The history of Jews and marijuana goes back a lot farther than you think

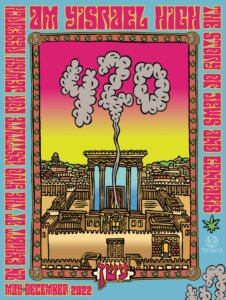

‘Am Yisrael High,’ an exhibit at YIVO, finds evidence of weed consumption all the way back in the Cairo geniza

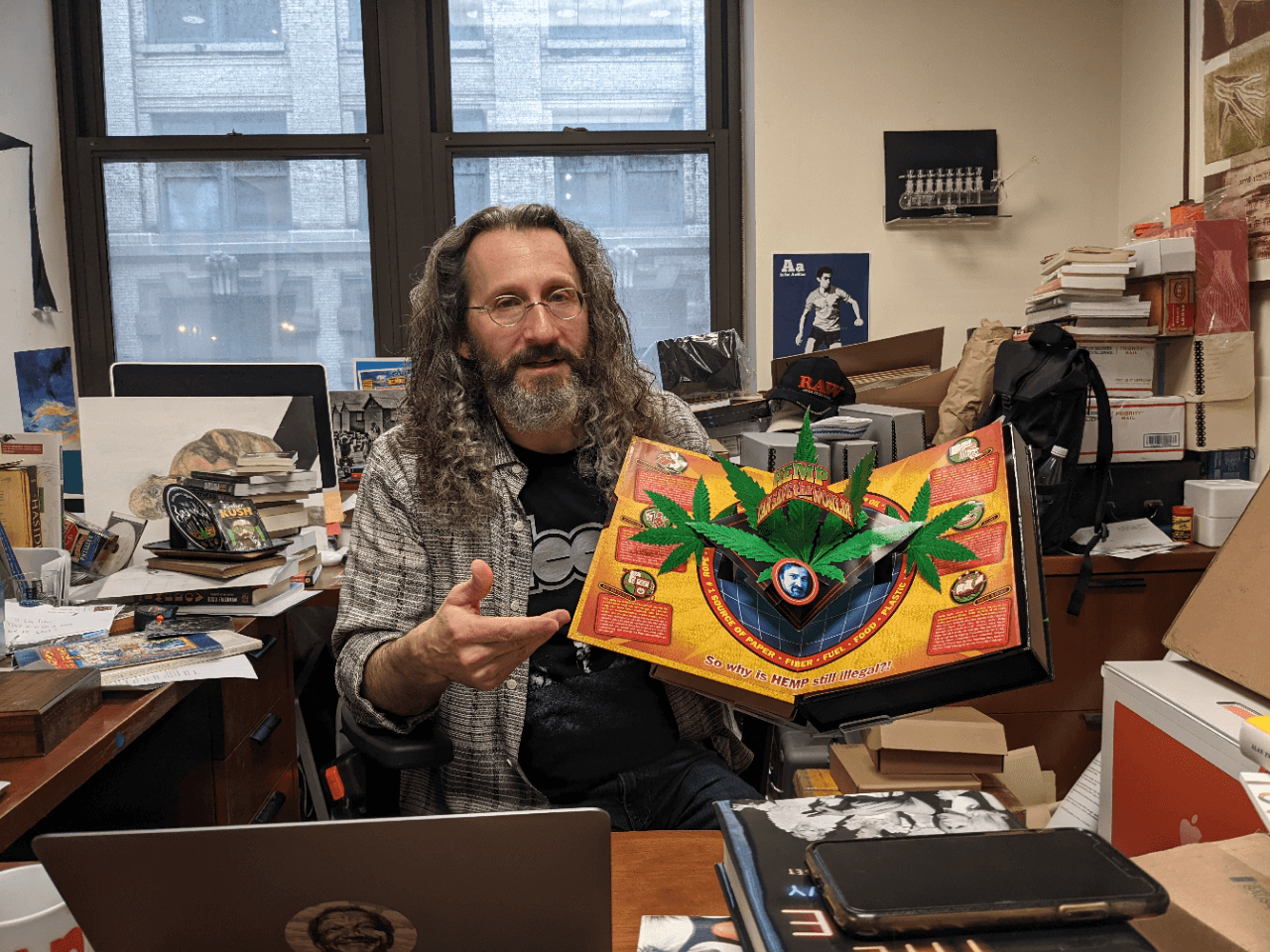

Eddy Portnoy is the curator of “Am Yisrael High: The Story of Jews and Cannabis,” Photo by Jon Kalish

The archive of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research contains 400,000 books, 250,000 photographs and millions of documents. Now, thanks to a new exhibit on Jews and cannabis, the archive has ingested a menorah bong and a box of Phillies blunts.

Need more evidence that YIVO has gone to pot? YIVO-branded rolling papers, stash jars and plastic joint-rolling trays are about to go on sale at the esteemed 97 year-old academic institution.

“It’s a whole YIVO dispensary,” quipped Eddy Portnoy, curator of “Am Yisrael High: The Story of Jews and Cannabis,” which opens Thursday night, May 5.

Portnoy would like the record to note that he did not test the bong because “you can’t smoke in the YIVO offices.” The box of Phillies blunts is actually empty. It’s in the exhibit because, as many a weed aficionado will tell you, the tobacco-leaf “wrapper” from the inexpensive cigar is used to roll a plump marijuana joint.

What most tokers don’t know is that the company that makes Phillies blunts began as Bayuk Cigars, Inc., a business started by three Jewish immigrant brothers named Bayuk, who set up shop in the City of Brotherly Love.

The exhibit opening will feature a panel discussion by Jews prominent in several areas of the current cannabis scene, including the leading cannabis horticulturist, a journalist who covers cannabis and a New Jersey rabbi/doctor/mohel who specializes in “cannabinoid therapeutics.”

Portnoy’s shoulder length locks may signal to some that he might be a stoner, but with a PhD. in Jewish history, but he is actually a widely respected scholar who specializes in Jewish popular culture. Whether or not he inhaled in the process, Portnoy did extensive research on the chosen people’s connection to the “evil weed.”

“There are so many Jews involved in cannabis that I could fill all the exhibit spaces in this building [with material on them],” Portnoy said as he led a visitor through the ground floor.

The YIVO administration apparently raised no objections to the acquisition of the bong and Phillies blunts box because, as an institution, YIVO has been collecting artifacts related to Jewish material culture since its inception in 1925. Referring to documentation that shows cannabis use in both religious ritual and the everyday social life of Jews in the Middle East going back two thousand of years, Portnoy observed, “This was a popular intoxicant, so Jews used it.”

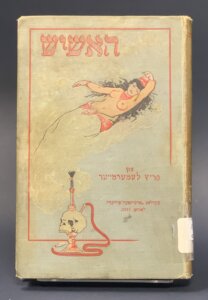

One of the most astounding items in the exhibit, as far as Portnoy is concerned, came from the treasure trove of papers discovered in the 19th Century in the Cairo Geniza, a storeroom containing holy texts, as well as quotidian pages awaiting burial.

Located in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Old Cairo, the Geniza’s contents have since been distributed to academic libraries in Europe, Russia and the U.S. Some of the documents are in a database created by the Princeton Geniza Lab, which has been digitizing the material for more than 30 years. In the Princeton database, Portnoy found lyrics to a song about wine and cannabis written by a man who frowned upon Jews high on hashish and their voracious appetites.

“It’s an early 15th Century reference to the munchies in Judeo-Arabic, said Portnoy. “That blew my mind!”

A further historical look back unearths the references to cannabis in the Talmud and Shulchan Aruch, where the plant is mentioned as a source for wicks to be used in the burning of sabbath lights. A 2020 report in an archaeology journal noted that limestone altars in the Negev were found to contain residues of burned frankincense and cannabinoids, including CBD, CBN and THC.

THC, of course, is teterahydrocannabinol, the compound in the cannabis plant responsible for the high. The first scientist to isolate it was an Israeli chemist named Raphael Mechoulam, who is about to turn 92.

Known as “the father of cannabis research,” Mechoulam isolated THC in late 1963 and early 1964. Working with colleagues abroad, he is credited with the discovery of the endo-cannabinoid system (ECS), a vast network of chemical signals and cellular receptors in humans that regulates many critical bodily functions, including learning, sleep, pain control and immune responses.

In the early 1960’s Mechoulam obtained hashish from the Israeli police for his research after an administrator at the Weizmann Institute assured a police official that Mechoulam was reliable.

“So the police invited me. I went there, drank a cup of coffee with a person who gave me five kilograms of hashish,” the chemist recalled. “I took the hashish on a bus and went back to the Weizmann Institute and started doing research on it.”

Although Mechoulam had given THC to monkeys and rats, he was eager to see its impact on humans. So, in 1964 he and seven other scientists at the institute did a small clinical experiment. Four of them took 10 milligrams of THC, while the other four were given a placebo. Mechoulam was one of the four who got the THC. It made him feel “a little bit high. I was just sitting around and feeling pretty well,” he told me.

The year before Mechoulam’s lab isolated THC, it fully unraveled the structure of cannabidiol or CBD, one of the 100 plus compounds in cannabis. CBD was originally isolated by scientists in the U.S. and the U.K. in the late 1930’s and early 1940’s. Today CBD is infused in everything from coffee to gummy bears. There were $6 billion in CBD sales in 2020. The market is projected to expand to $15 billion by 2024.

After reading historical references to cannabis being used for the treatment of epilepsy in the Middle East, Mechoulam’s lab collaborated with scientists in South America. In 1980 they gave CBD to 15 epileptic patients. The results, Mechoulam’s said, showed a marked reduction in seizures. This happened close to 40 years before the FDA approved Epidiolex, a pharmaceutical version of CBD, to treat pediatric epilepsy. That drug was developed by GW Pharmaceuticals, a British company, which cited Mechoulam’s 1980 study.

“I was delighted that somebody is ultimately using it,” Mechoulam said of the CBD drug’s regulatory approval.

The YIVO exhibit also acknowledges the Jews who figured prominently in the campaign to “legalize it!” One of the first public pro-pot demonstrations in the U.S. was led by the late poet Allen Ginsberg.

Another Jewish counter-culture figure involved in the effort is A.J. Weberman, the garbologist who gained 15 minutes of fame for going through Bob Dylan’s trash, though he seems to have limited recall of his own involvement in New York’s marijuana scene.

Portnoy was somewhat surprised to learn that Weberman knew about YIVO. The garbologist-turned-cosnpiracy-theorist spent time organizing the Jewish Defense League’s papers at the American Jewish Historical Society, which is in the Center for Jewish History building, also home to YIVO.

According to Portnoy, when he arrived at Weberman’s apartment, Weberman showed him artwork for a 1971 cartoon published in the East Village Other, a counter-cultural newspaper where he wrote a column that, among other things, advocated for legalization of marijuana. The cartoon had nothing to do with cannabis or Jews. It depicts President Richard Nixon being assassinated by someone saying, “Groucho sent me.” Published a few months after Nixon had declared his “war on drugs,” the cartoon was the work of the late Jewish cartoonist Yossarian— real name: Alan Shenker. It will be displayed at the YIVO exhibit.

Besides the cartoon, the exhibit also features an infamous quote from the 37th president. In May 1971, Nixon told his chief of staff Bob Haldeman: ”You know, it’s a funny thing, every one of the bastards that are out for legalizing marijuana is Jewish. What the Christ is the matter with the Jews, Bob? What is the matter with them? I suppose it is because most of them are psychiatrists.” The quote is embedded, along with an image of Nixon, on the plastic rolling trays YIVO will be selling.

If you’re planning to attend the May 7th Cannabis Parade and Rally in Manhattan, look for Weberman and also Aron Kay, better known as the “Yippie Pie Man.” Both Kay and Beal are scheduled to speak, along with two New York elected officials and a host of activists.

Portnoy said his 23 year-old son might attend but that his 20-year-old daughter will not because she has college finals. His kids have let it be known that the Jews and Cannabis exhibit is the first of their father’s 13 YIVO shows that really drew their interest.

When Portnoy asked a friend of his son if he knew about the late Jack Herer, the so called “Emperor of Hemp,” another Jew who played an important role in the mainstreaming of cannabis, the young man only knew that there was a pot strain named in Herer’s honor. Herer’s widow and son now run a company in Los Angeles that sells hemp and marijuana. An empty box of their pre-rolled joints will be displayed in the exhibit.

EZ Wider rolling papers are featured in the exhibit because one of the company’s two co-founders is a Jewish law school drop-out. Burton Rubin noticed that his weed-smoking peers tended to put two sheets of rolling paper together to create something wide enough for the purpose of rolling a “fat one.” Rubin looked at Department of Commerce records on imports and realized that the graph for rolling paper imports was almost a vertical line.

“I said, ‘There’s a business here,’” Rubin recalled.

Rubin said he started smoking pot in 1967 when he was a senior at NYU and has been consuming ever since. He had an inkling that weed would be legal some day when a cop showed up at his Greenwich Village apartment where a party was taking place and much inhaling was going on. As Rubin tells it, when he opened the door, a great burst of marijuana smoke escaped into the face of the NYPD officer who ignored it, saying only that there had been a complaint about loud music.

More than a half-century later Rubin marvels at the stickers with QR codes on the lampposts in his mid-town Manhattan neighborhood. The QR codes, when scanned, take you to a web site where marijuana is for sale. Rubin gets his weed shipped in a vacuum-sealed plastic bag from a western state where recreational marijuana is legal. It costs half the price of the pot for sale in New York, he said.

The grandson of a rabbi, Rubin considers himself more Buddhist than Jewish but many of his efforts since selling the company that makes EZ Wider rolling papers are very Jewish. After the $6.2 million sale in 1980, he planted a thousand trees in Israel, bought a Torah for his parents synagogue in Monroe, N.Y. and sent his folks on a trip to Israel. Oh, and for 15 years he prepared meals for homeless people at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

Manhattan-based radio journalist Jon Kalish has reported and recorded for NPR since 1980.