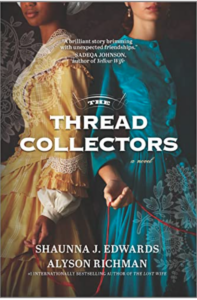

An Ashkenazi Jew, a New Orleans native living in Harlem — and the beginning of a beautiful collaboration

Alyson Richman and Shaunna J. Edwards have joined forces to create ‘The Thread Collectors’

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

If you’d walked through Bryant Park in midtown Manhattan on a warm Friday in June 2020, you might’ve observed two women sitting there for hours, talking and talking. At first glance, just two friends meeting in the only way that felt safe — outdoors, masks cautiously lowered — as the first wave of COVID cases retreated and gave New York City a bit of a reprieve. But if you’d caught snippets of their conversation, you’d know they weren’t just catching up.

It was Juneteenth, and for weeks, Americans all over the country had been protesting police brutality and racism after the murder of George Floyd. At least two marches had begun right in Bryant Park and another had ended there at the main branch of the New York Public Library after protesters sat and knelt in the street as part of a nonviolent demonstration.

Now, these two women — one, an Ashkenazi Jewish woman from Long Island; the other, a Black New Orleans native living in Harlem — were mapping out the plot of a Civil War–era novel they’d decided to write together in the wake of recent events. Each was drawing on her own family history.

Alyson Richman and Shaunna J. Edwards had been friends for a decade by then. Richman is a writer with seven other novels under her belt, including “The Secret of Clouds” and “The Lost Wife.” And Edwards is a lawyer turned diversity, equity and inclusion leader. They met at a party for lawyers that Richman attended with her husband.

Their novel, “The Thread Collectors,” follows a Jewish couple from New York City and a Black couple from New Orleans as their stories converge. Jacob Kling enlists as a musician in the Union Army, leaving behind his wife Lily, who describes herself as “an abolitionist, a suffragette, and a Jewess.” Down South, Jacob meets William, a musical prodigy who’s escaped slavery to join the fight for his freedom. He, too, has left his beloved behind, but unlike Jacob, he can’t exchange letters with Stella — not only because he can’t read or write, but also because he can’t risk being found and captured. Meanwhile Stella — who was forced into sexual bondage at the hands of William’s master — uses bits of Confederate intel she gathers from a loose-lipped Master Frye to embroider maps that help other men escape and join the Union effort.

That Friday in the park, Richman and Edwards imagined the entire arc of the novel. By the time they parted ways, “we had an idea of what we wanted,” Richman said, of “where we began and where we wanted to end.”

Based on a true story

Richman has long wanted to write a Civil War novel inspired by the stories she heard from her grandmother: After immigrating to the U.S. from Germany in the mid-19th century, one great-great-great uncle, Jacob Kling, stayed in New York, while his two brothers, Abraham and Monroe, settled in Satartia, Mississippi, to expand the family mercantile business. When the Civil War broke out, Jacob enlisted as a musician in the 31st New York Infantry Regiment, while Abraham joined the 29th Regiment of Mississippi, Richman explained on a Zoom together with Edwards earlier this month. “We have records that he ranked in as a sergeant but ranked out as a private, so he was a very bad Confederate soldier. But still, he fought on the Confederate side.”

“I’ve always been fascinated by this family lore about having two great-great-great uncles who fought on opposite sides, and how their different positions on slavery had permanently divided the family,” Richman said. Beyond family history, she was struck by efforts after the war to find and retrieve the bodies of hastily buried soldiers. “I had this sort of loose idea that it would be very interesting to have a novel in which a white woman from the North goes down South to find her husband, believing he’s dead, and that there was a map created somewhere by a Black soldier of where he might be buried.”

Richman shared these musings with Edwards, who studied literature as an undergrad at Harvard. They’ve always bonded over books, and Richman regularly turned to Edwards as a sounding board for new ideas.

Edwards immediately suggested that the map Richman imagined be recreated using repurposed cloth and thread. Black Americans have turned to food, music, and textiles — like the quilt Edwards keeps made from pieces of her great grandmother’s field dress and her grandmother’s house dress — as a way to preserve history. “We didn’t have written histories,” she said. “When your forms of communication are limited in that way, it really starts to force you to look at the other forms of communication and how you pass things on.”

Growing up in New Orleans, Civil War history felt ubiquitous for Edwards. “If I had had more self-confidence in college, I would have been a history major,” she said. “I basically thought that history was the province of white jocks, and I didn’t really think of what I now understand history to be, which is just a collection of stories.” So when Richman started talking about it, “I was intrigued. But I spitball ideas for a living,” Edwards said. “We would chat about it sometimes. But I never conceived of it as being something that we could do together.”

The right moment

Three years later, when rage over American racism and violence boiled over in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, Richman thought again about this long-simmering idea. She’d never forgotten that first conversation with Edwards. There was “this palpable energy between us, this immediate exchange where I was learning something,” Richman said. “And I thought, I really would love to write this book with Shaunna.”

Edwards’ first instinct was to say no. “It was probably one of the lowest points in my career,” she said. “After the murder of George Floyd, being the head of DE&I in a large, global organization, but also being a Black woman — you’re doing all of this emotional labor, you’re trying to figure out where to put all of these emotions, and at the same time, you still have to be strategic and carry the load and be a spokesperson. And I was really struggling.” In the midst of all that, Edwards said, “I didn’t think that I could sit in something else that was painful.”

Edwards’ then-fiancé, now-husband encouraged her to think about it differently — “as a place to put those emotions,” she recalled, and as a way to “move through what was a very painful period of time and try to make something beautiful out of it.” So she told Richman she’d be willing to try.

There was a lot on Edwards’ mind going into their first multi-hour brainstorming session in Bryant Park. She was wary, for instance, of falling into the trope of the “magical Negro,” in which a Black man shows up to move the plot forward, but “really, it’s still centered around the white experience,” Edwards said. It was crucial to her that “the book be equally balanced.”

Within about half an hour of sitting down, Edwards said, they had an exchange that “was like the cornerstone of our pact on how we would write this book.”

“We were talking about racism and I said, ‘Well, in my family, I was always taught to be colorblind,’” Richman recalled. “And I meant that in the most sincere, earnest way. And Shaunna right away said, ‘We cannot write this book if you don’t see my color.’”

At one point during our Zoom call, Edwards stepped away from the screen and came back with two framed photographs — she held up one of her mom’s parents and then the other of her dad’s parents, two Black couples with a stark disparity in skin tones.

“Color has always been something that I’ve lived with and something that my family — we don’t talk about it much, but it has impacted how we have seen the world,” said Edwards.

As Edwards and Richman worked, they continued to broach sensitive subjects and learn from one another. In stories of slavery, Richman discovered compelling echoes of Holocaust testimonies she’s much more familiar with. And she learned, for example, about Louisiana’s Code Noir, the subject of one of Edwards’ law school papers. Edwards, meanwhile, learned about General Grant’s expulsion of Jews and the origin of “Shoddy,” an antisemitic slur a fellow soldier tosses at Jacob one night.

Together, the authors shaped characters who also share history, culture and customs. In one scene, Jacob and William must bury a friend. First, William lays the body down facing east, according to Gullah traditions, and marks the grave with one of the deceased’s most prized possessions. Then Jacob says the mourner’s Kaddish. In that moment of shared loss, two men who’ve already bonded over music, Edwards said, “are finding a different level of friendship.”

Friends and writing partners

After Juneteenth in the park, Richman and Edwards collaborated mostly remotely using shared Google docs — falling into a rhythm that made Richman feel like they were “one working brain.” She’d never worked with a writing partner like this. “It could have turned out really poorly,” Richman said. “It could have become really combative and difficult. But I actually feel closer to Shaunna than I ever have before.”

Edwards felt similarly: “It was labor intensive. But it wasn’t difficult, if that makes sense,” she said. The project established a level of trust that allowed her to “have more honest conversations about my experience as a Black woman than I’ve ever had with a friend who is not Black,” she said. It “has changed me and my ability and my willingness to be honest in friendships, and really how I think that we can make progress in the world.”

The experience of writing “The Thread Collectors” has deepened the writers’ friendship as well as their love of history and their shared belief in the power of stories to foster empathy and spur change. They’re already dreaming about turning the book into a series. The next installment, they hope, could follow Jacob and William and Lily and Stella as their lives continue to unfold in the aftermath of the war. “I already have Reconstruction books by the couch,” Edwards said.