In the ‘Better Call Saul’ finale, our antihero embodies a Jewish virtue

After 6 seasons, Jimmy McGill emerges as someone we can root for

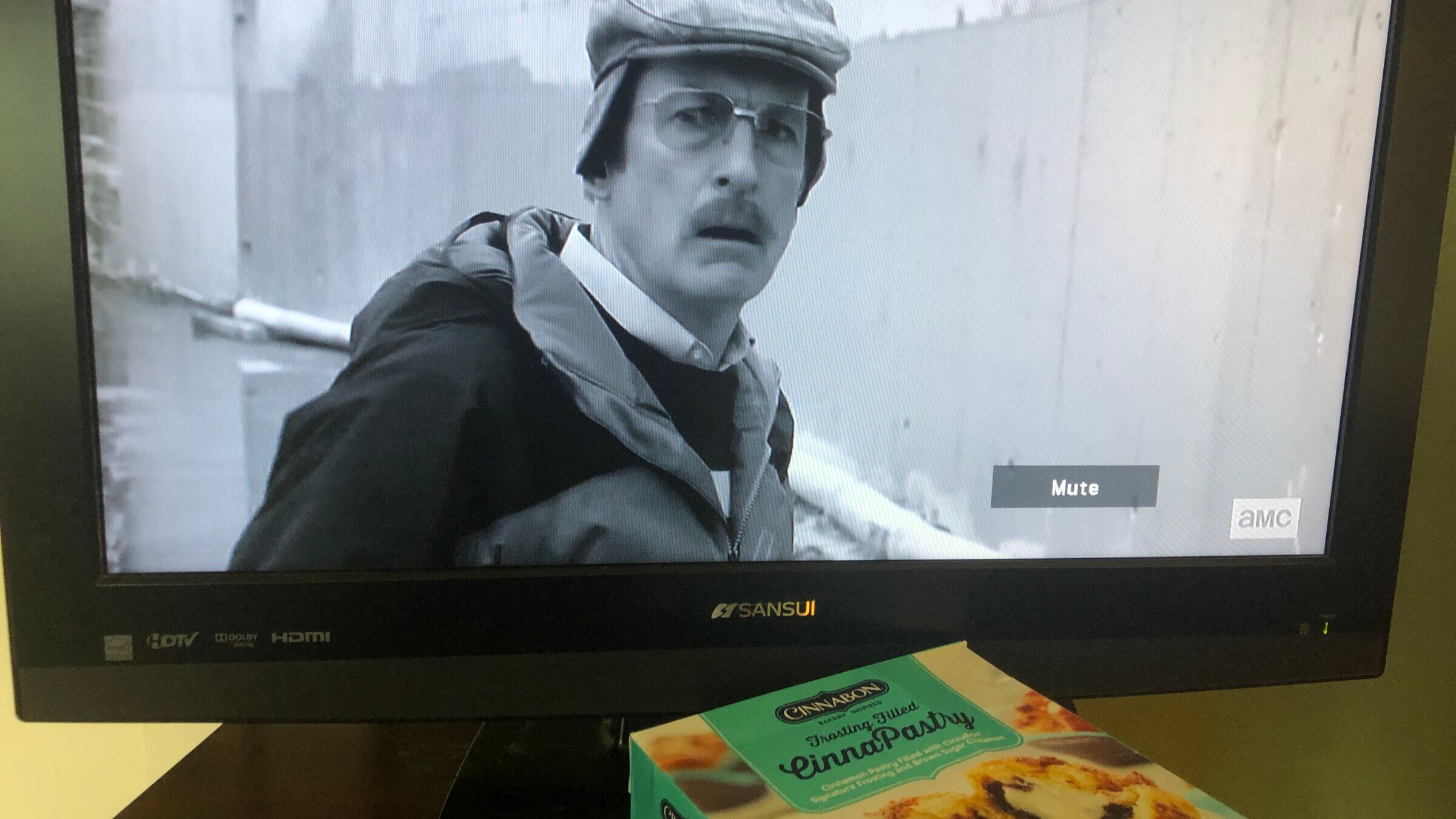

Bob Odenkirk plans his final escape as Gene Takavic, a.k.a. Saul Goodman, a.k.a. Jimmy McGill in the series finale of AMC’s “Better Call Saul,” best watched with Cinnabon pastries, served hot. Photo by Robin Washington

Warning: Spoilers ahead!

Now that “Better Call Saul” has aired its series finale, we can finally answer the question about the title character’s most Jewish attribute:

No, not his stereotypical Jewish-sounding name, concocted from street talk reassurance that “It’s all good, man.” Rather, the Jewish quality might be his altruism – or his conflict over performing acts that benefit himself versus helping others, or both.

As the series makes clear, the Saul Goodman character (Bob Odenkirk) in AMC’s “Breaking Bad” prequel (and ultimately, its sequel, with the timelines of the spinoff both preceding and following the original) isn’t supposed to be Jewish.

It isn’t his real name, either, but a moniker the protagonist first uses as a low-level con artist in his hometown of Cicero, Illinois. Then he’s Jimmy McGill, the ne’er-do-well younger brother of whiz-kid Chuck, who grows up to be a top-notch criminal lawyer at a white-shoe firm in Albuquerque.

Jimmy joins him there, working in the mailroom where quietly, and legitimately, he earns an online law degree – only for Chuck to rebuff him, making it clear there’s no chance he’ll be promoted to associate.

For the finale, I went out and bought frozen-food aisle Cinnabons. My wife enjoyed them immensely as we girded ourselves to learning, once and for all, who this character really was inside.

Yet Jimmy’s street smarts translate well to the law, especially in fighting for the little guy. He heads out on his own, taking in tow, and eventually marrying, Kim, a smart, no-nonsense lawyer, also from humble beginnings who’s just worked her way to associate.

Most of the seasons that follow center around their legal adventures, ultimately involving murderous drug cartels and petty criminals through which Goodman establishes his reputation and makes a killing. In between those plot-lines are his occasional scams, which feed a mischievous fix in the otherwise honest Kim.

Cartels being what they are, it gets serious with a murder Saul and Kim hadn’t expected, and for which their shenanigans are in part responsible. That’s where the prequel ends, scenes from“Breaking Bad” inserted, and the sequel picks up, with Jimmy now re-invented into a third identity: Cinnabon manager Gene Takavic in Omaha, courtesy of a private witness-protection like network.

A traumatized Kim, shedding everything about her life except her name, escapes to a dour life at an irrigation company in Florida, though haunted by her conscience.

Jimmy as “Gene” appears less conflicted about his past and isn’t going to be content making Cinnabons (even with a million or so in cash from his previous life stashed away). Methodically, he reverts to his con-man heists. At first it’s to get leverage over a man who knows him and could put him in legal jeopardy. But then it becomes something else. That’s where the moral issues become most apparent: Is it because he can’t help himself? Original sin? Or boredom?

We’re beginning to wonder what’s motivating him when he gets greedy and pulls a final con that gets him caught. Turns out that since he left for Omaha he’s been the most wanted man in Albuquerque; those cartel murders have him as accessory stamped all over them. Ever the con, he deals, until – spoiler alert – when trading his last bit of info, he accidentally jeopardizes Kim and hands prosecutors the corroboration they need to bring charges against her.

And here’s the moment of altruism: Does he take his own sweet deal, and to hell with Kim? Or recant and undo the damage, sacrificing his freedom in deference to her – and maybe even love?

Throughout the entire series, we’ve wanted to like this guy, or I have, even when his brief sparks of caring for the little guy were horribly offset by let-the-chips-fall-where-they-may violence for the love of the game. In fact, I celebrated his character, or the last one, anyway: For the finale, I went out and bought frozen-food aisle Cinnabons. My wife enjoyed them immensely as we girded ourselves to learning, once and for all, who this character really was inside.

Saul Goodman may have ultimately become the embodiment of Hillel’s axiom on altruism: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?” Throughout the series, he’s had no problem being for himself. But doing so at the cost of harm to Kim may actually have forced him to ask if it was worth it, and if he could live with himself.

I’ll go with that, and it’s not quite a spoiler because the last few minutes were sufficiently confusing. We had to watch it a second time and still were baffled without a copy of the Code of Criminal Procedure handy.

But in the end, I think he lived up to his name.