How Adam Yauch graduated from bratty Beastie Boy to a man of wisdom and peace

Ten years ago, MCA died, leaving behind an estimable if complicated legacy

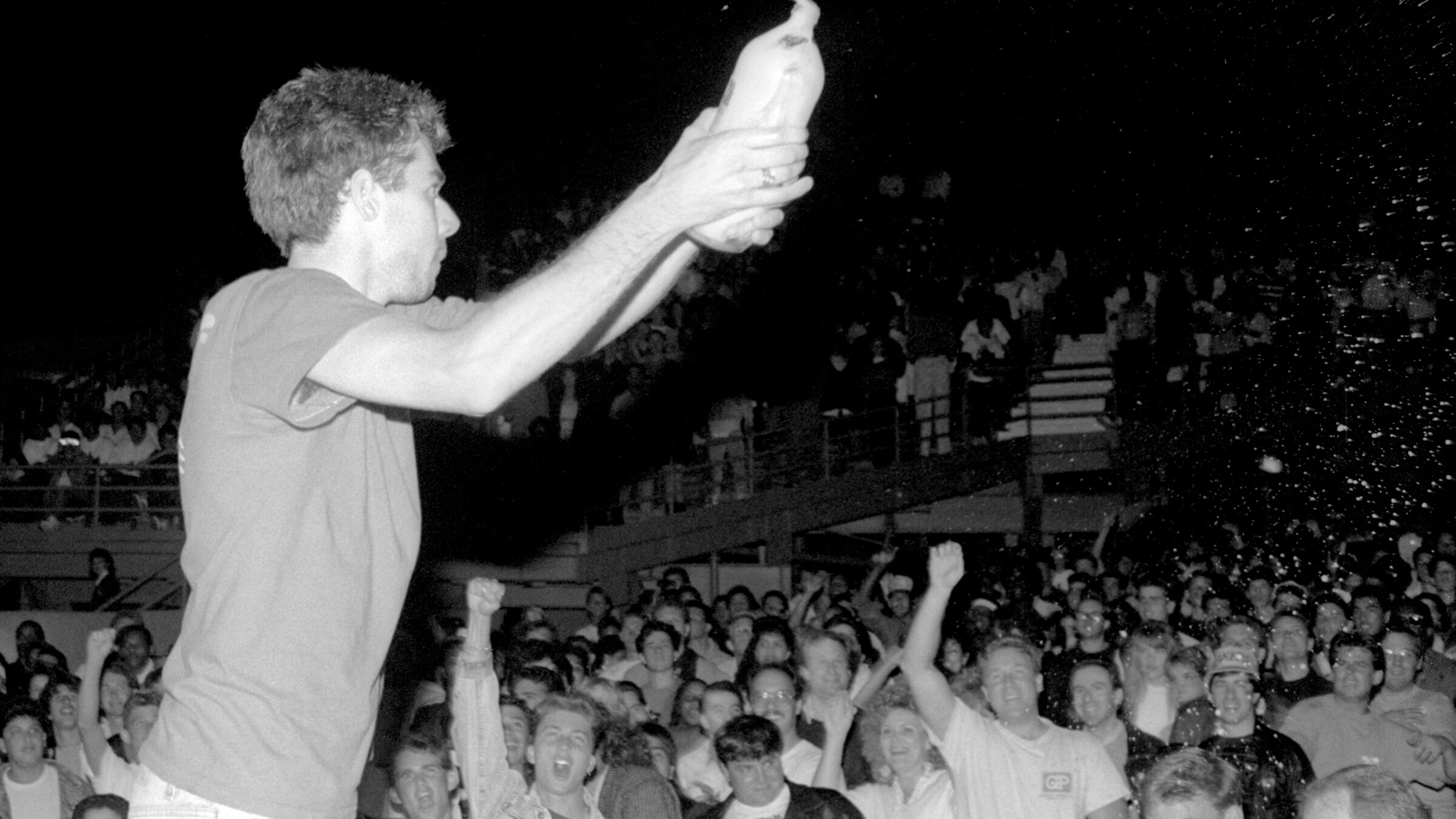

LOS ANGELES, CA – JUNE, 1987: American rapper, bass player and filmmaker Adam Yauch, aka MCA, (1964-2012) of the American hip hop group The Beastie Boys, throws beer on the crowd during a concert circa June, 1987 at the Greek Theatre in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Lester Cohen/Getty Images) Photo by Getty Images

It was the autumn of 1989 and people were starting to take the Beastie Boys seriously, or at least thinking the bratty band had been hit by a tiny lightning bolt of maturity.

The Beastie Boys — Adam Yauch (MCA), Mike Diamond (Mike D) and Adam Horovitz (King Ad-Rock) — weren’t sure if they wanted to have any truck with that kind of revisionism.

“I wanna know,” Diamond asked rhetorically, as I sat with the three Beasties at the Four Seasons Hotel Boston, “what physically, actually happened where people will say, ‘I used to think the Beastie Boys were jerks, but now I think they’re all right?’”

“Are people saying that?” responded Yauch.

“Somehow, people do say that,” said Diamond.

Yauch immediately shot his middle finger in the air at those imaginary people and hurled an undersized Sharper Image basketball he’d been clutching against the wall. The rebound bounced off Horovitz’s head.

“I think that pretty much sets the record straight,” said Diamond. “Sometimes, they say, actions speak louder than words.”

Ten years ago, on May 4, Yauch lost a three-year fight with a rare salivary cancer.

Both the actions and words of Yauch, who died at 47, really did shift over time, from his wiseacre youth toward what some people might now call a more “woke” middle age. (I doubt he’d like the term; I don’t. But it’s out there to suggest some sort of turning point of enlightenment.)

A few days after his death, Diamond posted this on social media:

https://m.facebook.com/beastieboys/photos/a.139327313944/10150889667668945/?type=

Horovitz offered this: “As you can imagine, s— is just fkd up right now. but I wanna say thank you to all our friends and family (which are kinda one in the same) for all the love and support. I’m glad to know that all the love that Yauch has put out into the world is coming right back at him.”

At first, the Beastie Boys were a joke. Whether it was a good one or a bad one, that was up to the listener. In 1981, they were three teenage Jewish kids from New York playing fast and nasty punk rock. No anomaly there: Jews were a dominant force during the early punk years.

Then they became a rap act. How bizarre, how comical. These white boys doing what was then almost exclusively a Black form of music, all three swapping lines and boasts, topping the beats with their own particular hedonistic, adenoidal, rapid-fire, caustic-funny worldview.

Madonna loved them. Well before their first album came out, she had the Beastie Boys open her 1985 U.S. arena tour. There, they were routinely ignored, hooted or booed. They hooted right back, sometimes seeming to like the confrontation more than applause.

Then, in late 1986 and 1987, the dam broke open. The Beasties blasted to the top of the charts with their debut album, “Licensed to Ill,” propelled by the ubiquitous anthem, the snotty, frat-boy hit single “(You’ve Got to) Fight for Your Right (to Party).”

The rappers were all in their early 20s when I spent a couple of days with them in Cleveland for The Boston Globe just as the album hit No. 1 and they were on a headlining tour.

At the sold-out Public Auditorium concert, the Beasties bounded across the stage as their DJ, Hurricane, spun discs. They showered the crowd with barbs and insults, and mostly ignored a scantily clad woman they had dancing in a cage. Yauch spotted a sign on the balcony that read “I want to rape MCA” (that’d be him). He climbed a speaker column to get closer, but ultimately returned to the stage.

The floor was slick, soaked by the endless series of Budweiser cans the Beasties opened, guzzled, hurled, spat and sprayed across the stage and into the crowd. It was a punk rock club mentality brought to the arena stage.

They mixed declamatory rap and heavy metal styles, cutting each song with scathing wit and punky aggression. Sample lyric from “The New Style”: “Some voices are treble/Some voices are bass/We got the kind of voices that are in your face.”

And there was “Rhymin’ and Stealin’”: “Skirt chasin’/Free basin’/Killin’ every village/We drink and rob and rhyme and pillage.”

The 10,000 fans in attendance lapped it up. The Beastie Boys stood up — proudly, defiantly, aggressively — for sex, drugs, drink, junk food, cartoon violence and general mayhem. Say this, though: Even if they were rude, they were more clever than crude.

If you took their songs literally, you had a litany of thievery, thuggery, drug taking and sexual hijinks; if you took them figuratively, you had a lurid, underground comic book set in a rap/rock framework. Anger and humor joining hands and going for a joyride.

Offstage — back in their hotel rooms — the Beastie Boys continued to let it fly, joking about rumors as to which one had overdosed and died, dissing the topless women they’d taken photos of in their tour scrapbook, insulting one another with the the term “homo.”

As it happened, Yauch was having girl trouble. A young woman — she said she’d been a Playboy model — had hooked up with him and was following the band from city to city. Though pretty, Yauch thought her crazy and instructed one of the band’s attendants to tell the road manager to make sure she was gone after this show: “If nothing else happens in the world, if the gig falls through, make sure this girl ends up on the bus going away from us. Tonight.”

The Beastie Boys were dealing with the oddest of exigencies, a seemingly meteoric rise to fame after a few years of kicking around the lower level of grungy punk clubs, where a nasty attitude was part and parcel of the game.

“Licensed to Ill” was the first rap album to hit No. 1 on Billboard’s charts, certified platinum three months after its late-1986 release. Now, they were these improbable rock stars.

“The rock star thing is very strange,” Yauch told me, over dinner with the other Beasties, the day after the Cleveland concert. “We don’t come from that kind of background. We’ve never been obsessed with any big groups. We just come from the club scene. Now, all of a sudden, we’re big stars and it’s really weird that all these people that aren’t the kind of people we ever hung out with suddenly like us.

“Most of the people who are stupid enough to come up to you are really annoying people. Anyone you might actually want to hang out with — chances are they aren’t demented enough to walk up to you.”

Mike D chipped in, “I think if I wasn’t in the Beastie Boys, I’d definitely hate some of this.”

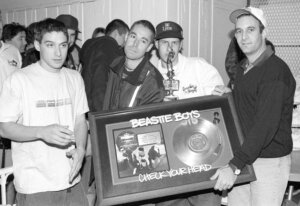

- LOS ANGELES, CA – JANUARY, 1993: American rapper, guitarist and actor Adam “Ad-Rock” Horovitz, American rapper, bass player Adam “MCA” Yauch (1964-2012) and American rapper Michael “Mike D” Diamond of the American hip hop group Beastie Boys pose for a portrait with the President of Capitol Records Gary Gersh and a commemorative record for one million copies sold of the record “Check Your Head” circa January, 1993 in Los Angeles, California.

A couple of years after the hijinks of the “Ill” tour, the Beastie Boys released the ambitious, more rhythmically and lyrically complex album “Paul’s Boutique.” Yes, there was still plenty of mayhem, but critics were making noises that a certain level of maturity had, indeed, come a-calling.

The Beastie Boys referenced Jack Kerouac, Charles Dickens and J.D. Salinger; they came out against homelessness and racism. In “Three Minute Rule,” Yauch rapped, “A lot of parents like to think I’m a villain/I’m just chillin’, like Bob Dylan.”

In “Shadrach,” the Beastie Boys dug into Judaism for reference points. “We’re just three MCs and we’re on the go!” the Beasties rapped, basically renaming themselves after the Old Testament rebel heroes who refused to worship the golden calf.

In song, the Beasties went about their usual business — rappin’, boasting, sinnin’, eating hot-buttered popcorn, stealing from the rich, giving to the poor and, oh, givin’ a nod toward God. They sampled the chant of “Shadrach, Meschach and Abednego” from Sly Stone’s “Loose Booty.”

There were still plenty of naughty bits and insider jokes, but the Beasties were also coping with this badge of newfound respect. Yauch framed the Beasties’ sonic evolution in prosaic terms when we talked in 1989: “What we’ve been doing all along is making the music we felt like making,” he said. “We were just trying to say as much def stuff as we could.”

There were three more albums in the ’90s, “Check Your Head,” “Ill Communication” and “Hello Nasty.” The former went double platinum; the latter, triple platinum. And Yauch was continuing to look further and further outside himself.

In 1992, he trekked to Nepal where he met Tibetan refugees and started studying Buddhism and exploring the concepts of spirituality and tolerance. He co-founded the Free Tibet movement with Erin Potts and organized a concert to support it, which was recorded in a 1998 concert movie he executive produced.

It was directed by Sarah Pirozek and featured the Beastie Boys, alongside kindred spirits the Fugees, Beck, Alanis Morissette, Bjork, de la Soul and members of Sonic Youth, Rage Against the Machine, R.E.M., A Tribe Called Quest, Red Hot Chili Peppers and Smashing Pumpkins. And, of course, the Dalai Lama.

Previewing its 1998 screening in the Boston area, Yauch spoke with my then-Globe colleague Joan Anderman, telling her, “I think everybody learns as they live their lives. It’s a natural progression. I didn’t realize how much harm I was doing back then and I don’t think a lot of rap artists understand it now. I said a lot of stuff fooling around back then and I saw it do a lot of harm. I had kids coming up to me and going, ‘Yo, I listen to your records while I’m smoking [angel] dust.’ And I’d say, ‘Hey man, we were just kidding. I don’t smoke dust.’ People need to be aware of how they’re affecting people.

“In a lot of ways that early period, which was so overblown in the media, was just us joking around, almost mimicking a lifestyle. Maybe it went too far, because we became what we were mimicking.”

He spoke about the film — a benefit for the Milarepa Fund — the movement and his personal evolution. He had acquired a certain amount of idealism, and thought in his lifetime he would see a free Tibet “if people stay focused on it. Seeing the Berlin Wall go down, the end of apartheid are signs that that kind of change can happen.”

I reviewed the Beastie Boys at the Centrum, an arena in Worcester, Massachusetts, that same year. It was not tame, but it was not the devil-may-care free-for-all of yore, either. They didn’t sing “(You’ve Gotta) Fight for Your Right (To Party)” — maybe they thought it too juvenile or not an issue anymore (that your right to party was just assumed, not something to fight for). And the party was a little more responsible, with the Boys cutting the sexist blather of old and songs about getting “dusted.”

From the stage, Yauch praised Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi and dissed the U.S. bombings in Afghanistan and Sudan. “Terrorism will continue to escalate,” he said, condemning “racism in the Middle East toward Arabic people.”

He was greeted, mostly, with cheers.