A lovin’ tribute to one of the unsung Jewish heroes of rock ‘n’ roll

For a time, Zal Yanovsky was an effective foil for John Sebastian, but it was not to last

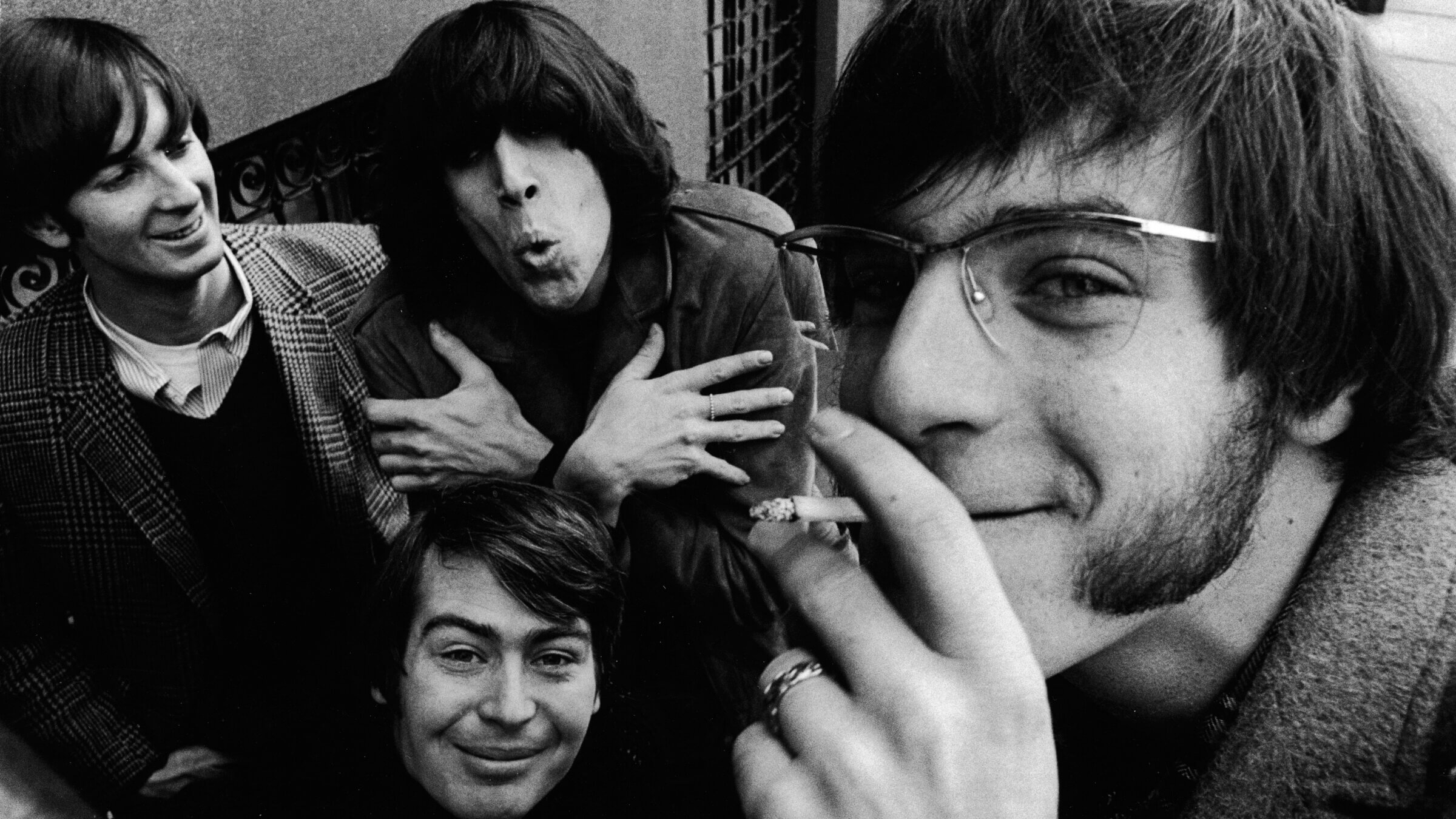

The Lovin’ Spoonful pose on a street in the 1960s. Clockwise from bottom: drummer Joe Butler, bassist Steve Boone, co-founder and lead guitarist Zal Yanovsky and co-founder and singer John Sebastian. Photo by Getty Images

Despite their seven Top 10 hits — including 1966’s chart-topping hot pavement anthem “Summer in the City” — and their (belated) induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, the Lovin’ Spoonful are all too often left out of the “great American bands of the 1960s” conversation.

During their musical and commercial peak, the Greenwich Village-formed quartet were an absolute phenomenon. Their self-described “good time music” — a sunny, electrified, groundbreaking mutation of jug band, folk, country, blues and rock ‘n’ roll idioms — inspired and influenced such contemporary luminaries as The Kinks, Cream and the Grateful Dead.

When the Spoonful arrived in London in April 1966, The Beatles, Brian Jones and Jeff Beck were among the legendary British musicians who greeted them as peers. They appeared in and provided the soundtrack for Woody Allen’s “What’s Up, Tiger Lily?” while also soundtracking Francis Ford Coppola’s “You’re a Big Boy Now,” and they were nearly cast as the leads of the TV show that turned out to be “The Monkees.” But due to fatigue, infighting, artistic differences, business hassles and an unfortunate brush with the law, the band flamed out after a chart run of barely two years.

“The magic’s in the music and the music’s in me,” Spoonful frontman John Sebastian sang on 1965’s “Do You Believe in Magic,” the band’s first hit. But much of the musical magic onstage and in the studio was actually provided by Zalman “Zal” Yanovsky, a Canadian Jew of Russian-Polish extraction who also happened to be the Spoonful’s immensely talented and intensely charismatic lead guitarist.

With his perpetually gurning visage and overgrown Prince Valiant locks, Zal came off like the missing link between Harpo Marx and The Ramones. But beyond his larger-than-life magnetism and penchant for onstage clownery (both of which are still delightfully apparent in clips from “The Ed Sullivan Show” and the 1965 concert film “The Big T.N.T. Show”), Yanovsky was also an incredibly dexterous and creative player. He could fingerpick like a wizened Piedmont bluesman one minute, then make his Guild Thunderbird moan like a pedal steel or sing like a French horn the next.

Unfortunately, Yanovsky’s personality was as mercurial as his playing. His penchant for mayhem would have impressed Keith Moon — he once terrorized some unsuspecting background singers by rolling a fake hand grenade into their recording session — and had a mortifying tendency to act out in crowd situations, like the time he almost ruined the Spoonful’s London after-party by pelting John Lennon with olives.

Following a self-inflicted ejection from the band in the summer of 1967, he recorded one hilariously self-indulgent and deeply uncommercial album (“Alive and Well in Argentina”) before all but vanishing from the music business. Yanovsky’s impulsive rejection of fame and fortune turned him into something of a cult hero, but his unexpected reemergence as a restaurateur and philanthropist in Kingston, Ontario gave his story a much different (and ultimately far more uplifting) trajectory than that of other M.I.A. musical icons like Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett and Sly Stone.

An inveterate shtickmeister, Yanovsky rarely gave straight answers to interview questions in his Spoonful days, and the bitterness he carried with him over his experiences in the music business caused him to prevaricate or clam up entirely whenever he was asked about the band in his later years. Thus, even though he’d become a well-known and deeply beloved figure in Kingston — thanks to his restaurant Chez Piggy, its associated bakery Pan Chancho, and his involvement in various local causes — Yanovsky was still something of an enigma when he died from a heart attack in December 2002 at the age of 57. But nearly 20 years after his death, a biography finally has finally arrived to give us a clearer idea of what Zal Yanovsky was all about.

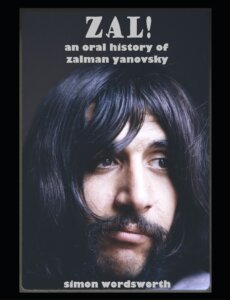

Written by Simon Wordsworth, and featuring a foreword from Yanovsky’s daughter Zoe, “Zal! An Oral History of Zalman Yanovsky” pieces together his wild and whimsical existence from the multicolored shards he left in his wake. Wordsworth, an ardent Lovin’ Spoonful fan who has co-written two previous books on the band, draws upon both archival and recent interviews with many of the people who lived, loved, worked, played and otherwise crossed paths with Yanovsky — in his early life as well as in the music and culinary worlds — along with a veritable feast of photos spanning his life and career.

The picture that emerges from Wordsworth’s painstakingly researched bio is one of an exuberant, complex and occasionally self-destructive man whose irreverent wit and fiercely independent streak rendered him endearing and frustrating in equal measure. Zal (pronounced “Zaul”) inherited both his humor and his unconventional approach to life from his father Avrom Yanovsky, a Russian-born artist who worked as a cartoonist for various ethnic newspapers and leftist magazines, as well as the Communist Party of Canada (of which he was a lifelong member) and the City of Toronto Pest Control Board.

His mother Nechema was a Polish-born schoolteacher who specialized in Yiddish history and language, and during summers she and Avrom would send their only child to Camp Naivelt, a left-wing secular Jewish camp in Brampton, Ontario, where his endless mischief was the constant talk of the counselors. Though he was never observant, Zal’s upbringing nonetheless instilled a sense of Jewish pride and identity that never left him, even at the height of his fame. Not only did he refuse to anglicize his name for showbiz purposes, he also regularly dropped Yiddish words into interviews with teen magazines, which was highly unusual behavior for a 1960s pop star.

Zal’s mother doted on him to a suffocating extent — school friends recall her interrupting his recess time to force-feed him bagels — but her death from cancer when he was 13 deeply traumatized him. Thereafter, he lost interest in school, largely devoting himself to music and petty crime. At 17, his father sent Zal to live with a Zionist uncle and his family at the Degania Bet kibbutz in Israel, an arrangement that only lasted about 10 months. Whether or not the story he often told in his Spoonful days about getting booted for driving a tractor through a wall was actually true, it was clear to all involved that he was far more interested in playing music than devoting his outsized energies to the kibbutz.

Upon his return from Israel, Zal began haunting the coffeehouse scene in Toronto’s Yorkville district. Living primarily by his wits, he busked on streetcorners and often crashed in an all-night laundromat; he met his first wife, actress Jackie Burroughs, when she found him sleeping in one of the dryers. He formed a close bond with singer Denny Doherty, who in 1963 asked Zal to join his folk group The Halifax Three.

From there, the pair formed The Mugwumps, a folk-rock group featuring Cass Elliot. That didn’t last long — Denny and Cass would soon join songwriter John Phillips and his wife Michelle in The Mamas & the Papas — it was through Cass that Zal met a young New York harmonica player and singer-songwriter named John Sebastian. Hitting it off while watching The Beatles’ first appearance on Ed Sullivan together at Cass’s apartment, Zal and John quickly became inseparable friends and jamming buddies, eventually forming The Lovin’ Spoonful with bassist Steve Boone and drummer Joe Butler.

Yanovsky’s high-wattage personality made him the perfect onstage foil for the mild-mannered Sebastian. The latter wrote and sang the majority of the band’s original material, but the former made massive contributions of his own, via both his instrumental abilities and his enthusiasm for pushing the studio boundaries. (That’s Zal whacking a garbage can with a drumstick on “Summer in the City,” and gargling into the microphone for the solo break on their cover of Piano Red’s “Bald Headed Lena.”) And whenever the two men would intricately weave their guitars together, as on “Lovin’ You,” the opening track from their third album, 1966’s “Hums of the Lovin’ Spoonful,” it sounded like a live broadcast from heaven’s front porch.

But dark clouds were gathering even before Hums was recorded. In May 1966, Yanovsky and Boone were busted for possession of marijuana in San Francisco, and the local police — imagining that the musicians could lead them to the “Mr. Big” of the city’s drug scene — threatened to have Yanovsky deported to Canada if he and Boone didn’t cooperate with their investigation. Faced with the immediate demise of their band, and lacking competent legal guidance, the pair agreed to introduce an undercover officer to their circle of San Francisco friends, with predictably disastrous results.

Word soon spread that The Lovin’ Spoonful were “finks,” and though this made no difference to the teenyboppers who continued to scream throughout their concerts, the Spoonful were officially personae non gratae in underground circles from then on. A band with their level of popularity and influence should have been a no-brainer for inclusion in 1967’s landmark Monterey International Pop Festival, but their newfound reputation as narcs made it impossible.

Though the bust has often been cited as the reason for Yanovsky’s departure from the band, Wordsworth makes it clear that his profound dissatisfaction with the Spoonful’s musical direction was the actual issue. Yanovsky thought “Summer in the City” — a song sufficiently evocative and hard-rocking to inspire Eric Clapton to write the music for Cream’s “Tales of Brave Ulysses” — pointed the way forward, but Sebastian was more interested in writing gentle paeans to domestic bliss like “Rain on the Roof” and “Darling Be Home Soon.” Unhappy, but by his own admission making far too much money to quit, Yanovsky increasingly derailed the band’s live performances and generally made his bandmates miserable.

Finally given the boot in June 1967, Yanovsky perversely continued to make his presence known, popping up at Spoonful rehearsals and performances (sometimes as a heckler), and even making a wild-eyed and shirtless appearance at the band’s first photo shoot with his replacement, former Modern Folk Quartet guitarist Jerry Yester. Oddly, there was no ill will between Yanovsky and Yester. In fact, the two briefly became production partners, working together on Zal’s ill-fated solo album as well as recordings by Tim Buckley and (weirdly enough) Pat Boone. “Boone, sing it like you’re singing it out of your asshole,” was one of Zal’s more memorable instructions to the famously conservative singer.

Shortly after his Spoonful exit, Frank Zappa asked Yanovsky to join the Mothers of Invention, but he declined citing his disinterest in playing someone else’s music. But when his Spoonful money started to run out, he signed on as lead guitarist in the touring band of emerging country singer-songwriter Kris Kristofferson.

“He was the only guy I ever had to fire,” Kristofferson later recalled with some amusement, “and he told me that I’d have to fire him one day or he’d tear it all down around us.”

Zal’s fourth show with Kristofferson, at the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival, resulted in a surprise performance with John Sebastian, who was also on the bill. Though their joyous reunion wouldn’t result in any long-term future collaborations, it did allow the two men to begin rebuilding what both clearly viewed as a beautiful and important friendship. By the time of Yanovsky’s death, they’d reconciled to the point where they were visiting each other a couple of times a year.

Yanovsky’s life changed significantly for the better in the early 1970s, when he moved back to Canada and met Rose Richardson, who would become his second wife. Richardson’s calm “earth mother” energy gave Yanovsky the emotional grounding he desperately needed, and he settled in contentedly to life on her farm. In 1979, the couple channeled their shared love of food and travel into the opening of Chez Piggy, a restaurant whose success and international reputation for adventurous high-end cuisine led to the economic revival of downtown Kingston, and further established Yanovsky and Richardson as pillars of the community.

Though by all accounts a talented and inventive chef, Yanovsky’s outgoing personality made him better suited to a “front of the house” position, and for many customers the chance to bask in his Falstaffian glow was as much of a draw as the establishment’s food. When Yanovsky died, the local papers hailed him as the “King of Kingston.”

Yanovsky clearly found peace and happiness as Rose’s husband and Chez Piggy’s co-proprietor, and “Zal! An Oral History of Zalman Yanovsky” — all sales of which benefit the Zal and Rose Yanovsky Breakfast Fund, a charity founded by the couple to provide healthy food for hungry schoolchildren in the Kingston area — does commendable justice to that period of his life, while also digging deeply and colorfully into his formative years and his misadventures in the music business.

The book’s lone major drawback is the way Wordsworth organizes his wealth of material. Each chapter leads off with several pages of Wordsworth’s historical and contextual commentary, then finishes with several pages of quotations in an oral history format, adding chronological detail to the period he’s just covered. The results can be repetitive and, especially in the chapters that span lengthy periods of time, force the reader to flip back and forth between the pages in order to connect the quotations with Wordsworth’s narrative; blending the two elements together would have made for a much smoother reading experience.

Still, little about Yanovsky’s own life was ever smooth, so one could certainly make the argument that Wordsworth’s off-kilter presentation fits his subject well. And ultimately, “Zal!” is filled with so much wonderful information, so many hilarious stories, and so many eye-popping visuals, it’s still an absolute must-read for anyone who was ever a fan of the man or his music, or just wants to learn more about one of the great Jewish heroes of 1960s rock and roll.