Meet every Jewish name that has ever been inscribed on NHL’s Stanley Cup

Cecil Hart was the first, but there have been dozens and dozens more

Stanley Cup. located between the Clarence Campbell Trophy and the Conn Smythe Trophy. Photo by Getty Images

For Jews of a certain vintage, Passover Seders were synonymous with Stanley Cup chatter, but in 2022, the NHL’s champion will be decided well after Shavuot.

Several Jewish players have contributed to their teams’ playoff prowess this year, most notably the Edmonton Oilers’ Zach Hyman and the New York Rangers’ Adam Fox.

And although neither the Oil nor the Blueshirts made it to the finals, the question remains — just how many Jews have hoisted Lord Stanley, and how many Jewish names are immortalized on hockey’s holy grail, the oldest trophy for professional athletes in North America.

The Cup was donated in 1892 by Lord Stanley of Preston, then Governor General of Canada, and was to be presented to “the championship hockey club of the Dominion of Canada.” Winners from 1893 to 1926 were determined by challenge games and league play, involving teams from across the continent.

At the turn of the last century, Aaron and Bertha Rosenthal were leading members of Ottawa’s young Jewish community. Their son Martin was a board member on the early championship Silver Seven and Senators teams. The Stanley Cup was prominently displayed in the family jewelry store’s Sparks Street window (now the Birks Building in Ottawa). But with the exception of the 1907 and 1915 seasons, only the winning team’s name was recorded on the trophy, not those of individual players.

In the Roaring ’20s, a new tradition emerged, and since 1925, the Stanley Cup is the only professional sports trophy where the name of each member of the winning team is inscribed.

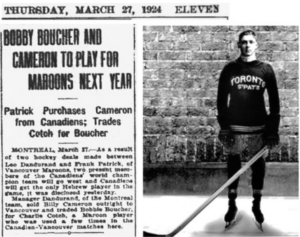

Charles Cotch may have been the first Jew to participate in what were then called the Stanley Cup playdowns. When Cotch was active, Lord Stanley’s prize was still a challenge trophy — involving league champions from the National Hockey League, the Pacific Coast Hockey Association and the Western Hockey League.

From 1922 through 1924 Cotch skated for the PCHA Vancouver Maroons, who lost to the Montreal Canadiens in 1923 and the Ottawa Senators in 1924 in what today would be considered semifinal contests.

Cotch’s affiliation with Judaism is extremely tenuous at best; he is buried in the Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Southfield, Michigan.

The honor of being the first Jewish name on Lord Stanley belongs to Cecil Hart, who served as the Montreal Canadiens’ manager/coach for three cup-winning teams. His name is included on the thin band located on the upper portion of the 1924 trophy, the first won by the Habs in the NHL, and on the silver rings attached to the 1930 and 1931 Stanley Cups.

Hart is credited with signing Howie Morenz, one of the game’s greatest players.

Cecil’s father, Dr. David Hart, donated the Hart Trophy, given annually to the National Hockey League’s most valuable player, in 1924. The redesigned Hart trophy now recognizes the contribution of father and son to the game.

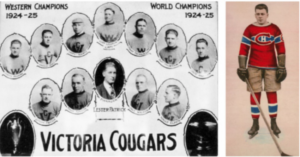

In 1924-25, the Victoria Cougars were victorious; on their roster was winger Wilfred Harold “Gizzy” Hart. Because of his famous hockey surname, many hockey aficionados erroneously concluded that Harold was a member of the tribe, but alas this is not the case.

The first Jewish player to have his name engraved on Lord Stanley was Sammy Rothschild, of Sudbury, Ontario. His team, the Maroons, hosted the first Stanley Cup playoffs at the Montreal Forum. Rothschild later competed for the New York Americans, who recognized his market value as a Jewish player.

In retirement, Sam returned to his hometown and coached the 1932 Memorial Cup-winning Sudbury Wolf Cubs. Before he died in 1987, he was the last surviving member of the 1925-26 Maroons Stanley Cup champions.

That 1925-26 series marked the last year the Cup was a “challenge trophy.” From this point forward, the NHL took full ownership of the Stanley Cup.

Toronto won the Stanley Cup in 1932, their first season in Maple Leaf Gardens, defeating the New York Rangers in three straight games. On their roster was defenseman Alex Levinsky — whose hockey card included the nickname “Mine Boy,” a reference to his father’s enthusiastic cheering.

Levinsky was subsequently dealt to New York and then to Chicago where in 1938, he patrolled the blue line for the Blackhawks’ second Stanley Cup win. Eight American players including the Syracuse born Levinsky skated for the Hawks; this would be the most U.S. talent on a Cup winner for nearly 60 years.

In the 1950s, the Detroit Red Wings became the first NHL team to go undefeated in the postseason, inspiring the appearance of octopi on Olympia ice — the eight tentacles represented the games needed to win Lord Stanley’s trophy.

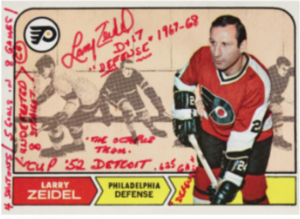

Montreal’s rugged Larry Zeidel was a late season call up for the Red Wings, appearing in 19 regular season and five playoff games with the 1952 Stanley Cup champions. “The Rock” was traded to the Blackhawks in 1953, but after a full season with Chicago, he was banished to the minors. He returned to the NHL with the 1968 Philadelphia Flyers. Zeidel is tied for second for the longest length of time between NHL appearances; he comes in behind Jewish goalie Moe Roberts.

Ed Snider’s contribution to the success of hockey in Philadelphia and the Atlantic region of the United States is immeasurable. It is most fitting that he was the first Jewish owner to have his name inscribed on the 1974 and 1975 Cups. Snider was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1988. He founded the Ed Snider Youth Hockey Foundation, and the Flyers organization continues to do extraordinary community work in his memory.

In 1979, the Montreal Canadiens’ Irving Grundman became the second Jewish general manager to have his name engraved on Hockey’s holy grail. Grundman was the Habs boss from 1978 to 1983.

Morris Belzberg, who opened the first Budget Rent-a-Car franchise in Canada in 1962, had his name inscribed on the cup after the Pittsburgh Penguins won it in 1992; he was the second Jewish team owner thus immortalized.

A veteran of almost 1,300 NHL games with 10 teams, Mathieu Schneider won his only Stanley Cup with the 1992-93 Canadiens. He skated for Team USA at the 1998 and 2006 Winter Olympics and was inducted into the American Hockey Hall of Fame and the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in Israel. He is currently an executive with the National Hockey League Players Association.

Mike Hartman was originally left off the 1994 New York Rangers Stanley Cup list, as he had not played enough games to qualify. However, he was so respected by teammates that they rallied on his behalf. The NHL relented and allowed his name to be inscribed on the last line with teammate Ed Olczyk. After his professional career, Hartman captained Team USA at the 2013 Maccabi Games hockey tournament in Israel. He now hosts a popular podcast on iTunes.

In 1997, the NHL decided to allow a maximum of 52 names on the cup, and has listed criteria for players and non-players. This allows teams to list individuals who they feel made a significant contribution to team success. Consequently, we see longer lists and a few more Jewish names.

Colorado strength and conditioning coach Paul Goldberg has his name on the 2001 cup; Dr. Barry Gerson Fisher, nicknamed “the Mensch” by colleagues and friends, was the New Jersey Devils’ lead team physician for 33 years. His name appears on the 2000 and 2003 trophy

Tampa Bay Lightning owner William M. “Bill” Davidson is the first name engraved on the 2004 Stanley Cup. He is the only owner in sports history to win the NBA title (Detroit Pistons) and the Stanley Cup eight days apart. His Detroit Shock basketball team had already captured the WNBA title in April, marking the first time in sports history that an owner won championships in three different professional leagues within one year.

Davidson was enshrined in the Michigan Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 1986 and the NBA Hall of Fame in 2008. He died in 2009 and was posthumously inducted into the International Jewish Sports of Hall of Fame in 2012.

Under team owners Henry and Susan Samueli, the Anaheim Ducks became the first California team to win the Stanley Cup in 2007. The Jacobs family, who no longer closely identify with their Jewish faith, own the Boston Bruins’ team, which won the cup in 2011. Colby Cohen was called up for the 2011 Stanley Cup playoffs, but never dressed for a game. He is in the team photo and received a ring, but his name is not on the cup

Jeffrey Solomon was part of the front office of the L.A. Kings who won the 2012 and 2014 cups.

Washington Capitals assistant general manager and director of legal affairs Donald Fishman had his name etched on Lord Stanley in 2018. Steve Richmond played 159 games in the NHL from 1983 to 1989, but got his name on the 2018 Cup as the Caps’ director of player development. Washington included goaltending coach Mitch Korn and equipment manager David Marin on their list of names engraved on the 2018 cup.

Jeff Vinik, who purchased a struggling Tampa team in 2010 and personally paid for arena upgrades and invested heavily in the Florida community, has been rewarded with his name on back-to-back Stanley Cups. Jeff Halpern, who missed a game in 2005 to observe Yom Kippur, and whose 14-year NHL career included three seasons with the Bolts, is now an assistant coach with the team. His name is inscribed on the 2020 and 2021 cups as is that of assistant equipment manager Jason Berger.

Tampa Bay has the distinction of having the most Jewish names on the Stanley Cup and may add more in 2022 as they are currently in the finals, hoping for a third straight triumph.

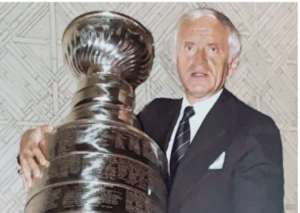

And, of course, no discussion about the Stanley Cup and our lantzmen would be complete without mentioning NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman. He has appeared at every final playoff game since 1993, presenting the trophy to the winning team. For his efforts and genuine commitment to the game, he has been inducted as a member of the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 2016 and the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2018.