Larry King wasn’t the only big shot from Bensonhurst

The author recalls the early days of the Warriors and his father Herbie Cohen, the world’s greatest negotiator

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

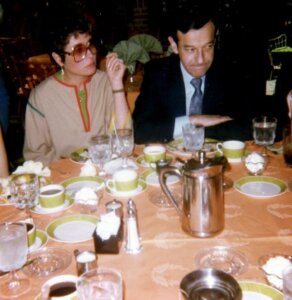

Long before he wrote the book You Can Negotiate Anything, worked for the Carter and Reagan Administrations, served on the START talks, or even married my mother, Herb Cohen, known to friends as Herbie, was a member of a gang of young Bensonhurst roustabouts called the Warriors.

Every member of the Warriors, most of whom were born in the early 1930s, had a nickname. There was Inky, Sheppo, Ben the Worrier and Gutter Rat, who was supposedly called Gutter Rat even by his own mother, as in, “Gutter Rat! Dinner!” There was Moppo and Bucko. There was Who Ha – real name Bernie Horowitz — called that because, one night, having been asked a question, he said, “Who?,” then, when the question was repeated, he said, “Ha?” There was Zeke the Creek the Mouth Piece – real name Larry Zeiger, later changed to Larry King – called that because even then he was always announcing. My father insists he was called Handsomo (“Because I was so good looking,”) though I never believed him.

Attendance at gang functions began to decline in the early 1950s as even the most devout Warriors went off to work, college, or the military. From there, they scattered across the city and country, became parents, then grandparents, and lived their lives. Then, starting in the early 2000s, as the Warriors entered their eighth decade, a strange thing happened: they began to reconvene, only instead of Bay Parkway and 86th Street, it was Southern Florida, an area of the world my father has always identified as the true promised land of the Jews.

After living in Brooklyn, Long Island, New Jersey, Libertyville and Glencoe, Illinois, and Washington D.C. — – a new house or apartment in each town, a new street with new friends and new habits – my parents found themselves in a palm-shaded home just off the third fairway of the Boca Delray Country Club. There was a player piano in the living room, a bathroom walled with mirrors – you could see parts of your body you’d never even imagined – a screened in pool where shanked tee shots drummed down like hail.

Several other old Warriors – excluding Larry King, who’d married again and was living in L.A. – were vegetating in nearby communities with opulent names. The Three Seasons. The Shangra Shalom. The Heavenly Heathen. Herbie and Ellen began gathering with these aging Brooklynites in the afternoons in this or that house or condo. They’d known most of these people since grade school. They had been in junior high school together when Japan surrendered. They had lived through all of it. Cold War. Nuclear terror. Nixon and Clinton. The collapse of the Berlin Wall. Being a little old for rock n roll, they had stayed with the classics – Sinatra, Nat King Cole. When I asked Herbie how he’d missed the Beatles – he was 30 when they appeared on Ed Sullivan – he said, “I was working.” They had seen American at its apex, had seen the boom and what appears to be the decline.

There were usually five or six old Warriors at these get togethers, some of whom I’d known all my life, some of whom I’d known only from stories. Who Ha, who was still married to his first love Honey and still described himself as a “manufacturer’s representative;” Inky, who’d been only the second white student to attend Howard University Dental School; Arnie Perlmutter, who was short with freakishly long arms, which, according to Herbie, “is what made him such a devastating softball pitcher;” Brazzy Abatti, who never recovered from some of Herbie’s teenage antics – Google “The Moppo Story” — was a brain surgeon with practices in Ashville, North Carolina and Beijing, China; Marty Lefko, the great athlete of the gang – he played division one college basketball, who worked for IBM; Bucko, whose real name I never did learn, had been an Army MP in Korea, a mob runner, a grifter and a stock car racer, a legend on the dirt ovals of the Southeast, then a real estate broker.

It seemed funny that, no matter what these men had done or achieved in their lives, they ended up in the same place, drinking the same wine on the same marble floors. (Nothing poses a greater threat to the elderly than wet marble). One of the wives had t-shirts made up for the men (“Aging Warrior”) and for the women (“Aging Warriors Ladies Auxiliary.”)

I loved going to their events, listening to the small talk and stories. Once, when Arnie was trying to remember where he’d played YMCA basketball, he turned to Marty and said, “Hey Marty. Do you remember that Turkish place where we had dinner a few years ago in the city? You got a stomachache and had to leave early. Do you remember the address?”

“Yeah, I remember,” said Marty. “It was on 10th Street and 2nd Avenue. Only it wasn’t a stomachache, you schmuck! It was a heart attack! Remember the large white square vehicle with flashing lights that took me away?”

My mother enjoyed these get togethers, then didn’t. “It’s depressing,”” she told me. “Every time we go, they tell us someone else is dead.”

The last time they gathered as a group was at Marty Lefko’s funeral. The Rabbi, who had not known any of the Warriors, eulogized Marty in the generic way of a clergyman working off someone’s else’s notes. He said Marty had been a member of a gang called the Warriors, which had a clubroom in the basement of a house owned by Larry King.

Who Ha shouted when the Rabbi said this: “Bullshit! That was my house. Larry had no fucking house. Larry lived in an apartment.”

Herbie shushed Who Ha, who snapped at him, saying, “No, I won’t shush. Larry got famous, so what? Does that mean everything that happened to me gets attributed to him?”

“Hey, Bernie, who gives a fuck about your house,” said Herbie. “Let’s remember why we’re here. See that box up there? Our friend Marty is in that fucking box.”

Larry’s fame had long been a distraction. To most of the Warriors, it was exciting in the way the success of Sandy Koufax, another neighborhood kid, had been. It connected them to the upper world. It put the landscape of their childhood on the map. But Who Ha hated it. Every mention of Larry – “Did you grow up with Larry King?” “Did you know Larry King before he was famous?” – felt like Zeek the Creek the Mouthpiece giving him the high hat. When Herbie and Larry arrived together at a reunion in a hired car, Who Ha went wild. “What? You think you’re special because you got a limo? I can get a limo here in ten minutes. Let me make a call and I’ll have a limo and I’ll be a big shot, too.” Who Ha made the call. When the Warriors stumbled out at midnight, Who Ha’s car was waiting. “Now, I’m a big shot too!” he shouted.

Excerpted from THE ADVENTURES OF HERBIE COHEN: World’s Greatest Negotiator by Rich Cohen. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2022 by Rich Cohen. All rights reserved.