The day no one wanted Elvis — but my grandfather

In January 1956, just before the King became a national sensation, Papa Fred had an exclusive chat with him

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

I knew that my grandfather interviewed Elvis. But until recently, that’s about all I knew.

When Ad Age published an obituary for its former editor Fred Danzig (whom I called Papa Fred), it said he was the first entertainment reporter to interview Presley. Growing up I heard Papa Fred was the first East Coast reporter to interview Elvis, which, given my grandfather’s care for the facts, seems more likely.

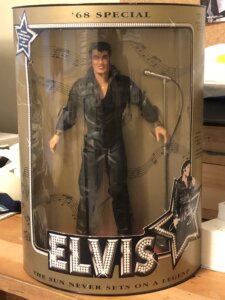

That the two met — twice, I would come to learn — was more than just family lore, like the fact Barbara Bush was Papa Fred’s classmate. Elvis’ presence could be felt. I remember finding the afikoman in the same room as a shrine to the King: a glass-doored display cabinet with a decorative plate and an unboxed doll of Presley in the black leather jumpsuit from his ‘68 comeback special.

I have the doll now. I asked for it one day and my grandparents, as was their fashion with anything they owned, gave it to me the moment I expressed an interest. Apparently this took some wearing down. My older sister, who met no resistance asking for our grandparents’ upright piano, wanted Elvis first; it was the only time she heard “no” from Papa Fred.

I really had no right to the doll. I didn’t know the first thing about Elvis and what little I did probably came from my asking about this bizarre toy, so unlike anything else in the house, whose décor otherwise constitutes tasteful reproductions of classic paintings, books and – in the kitsch department – a matryoshka doll of the Glasnost-era Politburo. Jews were not meant to have household shrines and idols before their God. Elvis was an evident exception. My grandmother Edith called Papa Fred’s interest in the rock star a “fixation.”

I never really spoke with Papa Fred about Elvis. Or really any music for that matter. I knew he liked Benny Goodman and Louis Armstrong, and that he watched “American Idol” long after much of the public lost interest. I remember him absentmindedly singing “doobie-doobie-doo” as he drove, so Sinatra was on his radar. His record collection, still at the house in Eastchester, New York, where my mother grew up and where Edith still lives, includes some Sergio Mendes, Charlie Parker, Ella Fitzgerald and instrumental compilations. He has a couple albums by jazz trumpeter Neal Hefti (Papa Fred wrote liner notes for one of them when it was released on CD), the requisite show tunes and a Henny Youngman LP.

But as my mother says, they were a decidedly “non-musical family.” That Papa Fred ended up writing four music columns a week for United Press International was something of a fluke.

Papa Fred’s love of Elvis didn’t quite make sense on its own terms. I long chalked it up to loyalty, or respect for a gentlemanly 21-year-old he met when he himself was just 30.

Elvis “was a very polite young man,” he always told my mother.

I figured Papa Fred probably liked Elvis for the same reason he liked the Dallas Cowboys, despite the fact that he’d lived nearly his entire life — minus some time in Army training and the European Theater — in New York: He experienced a rising phenomenon firsthand, saw how it changed the game and became a lifelong fan.

But when I did some digging I found there was more to Papa Fred’s admiration. He always showed up for Elvis, because when they met, no one else did.

When they crossed paths on Jan. 31, 1956, my grandfather was the only reporter in New York who bothered to pay a visit to the RCA studios on East 24th Street, where Elvis was on his second day of recording what would become his self-titled debut album. Despite a publicity blitz, Papa Fred had the singer’s full attention between sessions, and sat down with him for around a half-hour. Peter Guralnick’s 1994 Elvis biography, “Last Train to Memphis,” goes over the details of their discussion in about two pages.

As Papa Fred told Guralnick, he knew about Elvis courtesy of Marion Keisker, a radio host and station manager who was the first person to record Presley and the one who brought him to his first label, Sun Records. Papa Fred’s work with United Press also had him polling over 700 DJs for their favorite artists in each genre. While the airwaves in New York had yet to hear the rich baritone of the boy from Tupelo, Presley, who had by then had a few charting singles for Sun and performed on a TV show called “Louisiana Hayride,” came in at a respectable ninth place on the National Disc Jockey Poll’s Country-Western list.

So, when Elvis came to New York in early 1956 — unprepared for the cold weather and appreciative that, unlike the women in the South, the girls there didn’t swarm his Cadillac — Papa Fred was already briefed on all the fuss. Even if, in the North, there wasn’t any yet.

“You’re the first interview for Elvis,” an RCA Victor publicist, Anne Fulchino, told him, according to a 1959 article Papa Fred wrote for a fan magazine, three years after his tête-à-tête with Presley. “Nobody wants him. Nobody but you.”

The existence of this article, the manuscript of which Guralnick draws from in his book, was news to everyone in our family. It is a remarkable document of a young star on the cusp of a supernova. The 21-year-old Elvis, observed by a reporter up close for perhaps the first time, has a moist handshake, chews his fingernails, speaks softly and tells his interviewer about his plans to buy his parents a house: “If I ever thought that what I was doing was making them unhappy, I’d quit in a minute,” he said. (Somewhat paternalistically, at the mention of James Dean, Papa Fred took the opportunity to ask Elvis if the actor’s recent death in a car crash had changed the way he drove — it had.)

This was the first time Papa Fred met Elvis, but not the first time he saw him in action. That was the week before, when Elvis made his national TV debut on “Stage Show,” a variety program hosted by Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey.

“I felt he had what the show business impresarios call ‘It,’” Papa Fred wrote of the broadcast. “His voice had a certain bluesy, back-home quality that was reminiscent of the great, rhythm-driving folk singers of the South. His gyrations? Well, they certainly put the audience into a swinging, happy mood. Some of it, I felt, looked put on, overdone. But there was no denying that he handled those hips and legs masterfully, the way a Stokowski works the hands.” (Stokowski was a conductor.)

When Papa Fred sat down with Elvis in the control room at RCA, away from the band, he asked the kid just how much of this scandalous legwork was affected.

“I don’t know how to answer that,” Elvis said. “I just remember that one day I was singing and rocking along real good and I heard everyone out front screaming and I wondered what it was they were screaming about. I looked down and saw my legs shaking like crazy and I figured if my legs were gonna shake, and they were gonna yell and carry on, why, I couldn’t help either.”

You can’t read this without seeing just how young — and un-media-savvy — Elvis is, or anticipating how soon this guileless kid would gain perhaps the highest profile on the planet.

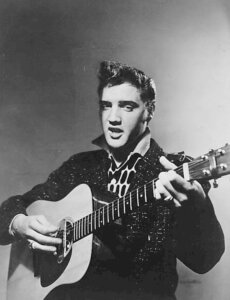

And about that profile: Papa Fred marveled at it. “His long, dark brown hair was shiny, silken, well-trained. His skin was remarkable: a creamy texture that appeared immune against whiskers … I would say it was his eyes, more than the sideburns or anything, that held my attention. They had a softness and yet they were intense. They were lonely, friendly, kind.”

His face reminded Papa Fred of a marble statue of Apollo in the Olympia Museum — he later told Guralnick his features all came together to form “a god.”

The musicianship takes up less space in this account. The report briefly touches on the artists Elvis admired — named are the Black group the Ink Spots — but gives more inches to why Elvis had a leather cover for his guitar: His belt buckle would scuff it otherwise.

Speaking with Papa Fred, Guralnick was able to uncover a little more. At 21, Elvis spoke frankly about his foundational Black influences. He lay awake at night listening to blues singers on the radio and emphasized the importance of gospel.

“I was very surprised to hear him talk so knowledgeably about Black performers down there and about how he tried to carry on their music,” Papa Fred told Guralnick in the 1990s, when Presley’s debt to Black music was much on people’s minds.

The initial dispatch Papa Fred wrote off this encounter was less revealing than what he’d write for the fan magazine years later, when everyone wanted to know about Elvis’ scuffed alligator loafers or the early reception of his sideburns at RCA.

“The name Elvis Presley, when spoken aloud, reminds some of a steam engine about to go tearing up a track,” the UPI draft began, drawing out the locomotive simile, and remarking on a ravenous pack of Jacksonville teenagers who, crowding the singer, left his pink shirt and white jacket “behind as shredded souvenirs.”

“It’s all happening so fast, there’s so much happening to me,” Elvis told my grandpa. “Some nights I just can’t fall asleep. It scares me, you know. It just scares me.’”

By now we know where Elvis’ train terminated: the King and the porcelain throne, a death with so much bathos it’s hard to make out the tragedy. But while that was the end of Elvis’ story, Papa Fred had another one I’ve only just learned about from Guralnick’s transcript.

Soon after he typed up his story for UPI, Papa Fred went to an RCA party for Elvis at the Hickory House, a jazz venue on 52nd Street. He recalled that hardly anyone came — mostly trade reporters. But Elvis, who months earlier didn’t show at his own signing party, not realizing he was the guest of honor, was there to shake Papa Fred’s hand.

“He said ‘Oh man I was just out in Times Square and bought me a tie,’” Papa Fred told Guralnick. The tie was thin, hand-painted and may have had the Statue of Liberty on it. He bought it for $1. “He was very proud of this thing,” Papa Fred said and, in his memory, wore it with an expensive, lavender-ribboned shirt.

Elvis was impressed by tiny meatball hors d’oeuvres and miniature hotdogs.

“My feeling was that Elvis had never seen a party like that before,” Papa Fred said. “We were kind of looking at it as a kind of low-budget operation. I think he was impressed that they gave him a party of this kind.”

By the end of 1956, the Elvis who could walk around Times Square unmolested or be awed by cocktail weenies was unthinkable. Five months after Papa Fred had his audience with the King, newspapers syndicated his story with the headline “Success Scares Presley.”

Papa Fred had to rewrite his lede, mentioning how he spotted a New York sidewalk scrawled with the chalk warning “Elvis Presley, Go Home” — perhaps prompted by the singer’s appearance on Milton Berle’s show. Papa Fred noted how the album he saw being recorded in January had become a bestseller (it would be the first rock ‘n roll record to top the charts). And while my grandfather was skeptical when Elvis spoke of his desire to star in a film like his idol James Dean, he was obliged to mention how Presley just passed a screen test for Paramount.

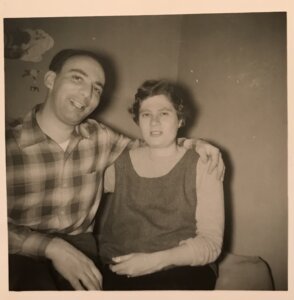

Fred Danzig – who called the Elvis interview his “first exclusive” – continued to write and on Dec. 18, 1956, he welcomed his second child, my mother, the daughter of a man who glimpsed the face of a rock god.