Breaking the silence on the pogroms in Ukraine

Lisa Brahin recounts a harrowing family story, replete with inspiring heroism and unimaginable cruelty

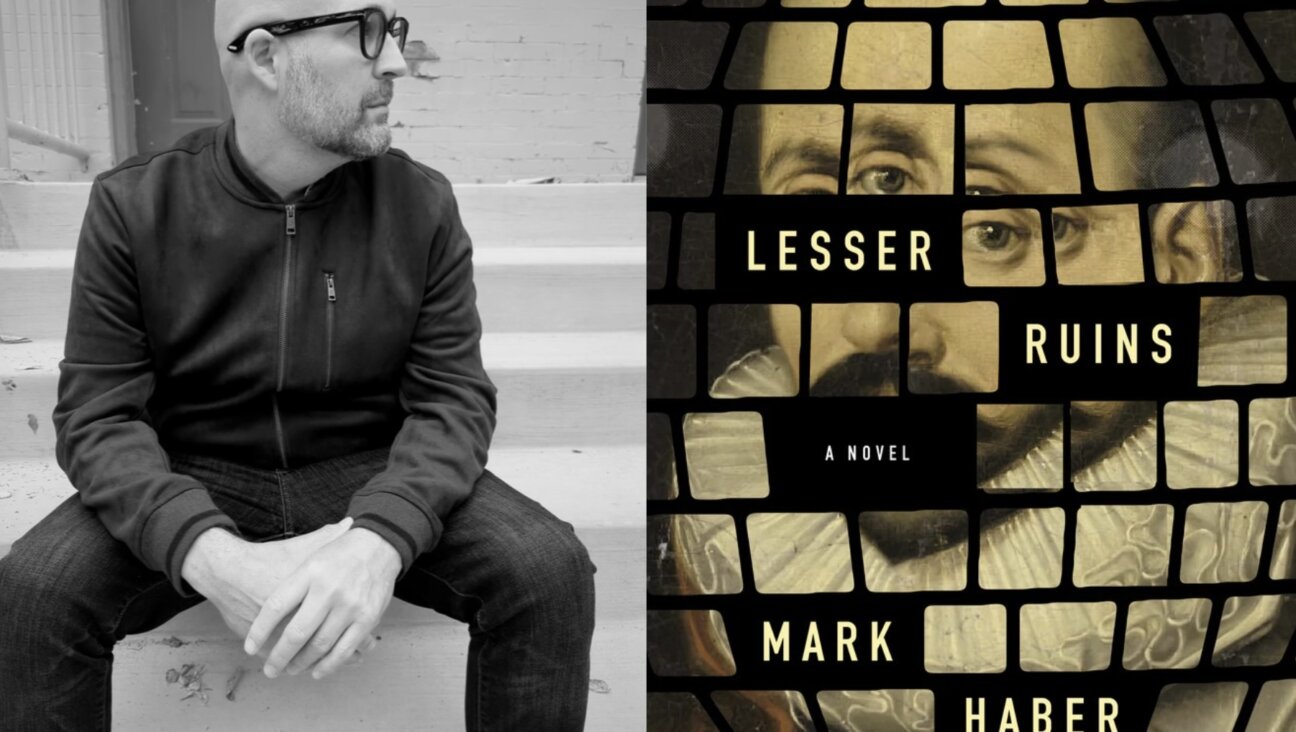

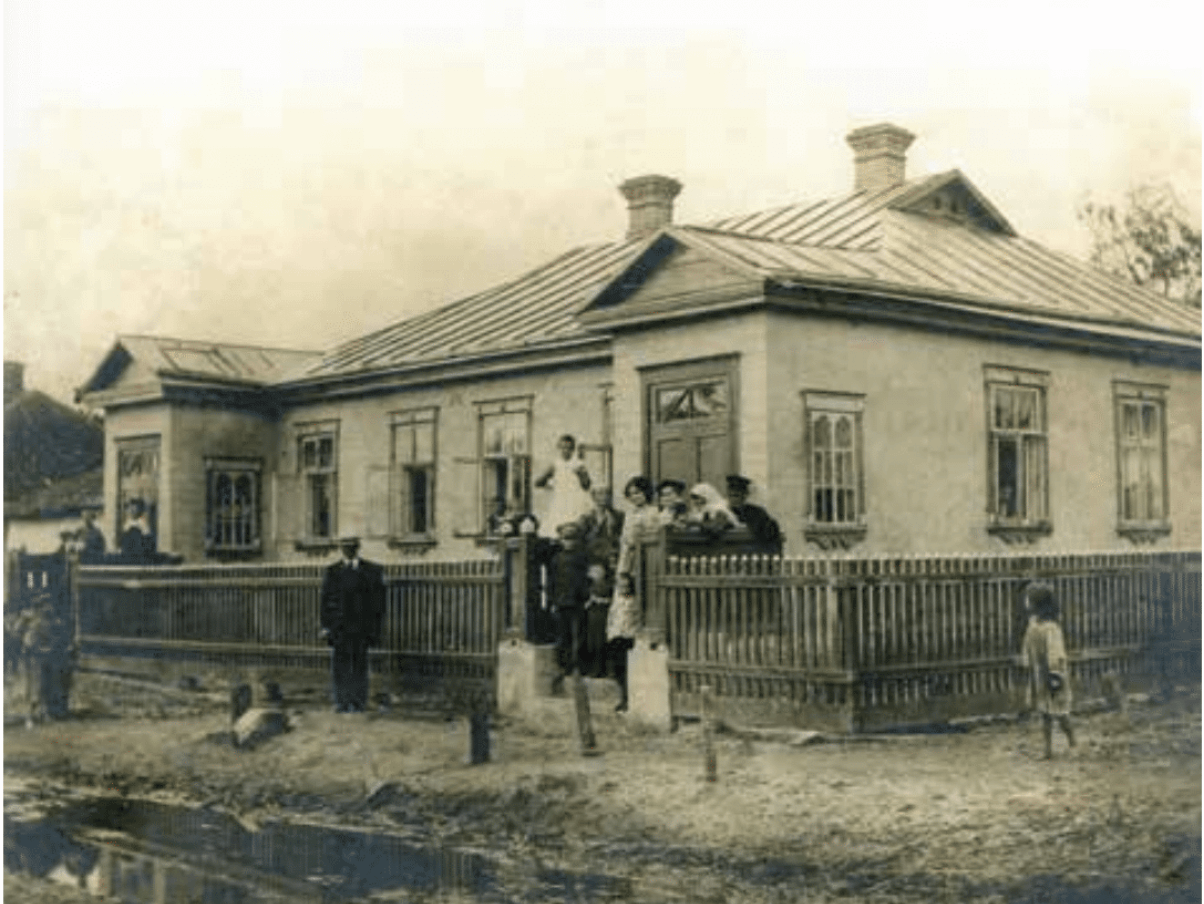

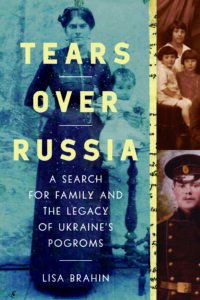

Itzie Stumacher’s house in Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine, 1911, which was featured in Lisa Brahin’s “Tears Over Russia.” The second door was a rental apartment where the Caprove and Cutler families stayed after fleeing Stavishche during a 1919 pogrom. Courtesy of Marsha Kaufman

Tears Over Russia: A Search for Family and the Legacy of Ukraine’s Pogroms

By Lisa Brahin

Pegasus Books, 310 pages, $28.95

Ukrainian history is steeped in violence and tragedy. Long before the recent Russian invasion, Ukraine was part of what Yale historian Timothy Snyder has called “the Bloodlands” — the swath of Central and Eastern Europe where Hitler and Stalin’s clashing forces murdered millions of noncombatants. In Ukraine alone, more than a million Jews were slaughtered by Nazi killing squads, often assisted by the local population, in the so-called Holocaust by bullets.

But decades before it became a Holocaust killing field, Ukraine was the site of genocidal pogroms in which hundreds of thousands of Jews were murdered. The deadliest massacres occurred between 1917 and 1921, during the Russian Civil War. That violence impelled a mass flight from the country, with many emigrants ending up in the United States. Author Lisa Brahin’s ancestors were among them.

The impact of the pogroms has been muted to some extent by the even more powerful trauma of the Holocaust — and by the overwhelming desire of many survivors to move on and embrace their new American lives. Brahin, a Jewish genealogist and researcher, confronts that silence in her family history, “Tears Over Russia.”

Starting with her grandmother’s recollections, she has produced a remarkably vivid account of life in the Old Country that reads at times like a novel — or a series of Sholem Aleichem stories — with matchmakers racking up both triumphs and disasters and marauding thugs imperiling Jewish villagers.

The parallels are deliberate. A wedding in her family’s hometown of Stavishche, Brahin writes, “resembled a scene that one might find in a Sholem Aleichem story,” where joy, like sorrow, was often collective. “When someone laughed,” she writes, “the whole town laughed.” As it happens, the famous folklorist himself had a connection to Stavishche through his wife’s family.

Aspects of “Tears Over Russia” have a mythic quality, with larger-than-life characters surmounting impossible circumstances. The town rabbi, Rabbi Pitsie Avram, cousin to Israeli politician and military leader Moshe Dayan, was “a brave, charismatic, and effective negotiator” whose gutsiness — admired by bandit leaders — saved many Jewish lives. Brahin’s cousin-by-marriage Barney Stumacher was equally resourceful and courageous, enduring fantastical adventures to rescue friends and family in Ukraine.

The book’s initial inspiration, Brahin tells us, was a sepia-toned photograph of her great-grandmother, Rebecca Cutler Caprove, with her baby, Channa. A glimpse of another world that Brahin waited decades to pursue, it now graces the book’s cover.

At the core of the narrative is a series of interviews Brahin conducted with Channa (Americanized to “Anne”), who lived from 1912 to 2003. Brahin supplemented those interviews with extensive research, aided by the internet, that led her to both rare documents and witnesses.

The riveting prologue is a seemingly miraculous account of survival during a June 1919 pogrom. Brahin’s great-grandparents, Rebecca and Isaac, with no time to return to their house, hid from rampaging thugs in the cellar of an inn. They feared the worst for their two children, sleeping at home. But Channa and her sister, Sunny, were left unmolested. It’s a version of the Passover story that owes its happy ending to the family’s past kindness to one of the pogrom’s peasant leaders.

Brahin delves deep into family history, recounting her great-grandparents’ tumultuous on-and-off romance. After their 1911 marriage, Isaac Caprove was drafted into the Russian army, missing the birth of his first child, Channa. Meanwhile, the political situation grew increasingly dire, with rising antisemitism and the start of World War I.

One of Channa’s happiest childhood memories was of picking flowers on the estate of Count Władysław Branicki, a nobleman of Polish origins who opened his grounds to town residents. His estate was among the first targets of violence in 1917. The Jewish population of the region would be next.

Brahin has incorporated startlingly precise eyewitness accounts of bandits — some of them “local priests, landowners, students, teachers and peasants” — not just looting and destroying homes, but beating, torturing, raping and murdering their Jewish neighbors. It’s horrifying and all but inexplicable, prefiguring the even larger-scale killings of the Holocaust.

The quest of Barney Stumacher, a World War I veteran who emigrated to the United States in 1911, to rescue his relatives is the book’s most compelling thread. After receiving a heart-wrenching letter from his father in 1920, he leaves the safety of his New York City home and returns to Ukraine to find his parents, three sisters and others.

From Bessarabia (now mostly Moldavia), he sneaks into Ukraine just as virtually every other Jew is trying to flee. Soldiers there confiscate everything he’s carrying: money, cigarettes, food. Then bandits steal his shoes.

He gets some help from the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee before managing to board a freight train in advance of Polish troops. But their gunfire causes a derailment, and Stumacher helps pull other passengers to safety. He and an acquaintance purloin horses to continue their journey. At another train station, he is arrested by Communist troops, but one sympathetic Jewish soldier gives him false papers that help him, once again, slip away.

In the end, Stumacher guides almost 80 people, including Brahin’s family, on a wagon train toward the border. Their escape is harrowing. Brahin’s family almost drowns while crossing the Dniester River by rowboat. Stumacher and one of his sisters are arrested for possessing false Romanian passports. And Brahin’s family must weather a three-year layover in Romania while awaiting U.S. visas.

Then, finally: a perilous crossing to the Golden Land. After a stint with relatives in Massachusetts, the Caproves move to Brooklyn and, later, Philadelphia. Channa — now Anne — leaves school at 14 to work full-time in a garment factory. She is plagued by persistent claustrophobia, the traumatic fallout of hiding in crawlspaces during pogroms.

Mostly, though, her American story is a happy one. She wins beauty contests, becomes a table tennis champion, and enjoys a 66-year marriage that produces a daughter, Marcy. And a granddaughter, Lisa Brahin, who makes sense — whatever sense is possible — of a life marked by terrifying trials and ultimate survival.