A friend to artists, an inspiration to students, Alex Rosenberg lived a life of activism and reinvention

The businessman-turned-gallerist has died at 103

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

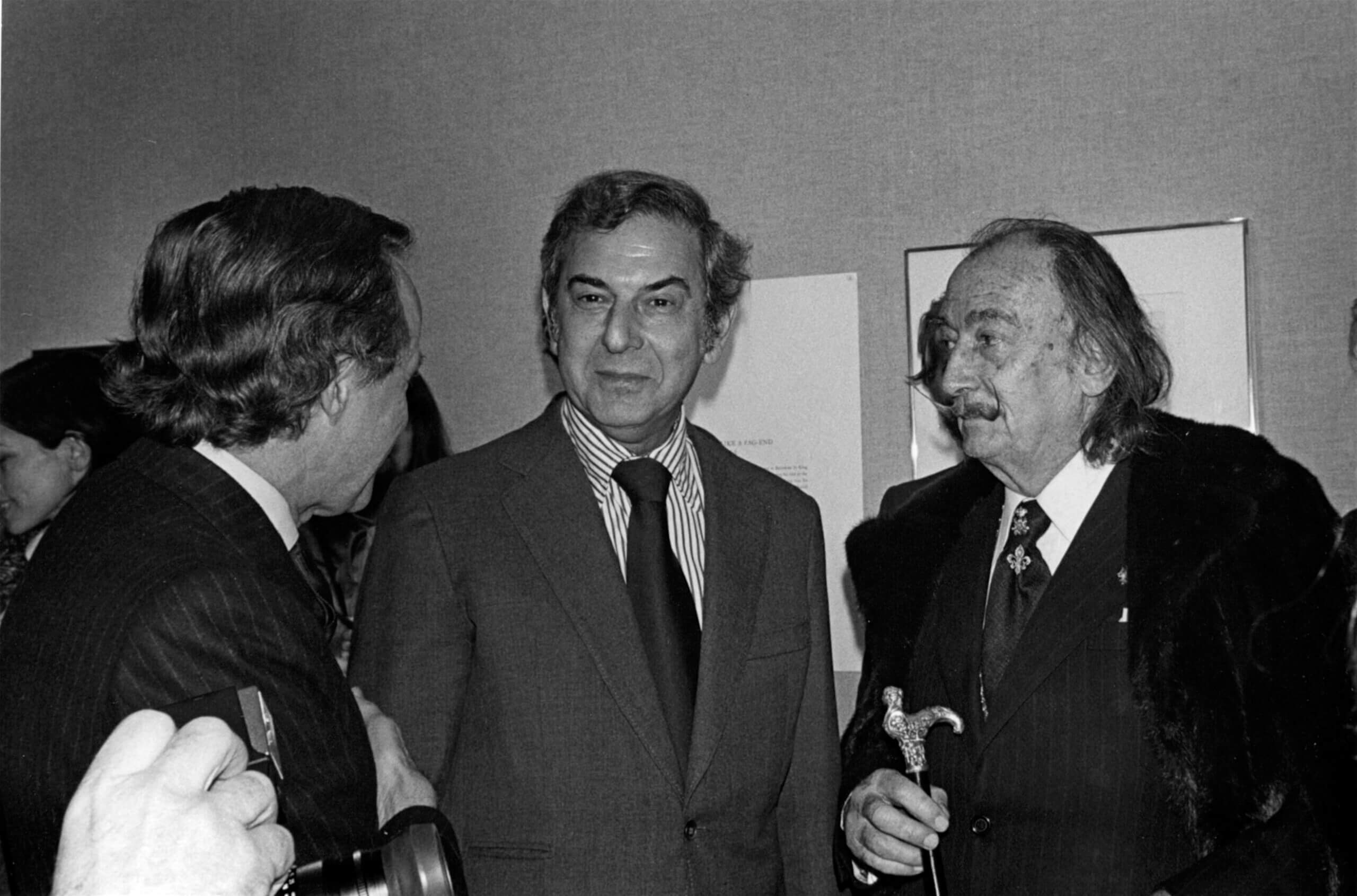

Long after I feared asking someone of his advanced age to give up his time, Alex J. Rosenberg insisted upon returning annually to speak to my undergraduate class on the art market. My students, at Baruch College in the City University of New York, loved hearing Alex, a natural raconteur, tell stories about working with artists like Salvador Dali or Sonia Delaunay. Some still inquire years later about the man who had offered them not only vivid accounts of bygone eras, but also insight into the scandals of the contemporary art market.

Alex recently told an interviewer, “I don’t touch contemporary art because not only does it baffle me, but you can’t come up with any hard evidence. It’s a gamble.” Refusing to retire when he closed his Manhattan art gallery in 1988, Alex reinvented himself as an art appraiser. He fascinated my students as someone who loved his work. The gregarious New Yorker was still working full time when he died of a heart attack in his Manhattan home July 21. He was 103 years old.

Alex’s ventures in the art market began in 1968 when, as a businessman, he got involved financing a portfolio of Salvador Dali’s prints. The project was not going according to plan, so he realized that he needed to intervene to protect his investment. He went to see Dali in Spain to ask him to correct the artwork and then to Paris to supervise the printing. It was the beginning of his friendship with Dali. He eventually became the authority for determining authenticity of Dali’s work; in 2006, he founded the Salvador Dali Research Center to deal with the sale of dubious Dalí works that continue to plague the art market.

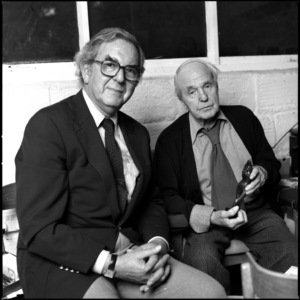

Spurred by his success with Dali, in 1969, Alex began to publish artists’ prints under the name Transworld Art, which he later showed at his own gallery. In addition to Dali, among the many artists he published were Alexander Calder, Mark Tobey, Sonia Delaunay, Matta, George Segal, Romare Bearden, Marisol, Rufino Tamayo, Larry Rivers, Lee Krasner, Alex Katz, Jacob Lawrence and Henry Moore.

I was drawn to the Alex Rosenberg Gallery at 20 W. 57 St., which opened in 1978, since it represented Henry Moore, the sculptor who had been the subject of my master’s thesis. When I first met Alex and his wife, Carole (whom he married in 1977), I was just a young curator busy working at the Whitney on a catalogue raisonné of Edward Hopper. But from about 1990, I got to know the Rosenbergs on Eastern Long Island, where we all spent our summers.

I began to realize that Alex was motivated as much by activism as by art. On behalf of 17 art collectors, galleries, artists, art scholars and the New York-based Center for Cuban Studies, in 1988, he had set in motion a successful lawsuit against the U.S. government by the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee (NECLC) of New York, arguing that First Amendment rights permitted the importation of art from Cuba even though the importation of Cuban merchandise for commerce was otherwise restricted. By 1991, the group won the right for the unrestricted purchase and import of Cuban paintings and drawings. As a result, U.S. galleries and dealers could exhibit the works of Cuban artists and offer them for sale.

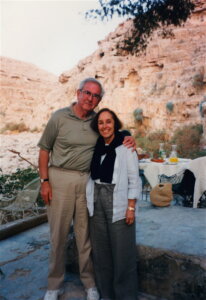

Cuba welcomed Alex’s unsolicited support, invited him to visit, teach, meet Fidel Castro, and awarded him its “Order of Culture” in 1995. Soon, Alex and Carol were encouraging friends to join them on cultural trips to Cuba. They arranged for me to give some lectures at the Ludwig Foundation, which was founded in 1995 by the German art patrons and collectors Peter and Irene Ludwig as an autonomous, non-governmental and non-profit public entity that helps protect, preserve, and promote the work of contemporary Cuban artists in and outside of Cuba.

Learning of Alex’s death, the president of Cuba, Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez, tweeted that “a light of sincere love for #Cuba has gone out in New York, where the collector and professor Alex Rosenberg, to whose generous promotional work Cuban art owes so much, has died at the age of 103.”

This tweet only hints at how for Alex, activism and art were twin passions, often entwined. While he talked to my students about having served as an expert witness in trials for high-value art appraisal cases at first against, and then, as representing the IRS, I gradually came to see that his deepest satisfaction came from political activism and participating in civic activities. I learned that during the Civil Rights movement, he had joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). He then adopted and supported a Freedom School for African Americans in Starkville, Mississippi, to which he traveled with two friends and his adolescent son in 1962.

My students loved watching a 1968 video clip, narrated by NBC newsman John Chancellor, where an elected delegate to the Democratic National Convention from New York — none other than Alex himself — protested when Chicago police attempted to eject him from the floor, claiming that all Eugene McCarthy supporters lacked credentials. Alex recalled being interrogated by the police and guards in the convention hall, but he refused to budge. He continued this concern by serving for many years as vice president of the Center for Constitutional Rights.

Alex’s political awareness began early. He was proud that his mother, Lena Zar Rosenberg, had been a Socialist, “a lover of art and literature, a patron of young writers, a radical and an early agnostic.” He recalled that when he was only 8, his mother became so upset over the 1927 execution of Sacco and Vanzetti for a crime that they didn’t commit that she forced him to “stand online for hours to view their ashes at Stuyvesant Hall on Second Avenue in New York.” He also recounted that his mother made him accompany her to the Metropolitan Museum at age 4 and that he “hated it but somehow it remained with me and colored my life.”

Alex characterized his mother as a “Yiddishist,” who believed in the language, culture and history of the Jewish people. “She was not a Zionist,” he recalled, “but wanted the culture of the Jewish people not to be lost as the Jews were assimilated into the Anglo-Saxon culture that dominated the U.S.A. and swallowed all others in those days.”

Alex’s civic activities extended to Israel, where, among many activities, he served on the International Board of Governors of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, becoming one of three foreign trustees. The many print portfolios he published include sets of prints by Dali and Reuvin Rubin in 1973 to commemorate Israel’s 25th anniversary.

The American Israel Civil Liberties coalition, a group dedicated to seeking justice and equality for Arabs living under Israeli control, briefly had Alex serve as its president in 1987. In New York, Alex never failed to bring contemporary issues to the rituals he enjoyed conducting at annual Passover Seders, many of which I attended.

For many years, Alex asked me to write his obituary. As a biographer, I was flattered, but as a friend, I was too superstitious to do it. Instead, I opened my 2016 article in the Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, “Threading Jewish Identity: The Sara Stern in Sonia Delaunay,” with his vivid recollection of an encounter with Sonia Delaunay, which documented her knowledge of Yiddish:

Sonia Delaunay first met Alex Rosenberg, the New York art dealer and print publisher, in Paris in the late 1960s, when she was in her 80s. Although he could not convince her to make an edition of prints for him, they became friends. Usually they conversed in English, but on one occasion, she turned to Yiddish: “I hear you are going to Israel. Would you please bring me a bottle of Judith Muller’s perfume, Chutzpah?” “Sure,” he replied, “but why are you speaking Yiddish?” “So the maid shouldn’t understand, because if she hears, she’ll want a bottle too.” On his way out, the maid asked Rosenberg to bring a bottle to her too, prompting him to inquire, “How did you know that Sonia asked me that?” “Because I understand Yiddish,” she replied. “Thirty years ago she hired me because I am Jewish, but by now she’s forgotten.”

My publishing Alex’s story seemed to please him. Though I treasured his friendship and his many stories, I had to put aside the materials that he provided for me to write his obituary. Now it is time to commemorate this irreplaceable friend.