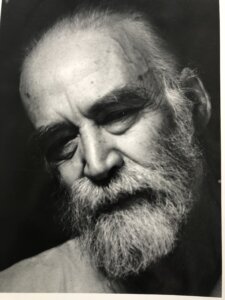

In a lifetime of activism and countless speeches to groups large and small, Igal Roodenko left behind a healthy number of photos of himself upon his death in 1991. Most show his shaggy hair and beard and casual, if not worn, attire. For decades, the world was only aware of one where he was wearing a suit. On Saturday, a newly discovered image will make it two – though it’s the same suit in both.

The occasion was the first Freedom Ride, of whites and Blacks challenging segregation on Southern buses and trains. The two-week trip, dubbed the Journey of Reconciliation, concluded exactly 75 years ago.

If that math sounds off, it’s because that first ride wasn’t in the 1960s, as much of the public believes, but 1947, long before the Civil Rights Movement had taken hold. Likewise, the Jewish participation on it was not the same as it would be once the movement was in full force. On the 1947 ride, Roodenko was the only Jew.

Born in 1917 and raised on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Roodenko was the child of immigrants from Ukraine. His father, an ardent Zionist, first immigrated to Palestine before leaving again for the United States.

Roodenko followed his father’s politics and beliefs in a home steeped in Zionism and socialism (one has to assume the Forward was a staple in the household) as well as atheism. Intending on a career helping to make things grow in the desert of an Israel still yet imagined, he entered Cornell University in 1934 to study botany — and quickly found it bored him. He stuck it out, however, and met other radical students who nurtured his growing pacifism.

He gave botany a shot with the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Georgia before turning to social action for good, first for the American Emergency Committee for Zionist Affairs in New York City, and then the AFL- CIO when World War II came along with a draft notice. Well-aware of Hitler and Nazism, he faced his ultimate test as a Jew.

“The World War II experience for a lot of pacifists was a very difficult one, first because the war against Hitler was probably as justified a war as anyone can probably deal with,” he said in a 1974 oral history.

“So those of us who were pacifists in spite of all the good reasons for not being pacifists had to do an enormous amount of soul-searching and re-thinking of how do we justify non-participation in a crusade against such a manifest evil in the world?”

Ultimately, Roodenko decided that no matter the cause, he could not take a human life, and sought conscientious-objector status. As an atheist Jew, making the case that his pacifism was based on faith was a tough sell to the draft board; the designation at that time was largely reserved for members of the Christian peace churches, such as the Quakers and Mennonites..

He succeeded, however, and was granted a spot at a civilian work camp – only to walk away from it, deeming the work both meaningless and still part of the war effort. That meant federal prison, and he reported for a three-year sentence in Minnesota as the war drew to a close. He joined a hunger strike with other activist prisoners, and was paroled in December 1946.

It was just in time to make history. Earlier that year, the Supreme Court had outlawed segregation in interstate (but not intrastate) transportation. It ruled in favor of Irene Morgan, a Black woman who, already sitting in the back of a bus traveling between Virginia and Maryland, refused to give up her seat to white passengers. Representing her was then-NAACP lawyer Thurgood Marshall, who argued that Morgan’s arrest was a violation of the Interstate Commerce Clause as “an undue burden on commerce” that would force passengers to move from seat to seat as the bus traveled through segregated and non-segregated states.

The high court agreed. But the Southern states refused to enforce the ruling. An interracial group of activists from the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation and the fledgling Congress of Racial Equality seized on the idea of a ride through the South, in which Black and white travelers holding interstate tickets would violate the now-superceded state segregation laws. Roodenko unhesitatingly joined the group for the April 1947 trip through the Upper South.

That’s where the suit and tie come in. Knowing they were upsetting the norms of the South, the riders committed themselves to remaining nonviolent and comporting themselves like gentlemen. That respectability was captured in a photo of nine of the 16 riders in front of the Richmond, Virginia, offices of an NAACP lawyer, Spottswood Robinson. Until recently, it was thought to be the only image of the riders on the trip.

On the buses, they did not travel as one obvious group. A Black and white pair would sit up front, directly behind the driver. Another pair would sit in back, in the Black section. Another rider would sit by himself, among his racial group, ready to sway public opinion if needed. He would also carry the bail money.

The riders had already endured several arrests by the time they planned to leave Chapel Hill, N.C., on April 14. A Black and white pair sitting up front, Andrew Johnson and Joe Felmet, were arrested. Their vacated seats were taken by Roodenko and Bayard Rustin, who later would become a pivotal figure in the Civil Rights Movement. They, too, were arrested – and the activity caught the attention of a group of white cab drivers who were incensed by their integrationist actions and punched one of the riders.

The riders were saved by a supportive white minister, who drove them to his home with the cab drivers in chase, one cab ending up on the minister’s lawn. With threats persisting, including an anonymous call to “Get those damn n—s out of town,” they left that night with a police escort to the next town.

Over the trip’s remaining days, the riders amassed more arrests but faced no further violence. When it concluded on April 23, they deemed it a success and looked to the NAACP to make good on a loose promise to represent them in court. They even wrote a song about it:

“You don’t have to ride Jim Crow!

You don’t have to ride Jim Crow!

Go quiet-like if you face arrest

NAACP will make the test.

You don’t have to ride Jim Crow!”

Yet the NAACP ultimately did not take their case, and the Chapel Hill convictions stood. Johnson paid the fine and Roodenko, Rustin and Felmet reported to prison.

As a Jew, Roodenko was singled out for special treatment, with Rustin recalling the judge lecturing him:

“‘Now Mr. Rodenky’ — purposely mispronouncing his name, ‘I presume you’re Jewish,’ and Igal says, ‘Yes, I’m Jewish.’ He says, ‘Well, it’s about time you white Jews from New York learned that you can’t come down here bringing your nigras with you to upset the customs of the South. Now, just to teach you a lesson, I have your Black boy 30 days on the chain gang, now I give you 90.’”

Felmet, to whom the judge attempted to give an even longer sentence of six months for being a white Southerner “who should have known better,” recalled their lawyer telling the judge that the maximum sentence was 30 days. With North Carolina prisons segregated, Rustin reported to the Black facility and Felmet and Roodenko to one for whites, all three sentenced to hard labor on a chain gang. Their food was mostly beans cooked in pork grease.

“That created a problem for Igal because he was an ethical vegetarian,” Felmet recalled.

It would hardly be the only adversity he’d faced. By then, Roodenko was already a leader of the pacifist War Resisters League, serving on its executive committee from 1947 to 1977 and as its chair from 1968 to 1972. He later became active in the interracial gay group, Men of All Colors Together.

Having abandoned botany, Roodenko made his living as a printer, once attracting Jackie Kennedy as a customer for a volume of her husband’s writings. He fulfilled the order but, true to his uncompromising animal rights ethics, refused her request to bind it in leather.

His activism never ceased, and in 1991, the day before planning a pacifist mission to Greece and Turkey, he died after a heart attack. His yahrzeit is April 28.

And that second photo? It was discovered earlier this year in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection by Louis Battalen, a researcher working on a book about Roodenko’s fellow pacifist and friend, Juantia Nelson. It will be unveiled Saturday at an online forum sponsored by the Freedom Rides Museum in Montgomery, Alabama, and the Fellowship of Reconciliation.

Without giving anything away, the photo is one more opportunity to see a lifelong activist and advocate for human, and animal, rights in a suit – apparel that may disguise, but in no way diminishes, his radical struggles for justice.

Robin Washington is the Forward’s editor-at-large and producer of the public television documentary about the 1947 Freedom Ride, “You Don’t Have to Ride Jim Crow!” He will be part of an online forum co-sponsored by the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the Freedom Rides Museum at 3 p.m. CT on Saturday, April 23 that may be viewed at https://bit.ly/1947freedomride

Pre-registration is not required.