Seeking sexual liberty, but staying Hasidic: In a new novel, a young woman tries to have it all

Felicia Berliner’s debut novel features an ultra-Orthodox pornography addict

Haredi men and women walk through a Jewish Orthodox neighborhood in Brooklyn. Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

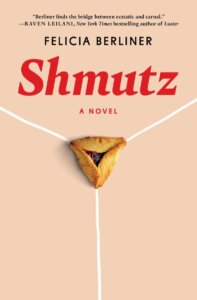

Shmutz: A Novel

By Felicia Berliner

Atria Books, 272 pages, $27

Some books about Hasidic women focus on their desire to be educated, or to not marry the husband that has been chosen for them.

But for Raizl, the protagonist of Felicia Berliner’s debut novel, “Shmutz,” freedom — lofty and impossible — isn’t the point.

All Raizl wants — or thinks she wants — is for someone to “put his tongue down there.”

She doesn’t expect a man in her community to be willing or able to satisfy her this way. Her concern — and her shame — are so stifling that when the reader meets Raizl, she’s in therapy (with a non-Orthodox therapist) and refusing to go on a single date, despite her ripe old age of 18 1/2.

While most women in her community aren’t allowed to go to college or use the internet, Raizl gets a full scholarship to a local college that comes with a laptop. Her dad lets her go only because she studies accounting, a subject that is considered legitimate and acceptable, unlike, say, “biology” or “monkeys.”

Being the devout yeshiva student that she is, Raizl makes a Google search to see what the internet says about God; she ends up in a rabbit hole that leads her to the goyish world of pornography, where people “eat” without “saying a blessing first.”

Berliner published “Shmutz” under a pen name, but she discussed her background at a recent Center for Fiction event. She comes from a non-Hasidic religious community in Los Angeles and has extended family members who are Hasidic. Her goal clearly isn’t to make Raizl some kind of feminist hero. Raizl feels deeply attached to God, and her desire to get married is a constant theme throughout the novel. She has no feminist vocabulary.

But she feels curious about the world outside her own, and that is enough to send her stumbling into it. Little indiscretions pile onto each other — one night she forgets to say the Shema, one day she eats bacon.

Each time she takes another step outside her community, she’s surprised to wake up and learn that God hasn’t struck her down.

Still, while Raizl can’t resist testing the boundaries, she doesn’t wish for total escape. “A freed girl walks into a sea of grief and possibility, and never finds land,” she thinks.

She finds her fears proven valid in the extreme when a college classmate tries to sleep with her on a beach. If not outright rape, the encounter inhabits a gray area consent-wise. At first, Raizl likes how the man’s weight feels on her body, but when he tries to penetrate her, she yells “Nein!” (His response: “Suck it, then.”) Sex turns from something exciting that Raizl can fantasize about in the safety of her Brooklyn bedroom to something that is harmful, demeaning and straight-up unattractive. An instinct, expressing itself in her native language, tells her this isn’t what she wanted.

In fear and trauma, Raizl steps back from her forays into secular life, and she lands a husband. But when she asks her marriage teacher if she has to do things that hurt just because her husband, or chussen, enjoys them, the teacher’s response is less than helpful. “I don’t understand,” she says. “Why would something that pleases your chussen make you unhappy?”

A better question might have been, “Why would you marry someone who you feared might enjoy hurting you?”

Raizl’s journey — in which she is harmed both by the Hasidic and secular worlds — speaks to the challenges women face regardless of where they’re born. In a society that treats women the way ours does, trying to decide whether to stay or leave is, to some extent, a false choice — like trying to pick between the guillotine and heart disease.

Berliner’s novel is insightful in moving beyond binary ideas about freedom and captivity. At times, though, the author — who is not a native Yiddish speaker — is too reliant on Yiddish words for body parts and sex acts to generate the book’s humor. Like kids riffing on a school bus, the novel discomfitingly never asks why the idea of a “schvantz” and a “shmundie” is, apparently, so funny, outside of their pronunciation. The plot can also feel disjointed and slow-moving, like a series of short stories that can’t stand on their own.

Raizl’s grandfather, for example, seemed like he’d become an interesting character; he is the only one in the house with his own bedroom, because everyone is afraid that if they share a room with him, he’ll “tell your dreams back to you in the morning.” But nothing ever comes of Zeidy’s clairvoyance. It’s a cute detail that remains mostly separate from the novel’s plot. The author also hints at interesting things about Raizl’s other family members, but their intriguing character traits fail to move the novel forward or grow into their own plotlines.

Still, the book is full of funny and moving moments, including a heartbreaking scene near the end in which Raizl sits on the floor and hugs her therapist’s legs in a plea for affection. Faced with someone so distraught, from whom so much has been stolen, the therapist is practically forced to break with professional conventions and give her a hug. It’s one of the last meetings the two ever have, as in the world Raizl lives in, marriage means she can’t possibly have any more problems.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture How one Jewish woman fought the Nazis — and helped found a new Italian republic

-

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

-

Fast Forward Betar ‘almost exclusively triggered’ former student’s detention, judge says

-

Fast Forward ‘Honey, he’s had enough of you’: Trump’s Middle East moves increasingly appear to sideline Israel

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.