Why a seemingly unconventional casting choice makes perfect sense in a story of Holocaust survival

A father explains how his son’s role gives added depth and resonance to Karen Hartman’s ‘The Lucky Star’

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

I am not Jewish, and my son, Sky Smith, is ethnically half-Japanese, so it was surprising to see him onstage playing the grandson of a Holocaust survivor, berating his Jewish father for putting a soft focus on the horrors of the past. It was more surprising still because my son’s character in the play carries my distinctly Gaelic given name, Craig.

What was Karen Hartman, the playwright, up to? Her play, “The Lucky Star,” has brought me to tears each time I’ve seen it – not because my son is in it, but because of the layers of loss that pile up as the play progresses; lost happiness, lost dreams, lost potential and, of course, lost lives.

Yet the play is about much more than loss, and much more than the Holocaust. It is about the diligence required to resist the mutability of history. It is about how so much history is hidden from us, and how hidden history can resurface in unexpected ways. It is about how history is not one thing but is rather a mesh of interconnected tendrils ever growing beneath the surface, linking us all.

When my son was 12, I took him on a reporting trip to Krakow. I was doing a story on the revival of Jewish culture in Poland, anchored by an annual Jewish festival there. The eventual headline said it all: “In Poland, a Jewish Revival Thrives — Minus Jews.”

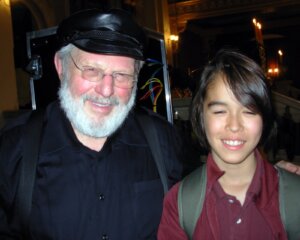

But, in fact, there were some Jews there – a small minority, many hosted by the Taube Foundation for Jewish Life and Culture, which had invited me there – and so my son spent the days in Krakow learning to sing Hasidic nigunim, listening to Klezmer bands, eating latkes and getting a crash course on the Holocaust. We visited Auschwitz with the children of survivors. He met Theodore Bikel.

So, it was a surprise to hear, 15 years later, that he had been cast in a play about a Jewish family trapped in Krakow during the Nazi occupation. It had nothing to do with his earlier visit – in fact, the casting director didn’t even know he had been to Krakow until I mentioned it at the show’s premiere. But why did they cast a half-Asian man to play a Jewish son?

Holocaust narratives have hardened into well-known archetypes, clustered like megaliths that inspire awe but are increasingly impenetrable. As a character says in the play, “the Holocaust was memory, and when I wasn’t looking it turned into history.”

That history is suddenly, sadly, relevant again. Middle-class families, some Jewish, are again risking their lives to escape war in Europe – oddly, many fleeing to Poland. And who could have imagined just a few years ago that the U.S. would witness on its own soil a torchlit march of young neofascists chanting, “Jews will not replace us.”

For some, of course, none of this is unimaginable. My brother-in-law is the son of Holocaust survivors – another tendril of history that intertwines with mine. His parents came out of the camps in Poland, scarred mentally if not physically. He sees the world less securely than I do. At one time he owned a gun, though he is a gentle intellectual. Having grown up with the ghosts of calamity, he lives with a survivalist bent.

What the playwright, Hartman, does by casting a half-Asian man in this deeply Jewish story is lift the Holocaust narrative out of the traditional Ashkenazi context, breaking the megalith into pieces that more people can relate to and understand. No explanation is given – and only insiders know that a wedding portrait on one set of the play shows an Asian bride.

“I believe in casting as part of the interpretation of the story, and part of how a story reaches its moment,” Hartman told me when I called her. “I think it’s important to ask that question when you’re casting something: ‘How has the moment changed?’”

Questions of continuity and inclusion are very much alive in the Jewish community right now, she added. Statistics show that the percentage of nonwhite Jews, particularly in the U.S., is on the rise.

Hartman said she asked her collaborators, “What would happen if the person who is really carrying the torch of history is cast as a Jewish person of color?” She noted that a close collaborator on a different project is half-Chinese, half-Jewish, and the descendant of Holocaust survivors, yet he rarely sees people like himself in Jewish stories.

So, my son got the job.

And the name Craig? There, Hartman was true to the book on which the play was based, written by a former journalist, Richard Hollander, who discovered a briefcase of letters after his father died. The letters turned out to be the most significant correspondence to survive the Krakow Ghetto. I asked Richard why he gave his son a name so far from the Jewish tradition. He said his son was named after Richard’s maternal grandfather, whose Hebrew name was Chaim and Anglicized to Herman. “We took the “C” from Chaim and named him Craig,” Richard said, adding, “we chose very pedestrian names for our children.”

Broadway veteran Steven Skybell, renowned for his portrayal of Tevye in Joel Grey’s Yiddish-language production of “Fiddler on the Roof,” leads the cast with a deep and complex performance of Richard as a kind of impermeable, genial Holocaust salesman whose shell cracks in the second half.

In the play, my son’s character is a historian specializing in African slave narratives – as the real Craig Hollander in fact is — increasing the show’s resonance further to include what is often called the Black Holocaust. Indeed, as unique as the Holocaust was in modern history, genocide is not. Hate is everywhere, like a prairie fire racing too fast to stamp out. But love is there, too.

Director Noah Himmelstein’s deft, invisible hand builds a play about a family that feels like yours or mine, in my case rather literally. It drew me back to photos of my much younger son on our trip to Krakow, and Mr. Himmelstein uses photos to stage an accessible, if heartbreaking, universally effective ending. As the names of the characters are read aloud, the audience sees black-and-white photos of the real people who did not survive, paired with color videos of the sole survivor’s grandchildren who now bear their names.

“The Lucky Star” plays through June 12 at 59E59 Theaters.

Craig S. Smith is a former reporter for The New York Times.