How a blind Jewish boy from Baghdad became a great musician

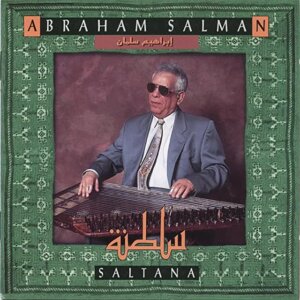

‘King of the Qanun’: From Iraq to Israel, the life and legacy of Avraham Salman

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

One night in Baghdad in 1932, a Jewish toddler looked up at the stars and saw nothing but darkness. He was totally blind.

The odds were that this boy would live a life of poverty and begging.

Instead, he became a renowned musician known as “King of the Qanun.” This is his story, exemplifying the enduring contributions of Iraqi Jewish musicians.

The House of Consoling the Blind

Ibrahim Shahrabani was born in 1930 to a family in Baghdad’s ancient Jewish community. At 5 months old, he contracted an eye infection that blurred his vision. As a toddler, he would look up and see a sky full of clouds when there were none. By age 2, his vision was gone.

He was sent to a school for blind children called Dar Mu’asat Al-’Amiyaan — “The House of Consoling the Blind.” It was founded in 1929 by Eleazer Silas Kadoorie, a wealthy Jewish businessman. Most students were Jewish, but children of all religions attended.

To spare the students from a life of begging, they learned skills like basket-weaving and carpentry. Shahrabani was assigned the vocation of clockmaker, but he only wanted to play music. At the time, the school was the only institution in Baghdad where music was formally taught. Working as a musician was considered a lowly profession, so it was something Jews and other minorities were allowed to do, as ethnomusicologist Esther Warkov describes in her dissertation on Iraqi Jewish musicians.

‘A head full of music’

Shahrabani began to learn qanun, a plucked zither that was popular throughout the Middle East. He eventually memorized thousands of pieces and could perform nearly any genre: traditional suites (called “The Iraqi Maqam”), classical Middle Eastern compositions and Western classical music.

He “has a head full of music,” esteemed Iraqi Maqam singer Salim Shibbeth told Warkov in 1981. “Best in the Middle East.”

Jewish instrumentalists were dominant in Baghdad’s music scene. Every Wednesday, Iraqi state radio’s on-air orchestra would broadcast to eager audiences. One Wednesday, there was silence, and the prime minister demanded to know why. It was a major Jewish holiday, he was told, so none of the musicians showed up.

For the most part, Jews lived peacefully in Baghdad for centuries. Even after a wave of anti-Jewish looting in 1941 during Shavuot in which 180 Jews were killed, Jewish musicians continued to live and work in the city. As a teenager in the 1940s, Shahrabani joined fellow blind musicians in a traveling orchestra called Ikhwaan Al-Fan, or Brothers of Art, founded by Jewish violinist Daoud Akram. Shahrabani remembered those years as “heaven.”

The school for the blind had long advertised its students’ musical services, and Brothers of Art was soon booked on state radio. The group was also in demand for gatherings of women who felt comfortable unveiled in front of the mostly blind musicians, according to Warkov’s research. Money from such gatherings was funneled back into the school’s budget.

Tensions rising

By 1948, the situation in Palestine was boiling over into Baghdad. After Israel declared its independence, Iraq joined an invasion of British Palestine by Arab states. In the Iraqi city of Basra, Shafiq Ades, a prominent Jewish businessman, was accused of aiding Israeli war efforts and was publicly hanged after a show trial.

Tensions spilled over into an orchestra run by Iraqi state radio. Palestinian conductor Ruhi Al-Hamash and Jewish qanunist Abraham Daud Ha-Cohen got into a fight, and Ha-Cohen was fired. Jewish orchestra manager and virtuoso Yusuf Za’arur recommended that 18-year-old Shahrabani replace Ha-Cohen. Popular singers such as Nazem Al-Ghazali then began to hire Shahrabani for their orchestras. He and other Iraqi Jewish musicians prospered despite the tumultuous times and their low social status. “In Baghdad, the musicians lived like kings,” Shahrabani said.

But conditions for Jews were deteriorating. After mass civil service firings of Jews in 1950, Shahrabani and fellow musicians lost their radio orchestra jobs, according to Za’arur’s great-grandson, David Regev Zaarur.

Around this time, Shahrabani was invited to join a state-run orchestra in Jerusalem. The invitation came from Ezra Aharon, an Iraqi Jew who’d moved to Palestine in the 1930s and became a central figure in the creation of new musical genres and ensembles. As the situation in Baghdad worsened, Shahrabani reluctantly agreed to emigrate. He renounced his Iraqi citizenship as required by law, and left Iraq alongside tens of thousands of Baghdadi Jews. He never returned.

A new identity

Shahrabani began using a different last name in Iraq: Salman. Once he immigrated to Israel, he changed his first name, Ibrahim, to the Hebrew name Avraham. He soon became a salaried member of the Israel Broadcasting House’s Kol Yisrael orchestra, playing under Aharon’s direction alongside classmates from the school for the blind. During the 1950s, the orchestra performed 30 to 45 minutes of live music daily, breaking up Arabic-language news or political programming. Salman played any style required: Jewish liturgical songs, Syrian folk songs, songs based on Andalusian Arabic poetry, modern Egyptian hits and the traditional Iraqi Maqam.

Salman also joined the large Iraqi community in the Ramat Gan suburb of Tel Aviv, performing at weddings, b’nai mitzvah and haflat (celebratory parties).

One day, a young Jewish singer named Nahid entered 33 Jaffa St. in Jerusalem to audition for the radio station’s chorus. Salman was among those responsible for the audition. Eventually, the two fell in love, they later told Sara Manasseh, a researcher of Baghdad’s Jewish traditions. Salman wrote songs for Nahid, and they married and started a family.

Salman increasingly became the face of Kol Yisrael thanks to his solos and prominent position in front of the orchestra during its weekly TV broadcasts in the 1970s. So central was his presence that the public frequently mistook him for the orchestra’s conductor, Zuzu Musa, who played in the violin section.

Musicians as state agents

Salman and the orchestra were popular among Israeli Jews from Arab countries. But the station’s main audience was external and its central purpose was propaganda, much like the Voice of America.

A self-described member of Kol Yisrael’s “propaganda team” told Warkov that the station decided to broadcast Iraqi music and “propaganda” in the Iraqi dialect to a contingent of Iraqi soldiers based in Jordan during the 1967 War. The broadcasts were synchronized to the soldiers’ meal breaks. After the war, the station continued to focus externally rather than on Israel’s Arabic-speaking listeners. Singer Umm Kulthum’s music, for example, was broadcast to appeal to Egyptian listeners.

When Egyptian President Anwar Sadat visited Jerusalem in November 1979 following the Camp David Accords, Salman and the orchestra performed at a ceremony marking the historic event.

And in 1980, the orchestra traveled to the border town of Kiryat Shmona to perform for the South Lebanon Army, a client militia of Israel. Hundreds of militiamen attended the concert alongside members of the Israeli military establishment. The event was punctuated by Israeli promises of solidarity with SLA forces, Warkov observed.

Palestinians, however, tended to avoid the station and its music so as not to appear to be cooperating with the Israeli state. The orchestra did include a few Palestinians, but they were “totally isolated from the Arab community and its activities,” Palestinian virtuoso Simon Shaheen told Warkov.

An hour in Ramat Gan

In 1980, at Shaheen’s suggestion, Salman agreed to a rare home session in which they played an infrequently performed classical repertoire with complex improvisations. Each one-upped the other with creativity, playing together as Arab and Jewish musicians rarely did.

Warkov had quietly recorded the session. “How did you enjoy it?” Salman asked. “Tarbani,” she responded, meaning that she experienced tarab, “the ecstasy of listening.” Salman smiled, and with Shaheen still humming, the two left with a reel-to-reel recording of the session preserved for posterity.

His one and only album

Throughout the 1980s, Salman was a regular on the religious music scene, performing at Jewish festivals and private events.

Although he had to supplement his modest orchestra salary to provide for his family, he was still better off than many other musicians. The Kuwaiti Brothers, for example, scraped together a living from a small kitchenware shop in Tel Aviv, while oud player Meir from Salman’s Brothers of Art days ended up working as a telephone operator.

Eventually, Salman grew frustrated by inattentive audiences and an Israeli public that he felt didn’t understand music as Iraqis did. In 1988, he left the orchestra, and in the mid-1990s, he joined the fusion group Bustan Avraham. One day, during a concert with Turkish musician Omar Faruk Tekbilek, Salman began to play brilliantly in an ornate Turkish style. Tekbilek started weeping, and Bustan member Avshalom Farjun knew he had to suggest that Salman record an album. Salman liked the idea.

With music director and co-producer Taiser Elias’ help, Farjun trawled the orchestra’s archives and pulled recordings. Salman supplemented those with newer pieces, including an arrangement of Granados’ “Spanish Dance No. 5.” The effort culminated with the 1997 release of “Saltana,” which brought Salman to an international audience.

The music stops

After Salman had a stroke in 2005, it was difficult for him to speak, but he continued to teach and play religious concerts while gaining new fans. Visitors would hear stories about Baghdad and listen to the enormous tape collection in which Salman precisely memorized the location of each tape.

But his health kept declining. He died of a heart attack in 2014, survived by Nahid and three adult children.

Before his death, Salman lamented that while “people would really cry” when he played qanun in Iraq, modern audiences didn’t appreciate his art. Yet his successful late-in-life album won him new international fans in places as far away as Saudi Arabia, the Salmans gleefully told artist Regine Basha.

Today, Salman’s music survives, both as a testament to the Baghdadi Jewish community, and to the unlikely story of the blind toddler who became the “King of the Qanun.”

The authors offer thanks to Avshalom Farjun, Yair Dallal, Regine Basha, Nili Belkind, David Regev Zaarur, Sara Manasseh, The Babylonian Center for Jewish Heritage, conservation professionals at the Iraqi Jewish Archive, and, for translation assistance, Zahra AlZubaidi.