How I discovered a connection to my mother that I never expected to find

He knew his mother survived the Vilna Ghetto, but a trip to Belgium taught the author a good deal more

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

James Baldwin wrote that when you go on a journey “you cannot know what you will discover, what you will do, what you will find, or what it will do to you.”

In 2003 I set off on what seemed a fairly clear-cut research trip to Brussels, where my parents had lived and worked for five years after surviving German concentration camps. I was convinced I could write a book about their lives there, with my mother’s life in the foreground since she had resumed teaching. What I found and brought home with me was something very different — and far more valuable.

She’d been dead for four years at that point, but my witty, multilingual, fiendishly well-read mother loomed in my mind with the grace and gravitas of Daniel Chester French’s Alma Mater statue at Columbia University.

A filtered version of my mother had appeared in many different ways in various novels and short stories I’d published over the years, but when she died in 1999, I felt compelled to devote a whole book to the remarkable Belgian period in her life and pay tribute to the actual woman she was.

My mother was born in Russia but grew up in Poland, where she survived the Vilna Ghetto and several concentration camps. After escaping from a German slave labor camp near the end of World War II, she met my father in a displaced persons camp, and soon afterwards settled into a new life in Brussels.

Before the war, she had taught piano lessons. Now she was teaching Yiddish language and culture in a school for Jewish children who had been hidden from the Nazis, many of them in convents and monasteries. They had to be reintroduced to the culture from which they had been cut off for years.

It seemed like a story that had rich possibilities, and in 2000, as I reached out on the internet, I found her favorite pupil, Floris, living in Melbourne.

Floris helped me make contact with the daughter of the school’s head teacher, who herself sent me a list of my mother’s other students. I brushed up on the French I’d studied for eight years, which I’d further polished on numerous trips to France, and arranged to meet Floris when she next planned to be in Brussels, a city my parents had adored. I also contacted some of my mother’s other students in hopes of learning more.

It was an eye-opening week in Brussels. My mother’s past came to me in a completely different version than the one I’d known. Now I saw her through the eyes of elderly women and men looking back at themselves as children and seeing my mother as a young Holocaust survivor who somehow avait du chien — she was chic.

Floris and I visited the Jewish Museum in Brussels, a lavish turn-of-the-century townhouse which had photo albums of the group of survivors my mother was part of. Perusing them, I realized that after everything she had endured, she was somehow, almost inconceivably, still truly elegant.

But more importantly than that, she was an enthusiastic teacher, and her former students told me she would sometimes hug herself with delight when presenting material in class she found exciting. “So that’s where I got my love of teaching from,” I thought.

Floris was in her 60s, with bowl cut salt-and-pepper hair, a stocky, solid woman with no trace about her of the brooding teenage sylph I’d seen in photos.

“You’re not what I expected,” she said more than once. “I thought you’d be bald and fat and professorial.”

“Well, I might be — someday.”

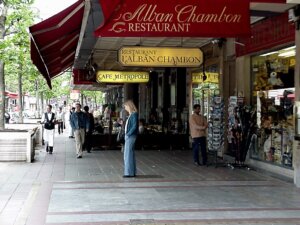

Each night as I sat and made notes in the café of the dazzling Art Nouveau Hotel Métropole, it seemed strange to contemplate my mother as a young Holocaust survivor rebuilding a life from nothing.

The lavish decor of the hotel felt like a promise: my book would be just as sumptuous. I took endless photographs and made notes in English and in French. I paid to have the archives of the Jewish school indexed and forwarded to me. When I actually received the index, however, it was disappointing. My mother’s role was too short-lived. And traces of the play she had written, produced, and taken to London to perform existed only in a series of photographs of students on stage and my mother standing backstage looking anxious and dramatic, one fist tightly clenched.

For some reason, Floris put me in touch with a diminutive bald baron in his 70s who had been active in the Resistance, and while telling me his own story, which I dutifully recorded, he took me to a series of famous bars and taverns. I learned that every single Belgian beer has its own unique style of glass and that a common snack with beer is bread with cream cheese and sliced radishes. It seemed unlikely but it was delicious.

He spoke no English and strained my French to the limit — or improved it, actually. He certainly made the hotel staff look at me with more respect when he asked them to call up to my room, where they told me with a note of surprise that “Monsieur Le Baron Halter vous attend” (Baron Halter is waiting for you).

But the next morning, I had no idea what I could do with the narrative he’d shared.

That week in Brussels, I interviewed and recorded Floris extensively about what it had been like being in hiding as a child and what that meant to her years later. It seemed like a natural part of the potential book.

Those years were traumatic, especially when a host family forced her to go to Mass. Her dark stories hovered over our café tables no matter how sunny the day.

I also spent time with a Francophone friend I’d first met at a conference in Israel. Her English was minimal, which was good for my French, and I felt steeped in language, culture, history, possibility. Time and again, I thought I caught glimpses of the book I yearned to write.

But even back home, after doggedly contacting people in the U.S. and Canada who had known my mother during those Belgian years, the book about her eluded me. I had file folders filled with all sorts of mismatched notes, sketches, memos, and photographs that seemed never to coalesce and would never make anything like a book. I had spent so much money on my hotel and flight, invested so much emotion, and couldn’t quite fathom how I’d ended up without so little to show for it.

Nevertheless, I took away something inestimably precious from that unexpected week in Brussels: All of her former students said that I had my mother’s smile.

This made me cry every time I thought of it. Growing up, I’d always been told that I looked like my father, not my mother, and to receive this particular recognition after her death somehow brought me even closer to her. No one back home had ever said that to me before.

So when I went to Belgium, I didn’t find material for a book, but I found a new connection with my mother that’s never been broken.

I also fell in love with Belgian beers and have a growing collection of glasses to serve them in. Each one reminds me of the journey with an unexpected discovery, and of my mother, though I never saw her drink a beer in her life.

Lev Raphael is the author of 27 published books including the memoir “My Germany.”