I was a secular English teacher in an Orthodox school

Teaching Arthur Miller and Sherman Alexie to a group of yeshiva bokherim made for more than a few challenges

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Editor’s note: This is a republication of Larry N. Mayer’s 2013 essay, which was a finalist for a Deadline Club award. In light of The New York Times’ recent investigation into education at Orthodox schools, we are revisiting the piece.

Though he led his own Orthodox congregation several blocks away, Rabbi Berman was in charge of the yeshiva’s secular education program. A youngish man with an expressive face and a brown beard, he seemed to be moonlighting as principal — a way to earn extra money and perhaps satisfy a lesser passion for teaching. He smiled easily and was shy in a scholarly way. Upon meeting at our interview, he turned away from me, pumped his fist like a little boy, and whispered to himself, “Yes! Yes!”

I could see him smiling. I was Jewish, I had 20 years of experience teaching English in high schools and at the college level, and I had even written and published a book on Jewish identity in Poland, which I’d brought to our meeting and placed on his desk. Only now does it occur to me that he never looked at it. During my tenure at the school, he would be a good boss in that he rarely interfered. Yet he gave me fair warning: Regular high school subjects for these Haredim (ultra-Orthodox Jews), he said, “didn’t count” in the bigger scheme of things. Non-religious subjects were a time to unwind, sleep or break down the walls of the old Victorian house. The yeshiva bokherim, as they are called, studied Talmud and Torah all day, getting up at 7 a.m. and not finishing till 9 p.m. The hours from 3 p.m. to 6 p.m., when they studied literature, history, science and math, were considered down time.

These kids were going to be a handful, yet I imagined I could handle anything. Because of my wife’s academic career, we had relocated several times as a family and I was used to taking unusual teaching jobs. I started as a high school English teacher in the crack-infested South Bronx of the early 1990s, moved my way around the country to a school in a juvenile detention home in Ohio, to several at-risk high schools in inner city Boston, and finally to teaching Holocaust studies and creative writing to mostly apathetic college students in the Pacific Northwest. I was up for this latest challenge. How hard could it be?

On my first day, I walked uncertainly up the steps of the front doorway. In the small vestibule, deep-brimmed round black hats were resting on shelves and brown-covered prayer books were piled carelessly. A sickly-sweet smell pervaded the building. I peeked into a central room; several boys were praying, others studying. I had asked Rabbi Berman if I needed to wear a hat or a yarmulke out of respect, and he’d told me to wear what was comfortable, so I wore a nice button down shirt and my best suit pants.

I was ambivalent. On the one hand I felt reassured by the familiar Jewishness of the setting, but on the other I felt a sense of alienation, distrust and unease. Though I strongly identified as Jewish, I was hardly religious, and I had formed my own opinions about the crazy Haredim in Israel — for instance, those who were making world headlines by forbidding women to sit in the front of buses, and spitting on young girls in short-sleeved blouses.

I quickly got a feel for the three-story building. There were no paper towels in the bathroom; the toilet seat jiggled. A leaning mattress blocked the hallway to the semi-kitchen.

“A class in session,” the rabbi told me. “We use every part of the building.” My ninth grade class was to meet in the basement cafeteria. We would work among the rodent traps and their unmistakable blue pellets of poison. The room smelled of institutionalized food, large pots of barley soup and cleaning products. I immediately wondered whether or not these teenage boys wanted to be here at all. The black hats and pants. The white shirts. The lack of girls. The shabby facilities.

The main office looked like a converted storage closet, where the other rabbi, who was the head of the Yeshiva — Rabbi Alter — maintained his desk of clutter. A photocopy machine from around the age of the bicentennial sat crookedly on a pile of papers. The first thing I said to him was, “I thought you’d be older.” He resembled a Grateful Deadhead in a suit; he nodded and murmured, smiling. He looked to be hiding in his little hovel, slouching low in his chair, with a phone crooked against his shoulder, and Chinese food leftovers skulking among the ruins on his desktop. In the same room, the “secular” rabbi — Rabbi Berman — handed me his black binders of old lesson plans, covered in what looked like flakes of dandruff and dried yogurt.

“No Shakespeare,” Rabbi B told me. “Too much talk about love. The only love they need to know about is in the Torah.” To his credit, I did get the impression that he was rolling his eyes at that idea.

“What about poetry?” I asked. “Can we read poems?”

“You can try, but poetry is either love or death. And last year the students complained that all the poems they read were about death.” So death, as I understood it, was played out. And the other option — the love option — was out. And we couldn’t read novels because students were not supposed to have work outside the classroom. The real day was for learning Torah.

“You can also do grammar with them,” he said. “It’s good to do grammar.”

I had four Moishes in my first class of 10th-graders, but no one would tell me his correct name until Rabbi B came in. The senior class had three Yehudas. And the freshmen had two Shlomos — the good one, and the bad one. In the end, I found it easier to call them by their last names, even though it felt old-fashioned and a bit disrespectful: “Sit down, Foxman. Take a seat, open your notebook.”

Before class I had seen several of them outside playing basketball at a neglected looking hoop. The court was overgrown with weeds and scattered trash, yet they played with all the fervor of normal teenage boys, though it looked harder to run and jump in their formal outfits.

In front of me, I saw a palette of white shirts and pale, pimply faces. A few had payot, or side locks, like little old men without the beards. One boy told me that from a religious standpoint only sideburns were required, but he kept his hanging curls for what I rephrase here as “extra credit” from God. Was I Jewish, they all wanted to know? More importantly, “Is your mother Jewish? Is your wife? If not, you must be stupid.” I sang what I could remember of the haftarah from my bar mitzvah, and they were pleased. They argued over which parsha — the weekly Torah portion — it was from. It was almost cute. And in some sad way I felt as if I belonged.

Rabbi B had wanted to be sure I could pronounce the guttural “ch” sound, instead of the American “k” sound. So before class he’d prepped me. I did it properly — gave it that extra phlegm in the throat sound — which pleased him also. It’s very important to pronounce their names correctly, he told me. They get a big kick out of your making a mistake — easy to do because of the constant confusion of whether their names were Hebrew or Yiddish, or some form of Judaicized English. For example, was it Levi like a levee in the Mississippi River, or Levi, like a pair of jeans? Or Levi, which rhymes with “Navy”? When I came to the name Reicher, I made sure to gutturalize the “ch” but of course they all laughed because in this case it was pronounced “Riker,” like the prison island. In the end, though, what mattered most was that my mother was Jewish.

•

The first story I assigned was “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson, about an entire town stoning one of its own to death. The boys didn’t see any parallels between themselves and the characters in this horror story who are also bound by rituals and traditions.

“Crazy story,” they said. “Why are you making us read this?” I told them the author’s husband was Jewish. It’s true. I was reaching for a connection. I also wondered why the rabbi himself had given me this story to teach in the first place.

It was amazing how united they were. How they worked together like a pack.

“Yes, you have to break them up, figure out who the leaders are,” Rabbi B told me. Because there were four Moishes in one class, I started to call all 12 of them Moishe and worried that this might be construed as antisemitic. My father’s name is Moishe, I told them. It’s also true. They liked that.

After two days, part of me began to wonder if this wasn’t a school for kids with behavioral problems. One student, whose name sounded like “Sirloin,” prayed the entire time I tried to talk. I checked out the school’s rating online. One angry teacher had posted anonymously on the site, and said, among other things, that the school was “sadly lacking in resource [with] no clear behavioral policy in place.”

But what were they doing that most high school boys didn’t do? Were they really any worse? Well, for one thing, many had a smugness about them, and gave the impression that I must have been a loser for teaching at their school. Later, I would encounter the word kefira, a derogatory term for any person or thing believed to be in denial of God, sort of like treyf, or non-kosher. Was I kefira? Had I told them too much when I confessed my wife wasn’t Jewish? What was I trying to accomplish? Despite their exclusionary pride, it was nice having them ask me so many questions, as if they were genuinely interested and concerned for my well-being. As a Jewish soul who had lost his way, I think to them I was hardcore kefira.

The ninth-graders were a little better. They were new to the school, unsure of what to expect and what was expected. We read a short story by Langston Hughes, “Thank You, Ma’am,” about a young teenage boy who learns a lesson about trust and respect when he fails in his attempt to steal a woman’s purse. I asked them to take turns reading out loud. The story’s characters speak in dialect — the African-American vernacular of the 1950s. One boy read it with a thick, bassy, Southern-inflected drawl. I told him he was bordering on racism. He responded that he was from Baltimore and that’s the way “they” talk. I should stop being so sensitive, he said, because in his city “they” were the ones who “do all the stealing.”

“Realism, Mr. Mayer, not racism.” What could I say? Political correctness, I soon detected, was also clearly kefira.

•

After a few days I thought things had gotten better, or perhaps I’d become used to them. At the end of the day, I talked to the frustrated history teacher who said he worked here only because he’d been laid off and was looking for a full-time job. He was not Jewish and therefore seemed to feel much more detached about the job. He planned on leaving, and when he did, they could all go to hell.

But I’d actually gotten a little excited about teaching the 12th-graders. Yes, all seniors in high school are a bit “checked out,” but at least they tended to be more mature. Something physical happens to most students between 10th and 11th grade, and so by the time they are seniors, their brains are ready to reach a formative stage of adulthood.

We read a personal essay by the Native American writer, Sherman Alexie. It was called “Superman and Me,” and it was about how he learned to read from comic books; more importantly, it was about how the world expected him, as a Spokane Indian, to fail, and how he would go on to counter that expectation and succeed. The seniors hated it. They counted how many times Alexie used the word “I” in the story.

“He’s arrogant,” they said. “He’s self-centered. He only says, ‘I, I, I.’” I wasn’t sure if they were just trying to disrupt my lesson or if they were truly offended by Alexie’s brazen writing style. I asked them to summarize the story for me. That’s all — a basic writing skill. Write a summary. No opinions, I told them, just what he said.

“First be objective,” I told them. “Then you can respond with a more subjective approach.” They were not stupid, but they didn’t know what either of those words meant.

After class, I wondered if their objection to Alexie’s overuse of the word “I” could be construed as a reflection of something positive about the values of Jewish culture. Perhaps they were just bound by what was best for the group and not the individual. I vowed to judge less harshly.

•

I heard a loud crash before I entered the street-level room. The venetian blinds were on the floor; someone had smashed the broken panel out of the floor level window.

“The window has been broken all year,” one of the boys claimed. “It just got more broken when we opened it.” I called Rabbi B and told him I wasn’t sure what had happened, but it was clear to me that the boys took great pleasure in the fact that the pane now had a gash in it, and that there were shards of glass on the floor in the back of the room. Rabbi B was angry, but they were clearly not afraid of him. They mimicked his speech when he walked out. After all, he was not the “real rabbi.” The real one whom they feared, Rabbi A, did not concern himself with the mundane details of secular studies, and was only called from his office when all hell broke loose. So far, I’d never seen him except when I went to his office to make photocopies, one at a time.

During these visits to the inner sanctum, I learned how insignificant secular studies were. The antiquated photocopy machine ran out of toner the first week I was there and it took weeks to replace it. The rabbi waved my concerns away. A friend of mine experienced in working with the Haredi community explained that the schools themselves were not truly committed to secular studies, and offered non-religious classes only as a means to secure funding from the state.

Back in the 10th grade classroom, I broached “The Lottery” again, prompting little constructive discussion, and lots of random shouting. I took some of the blame for this. After all, in an attempt to be casual, I didn’t insist that they raise their hands.

“We killed our English teachers last year, several of them,” one student joked. “We buried one in the basement dining hall. You can see that huge lump below the floorboards.” One moon-faced kid with braces and a Russian accent said, “I will shoot you, mister.”

“Emotionally,” I countered. “I’m afraid you will kill me: emotionally.”

The ninth-graders in the meantime were beginning to come out of their shells. The two Shlomos, who had been “the good one” and “the bad one,” were now both the bad ones: the evil Shlomo brothers. One student complained to me that one of the Shlomos wouldn’t let him sit next to him in the back row.

“So sit somewhere else,” I told him. I turned around to write something on the whiteboard. I heard a screeching desk and felt the vibrating floorboards, and turned around to see Shlomo (yesterday’s “good one”) holding Shlomo (“the bad one”) by the shoulders, trying to shake him to the ground. I broke their clinch and walked them upstairs to Rabbi B. Later, he came down with both boys and said in a practiced, teacherly tone that he had never witnessed violent behavior in the school before.

“We use words,” he reminded them.

•

On the Wednesday of the third week, I called Rabbi B to tell him I wasn’t coming in, and for that matter, I didn’t want to come back: I quit. I’d never had a group this bad, not in the South Bronx, not in the Ohio detention home.

“We’ll work on this together,” he told me. “You need to pick out the leaders, and then things will calm down.” But I couldn’t come back. I told him that these were the wildest and most unpleasant kids I’d ever met. Recalcitrant, obnoxious teenagers are cliché. But these guys were unique. Maybe it was their lack of respect, which seemed to come with a broader blessing or sanction. You knew they didn’t act this way with Rabbi A.

“But we are counting on you. We hired you. We ignored other people because we thought you’d be a great teacher,” Rabbi B said.

“OK,” I said. “I’ll come back tomorrow, but today I can’t make it. If you let me stay home today, I’ll give it another chance.”

Thursday morning when I returned, the students actually seemed less threatening, and more friendly. Maybe they’d missed me? On the Tuesday before my truancy, they had been making fun of me because my shirt was inside out. Because I had dallied for so long before leaving for school on Tuesday, I had left the house with my shirt inside out and hadn’t noticed.

News got around the school pretty fast. Kids were fingering my collar to get a better look. Even the 11th-graders — the only group I didn’t teach — were recruited to come and see. In a mood of retaliation, I told one of the kids to look at his own shmattes before examining me. Dirty rags? He looked shocked. Was I calling his tsitsis shmattes? Fearing that I might have insulted his religious garments, and might lose my job in a shameful manner, I quickly said, “You wear the same white shirt and black pants everyday, and you laugh at me.”

But the pack mentality of the attack stayed with me. And perhaps also it was the chutzpah of their disrespect. They knew me barely three weeks. And yet there they were, surrounding me, checking the label of my shirt, and teasing me without any regard for my humanity. Where was the compassion?

At the start of the next week, we were getting ready to read “Dusk,” a story by Saki. It’s a tale about a con artist who gets money from someone in a park by pretending to have lost a bar of soap. The story is filled with subtle ironies and many references to dusk and blindness. If this group wanted to learn, there would have been plenty to extract from it. They took turns reading aloud — a boy named Avraham decided to read it with an Italian accent. Please, I implored them, let’s read the story aloud, seriously.

“But we read it already,” they said. “It’s about a guy who gets money from another guy after he finds a bar of soap. There’s nothing else to say.”

I silently countered them by handing out a sheet with some questions about the story, to which they needed to write the answers. One of the four Moishes said, “Why do we have to write the answers just because you can’t control us?”

The commotion level was up again. Whom would I report to Rabbi B today? Sirloin was praying as usual. Another student was studying Torah. One of the Moishes — the smart one — had his chemistry textbook open and was balancing equations. Still another was going in and out of the room so many times that I asked him if he had a bladder problem. And each time he repeated, “I’m very smart, Mr. Mayer, I just don’t work to my fullest potential.” Foxman as always was in the center seat in the back, with a big grin on his pimply face. It was hard to catch him doing anything specific — other than giggling, screaming, mocking me or fiddling with the cords on the blinds. This time he had it around his neck as if he were going to hang himself. It was a thought.

•

By my fourth week, nothing had gotten any better. The ninth-graders down in the basement were wilder than ever, and the late September temperature was hotter. For some reason, the cellar fan didn’t work, and the kids continued to whine about the unbearable heat. But I was afraid to open the rear door because I’d discovered that the backyard of the school, lined with trash cans, was a haven for rats. After class, during one five-minute break, I witnessed the 11th-graders, for sport, stoning one of these rats to death. And though I felt sorry for the poor little thing, I was disappointed that it wasn’t my monstrous 10th-graders doing the killing. Had that been the case, I could have referred them back to the stoning in “The Lottery,” and made some kind of analogy.

Tiring of the beat-up old literature textbook we were using, I asked Rabbi B if I could teach Elie Wiesel’s “Night.” It appeared to be the perfect solution — it told the story of a 14-year-old Orthodox Jewish boy, whose faith is challenged while surviving Auschwitz. Rabbi B was quick to reject the idea. “There are some pretty obvious reasons why it isn’t a good book to do,” he said. Of course, I should have known — Wiesel questions his faith. Although I didn’t think Rabbi B considered the book itself bad, he did think it would be unacceptable for this specific group. Literature wasn’t supposed to touch them too closely or prompt questions no one wanted asked — or answered. All truths were ultimately in the Torah, and anything that threatened this concept seemed to be forbidden.

Around Halloween, we had gotten used to each other, more or less. I’d come to understand that keeping the classes in order was not really my job. The science teacher screamed at them. Fed up with their racism, the history teacher walked out of class once and didn’t return till the next day. The rabbis didn’t seem to care as long as no one was killing anyone else. So rather than encourage discussions, which became unruly and chaotic, we would read aloud. (Accents be damned!) Then I would assign them written questions, and a final essay in each unit. In some pedagogically compromised way, it worked. They were very good at doing rote work. They liked questions with clear answers in the text.

When things got boring, I pulled out an old trick, which was to talk like Donald Duck. It put them in a kind of childlike trance, as they would repeat over and over, “Again, Mr. Mayer. Do Donald Duck again.” I spent part of one class teaching them the fine art of Donald Duck talk, which comes from vibrating the back lower gums of the mouth against the inside of the cheek.

“Remember, there’s no throat involved,” I reminded them. “It’s all in the cheek.”

Other times I would burst into children’s playground handclap songs that my fourth grade daughters had taught me the night before: “Happy llama, sad llama, mentally disturbed llama, super llama, drama llama, big fat mama llama, crazy llama, don’t forget barack o’llama.” They called me crazy, they laughed at me and with me, but it didn’t feel threatening. At the mention of girls, their faces would either grow blank and pale, or sick with disgust. Most of the time they liked to change the subject. But my own daughters sang in a children’s chorus and I wanted the boys to know that for the upcoming holiday concert, the girls were singing a Yiddish melody.

One Moishe said, “You mean, they sing 10 goyish songs, and then they learn one Jewish one?”

“What’s the difference?” said another one of the Moishes. “His daughters aren’t Jewish anyway.”

“I have a recording of them singing on my iPhone, listen.” “Please, Mr. Mayer, don’t play it, we can’t listen to girls singing.”

“Wait,” said the other one. “How old are your daughters?”

“Nine, almost 10.”

“Forget it, Mr. Mayer, forget it. They are too old.”

“Too old?” I laughed. “Too old for what?”

“A woman’s voice could be arousing, it’s not allowed.” “Arousing?” I screamed. “Nine-year-old girls!”

But the boys never tired of testing my Jewishness.

The seniors, who were good at avoiding work, decided one week that we would start each class with my reading a portion of the Torah. It was like studying for my bar mitzvah all over again. They hovered around my desk, and while I read they pointed to the words and helped me translate. They offered me snacks, and when I was able to say the correct blessing they applauded me.

“You’re a good Jew — see!” they would say. One of them took his high-crowned black hat from the closet and put it on my head.

“Now, Mr. Mayer, you’re looking good.”

“Yossi, give him your jacket, drape it across his shoulders.” With my iPhone they took photographs. I scolded them jokingly with a politically correct phrase I had seen circulating on Facebook, meant to chastise people who dressed up in stereotypical ethnic garb.

“Guys,” I said, “We’re a culture, not a costume.” They laughed: “We’re both!”

By November, I was worn down from carrying that heavy, torn textbook from class to class. I got Rabbi B’s permission to teach the play “Death of a Salesman” to both grades and he let me bowdlerize the text. It’s the story of a father and two sons, a dysfunctional family, and the failure of the American dream.

What could possibly go wrong?

As it turned out, bowdlerizing “Death of a Salesman” was not that difficult. Using white-out, I obscured anything I thought inappropriate. Wasn’t there something illegal about this? I wondered. I hadn’t read the play since teaching it five or six years earlier at a public high school, and I went through it page by page. There was a “damn” here, a “hell” there. A mention of Biff having sex for the first time had to go. Linda Loman’s stockings? Questionable. Maybe even a mention of “God.” Unfortunately, I missed a “bitch,” which caused endless grumbling among the students. We read aloud. Some of the ninth-graders enjoyed reading, and even argued about who would play whom.

After a week, we had gotten to about the middle of the play. I borrowed the video “Death of a Salesman” from the public library, a wonderfully depressing, black and white 1966 TV version starring Lee J. Cobb (formerly, Leo Jacoby of New York’s Lower East Side). At first, watching the film was a bonding session. Because they were not allowed to have computers, televisions or high-tech gadgets at the school, both classes huddled around my laptop computer to watch, and for them it was a treat. I was offered candy. For me, it was a respite. And, it seemed to be working. After this, I would find another play and we would watch that too.

Well, that didn’t last long. Rabbi B came to me privately.

“Please, no watching of videos, one of the boys complained,” he said.

“Complained? They loved it, there were a couple of ‘damns’ and ‘hells’ but overall it was a great experience for them.”

“Well, apparently while you were fast-forwarding the film, one of the boys saw the image of a woman, showing a bare shoulder to Willy Loman.”

“You’re kidding, right?”

“No, please, no more videos. It only takes one parent.”

I was beginning to understand why so much was forbidden. It was pretty simple: Whatever good might be gained from contact with the outside world couldn’t measure up to the potential dangers and damage it might cause. Nearly everything outside their proscribed world could be construed as a temptation away from God, and a threat to their existence.

Overall, the attempted discussions of the play were unsuccessful. The boys could not relate to Willy Loman’s failures. To them, he was just a crazy, pathetic old man, selling God-knows-what.They made comparisons between Willy and me.

“You’ve been teaching for 20 years, Mr. Mayer, what are you doing here? You wrote a book Mr. Mayer, can’t you do something else?” We joked about how I could write a play called “Death of a Schoolteacher,” and it wouldn’t be that far-fetched. Though, I told them, there was no plan to kill myself.

•

In the meantime, we started reading the screenplay of “12 Angry Men,” which the rabbi himself had recommended. It was a great idea, because all the parts in the script were for men. There was nothing to cut out — no women to speak of, no sex, no mention of religion. The story addressed the situation of a poor, young Hispanic man who is accused of murder and faces the death penalty. The case involves two eyewitnesses, an elderly man and “a woman across the street.” I tried to focus on the concept of “reasonable doubt,” which seemed like a good discussion topic. When the time came to write the essay, I gave them a choice of questions. One of the questions asked: If this were tried in a Jewish court of law, how would things be different? This prompted a discussion about the validity of women as witnesses.

In a Jewish court, a woman would not be allowed to testify, I was told. A woman was almost like a child and couldn’t be trusted. She would be too emotional to know what she really saw. She wouldn’t understand multiple points of view, it would be too complicated for her. When I tried to tell them that this was blatant sexism, someone said that I was questioning the rules and in turn accusing God.

On the first evening of Hanukkah, I was invited to participate in the candle lighting ceremony, which the students were left alone to conduct. It was in the basement cafeteria, the dreaded ninth-grade classroom. Because the sun set early during those late days of December, the ritual was to take place immediately after classes ended. One by one, students appeared in the cellar.

“Mr. Mayer, will you light?”

“Of course, I will light.”

“Will you say the blessings?”

“Of course, I will say the blessings.” It was nice. Each student had his own menorah, made up of small glasses for candles, which they filled with olive oil. They put on their black hats, and black jackets over their white shirts, and I was suddenly surrounded by a sea of black. When my yarmulke fell off my head, someone gave me his black hat to wear. Fox, a nudnik if I’d ever met one, was also the most excited that I was lighting the candles. I said the blessings and received a round of applause. When I went home that night it felt promising. At home my wife, a non-Jewish, non-believer in organized religion; my two daughters, who are being raised half-Jewish by exposure; and I each lit a different menorah. My daughters recited the blessings. With the colorful candles glowing, and holiday decorations strewn about, our home had a cozy, hopeful feeling. We planned on getting a Christmas tree after school the next day.

On the first full day of Hanukkah, the second evening for lighting candles, the boys invited me to a real Hanukkah party. They were even more hyper and restless than usual. So I sang the silliest Hanukkah song I could think of by Woody Guthrie, something about “latkes on your toes,” and then together we listened to it on YouTube. In return, they borrowed my iPhone and played me their favorite, “Candlelight,” by the Maccabeats, which — though none seemed to know — was a remake of “Dynamite,” a Top 40 dance song that my daughters and I often sang together.

“It’s a real song,” I told them, “Your guys just changed the words.”

Amid the commotion, one of the Moishes, Moishe Lanzman, a boy who looked like an embittered old man but who had turned out to be a fervent supporter of mine, asked, “Mr. Mayer, you lighting again today? You know, of course, it’s a mitzvah.”

“Am I lighting today? Of course I’m lighting today,” I said. “I am lighting twice today, like I did yesterday. First here, then at home.”

There was a momentary silence.

“Wait, what do you mean? You can’t light twice in the same night.” Moishe Lanzman filled three small cups with oil.

“I mean, I lit here, and then I went home and lit with my wife and children.”

“You mean they lit? They said the brachas — blessings?” He looked up at me.

Fox, who was balancing his too-small hat on my head again, gave Lanzman a covert poke in the ribs. “What’s the difference?”

“The difference is you can’t light the candles twice,” he repeated.

“No, it doesn’t make any difference — of course, he shouldn’t light twice — but his children aren’t Jewish anyway. So either way it doesn’t matter!”

Then, Yitzhak, the smart senior, who was more of a literal-minded stickler than the others, added, “His wife and his kids are goyim. Neither should light. It’s for your own good, Mr. Mayer.”

I took a few deep breaths. “You know what, guys?” I said. “I have to leave. I’ll light the candles when I get home. The truth is that my wife needs to pick up a Christmas tree.” Some nodded sarcastically, some cringed and recoiled in horror. “But don’t worry,” I said, “I’ll light the tree too. I’ll burn it down.”

One of the kids piped in, “We should burn down all the Christmas trees!”

Fox looked at me with his big teeth, a big sarcastic all-knowing smile on his face. My head began to tremble the way it had several months ago when they were inspecting my inside-out shirt.

“And since when are you my rabbi all of a sudden, Mr. Fox?” “He couldn’t be your rabbi,” Weasel added. “Mr. Mayer’s rabbi is probably a woman anyway.”

“No,” I responded, “He couldn’t be my rabbi because my kind of Judaism believes in tolerance and compassion.”

In the evening I lit candles at home, and we picked up a Christmas tree. I also got an email, offering me the position of “long-term substitute teacher of humanities” — a job I had interviewed for a few weeks before. The title was not so great; it reminded me of Willy Loman. But I would finally be out of here. Did I care? Would I miss the students?

“What a sad thing for the kids,” my wife said. “I’m sure their teachers quit all the time. And it’s not their fault.”

I wouldn’t miss teaching the classes, but I would miss interacting with the individual students. I thought of what one of the mothers emailed me after she’d gotten a complaint from the rabbi about her son’s behavior in my class: “I know it’s hard to believe, but almost all of these boys will turn out to be mensches — decent human beings.” I wondered about that. I believed they really would be decent to each other, but I also imagined that their tolerance for other people would not improve with age.

I gave Rabbi B several weeks’ notice, and told him I would stay till mid-January. We decided it best not to tell the students until a day or two before I was to leave. I had hoped the rabbi might say he was sorry to see me leave, or that I had done a commendable job in my four months, that the kids would miss me, or that yes, he had kind of expected me to leave. He barely looked up from his computer screen. Within an hour he had already posted my vacated position back on Craigslist.

On the Tuesday of my last week, I announced the news to my 10th-graders. At first they all applauded and cheered. Within seconds the word had spread through the narrow halls, up and down the stairways of the building. In the beit midrash, some even stopped praying. One kid jokingly asked me for a hug. And soon, their shouts of approval turned into a barrage of questions: Where was I going? Was it the rival Jewish school? Was it a goyish school? What kind of students were they? What would I teach them? Would I visit some time? Could we have a party on Thursday?

On Thursday, my last day, I came in feeling strong and free. When I arrived, several boys were shooting hoops on the dilapidated court outside, yelling for me to come and play. One of the four Moishes — the most likeable of the lot, the one I called Smart Moishe — was unloading cartons from a van when he saw me. He quickly dropped the boxes, and in his black shoes, in a semi-lurking walk approached me.

“Mr. Mayer,” he spoke softly. “Can you keep a secret?”

“Depends. I suppose.”

“Please, if I tell you, you can’t tell anyone.”

“Well, no guarantees, but OK, tell me anyway.”

“I have a copy of your book, the one you wrote, and would like for you to sign it for me before you leave. I will give it to you later, but please don’t mention a word, please.”

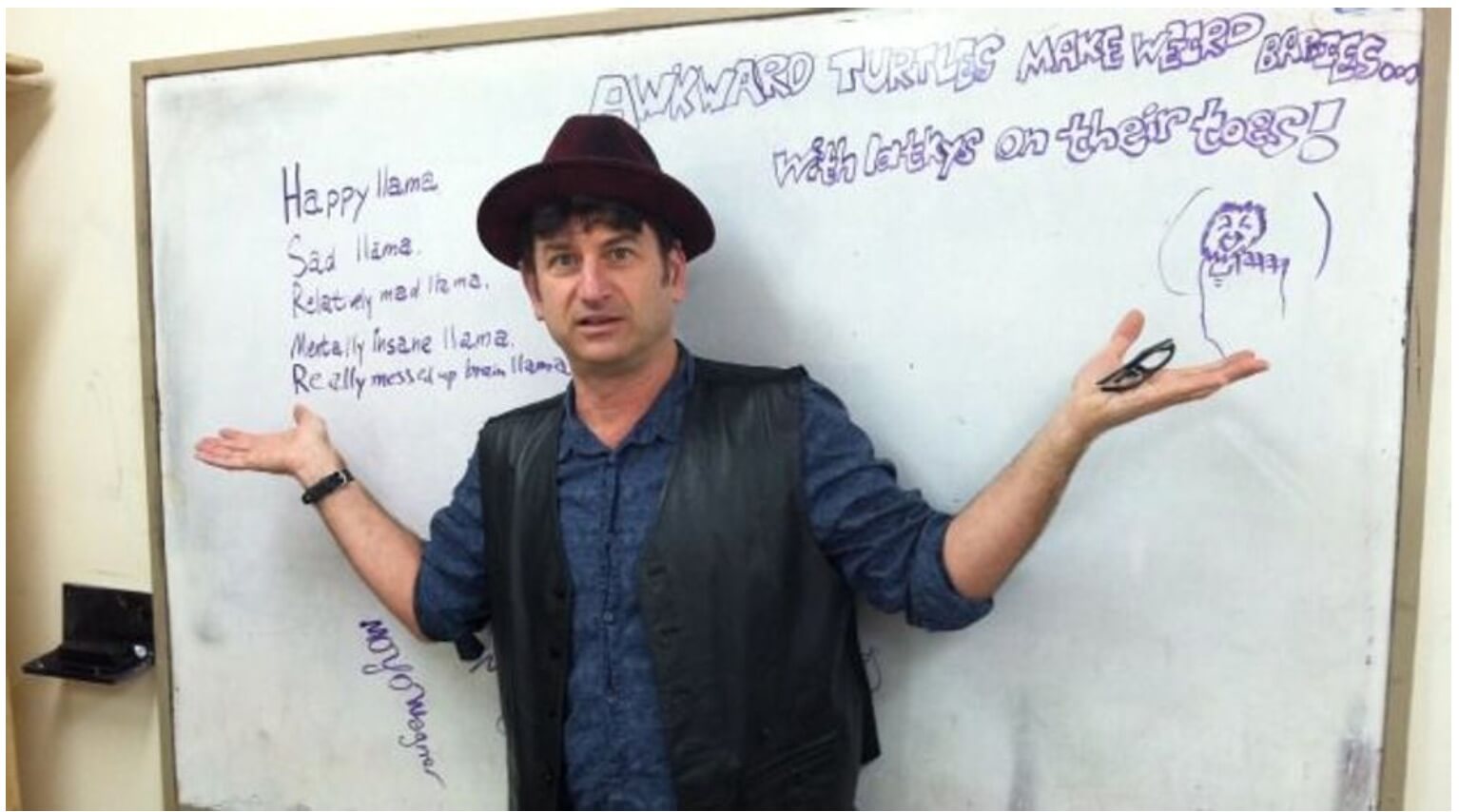

Meanwhile, the 10th-graders had spread a white, plastic tablecloth across their desks, and ordered kosher pizza for my going away party. In my honor, someone wrote on the whiteboard in purple marker all the lyrics to “Happy Llama, Sad Llama,” and drew a cartoonish picture of a laughing latke on someone’s toe. I promised to visit for their next holiday party, on Purim, in March. I really meant it.

The ninth-graders, who had carried boxes down to the basement, had prepared their own farewell party. But as I made my way, Smart Moishe, now blushing, asked me to follow him to the dark hallway of third floor, where I had never been. Once there, he ducked into a room, and quickly handed me a black, plastic bag whose ends had been folded over and knotted.

“It’s in here,” he said. “When you’re done, put it on the shelf downstairs, where the hats are, in the main lobby, and push it into the corner. Don’t let anyone see you.” I nodded, as he lightly pushed me toward the stairs.

The ninth-graders were lying in wait in the cafeteria. Some were standing on red vinyl chairs. Others cleared chairs to the side of the room. And when I arrived they let out a series of cheers.

“Mr. Mayer, Mr. Mayer! Look, we bought all this — pretzels, chips and soda — for you. And Weasel’s mother even made you brownies.” One of the boys plugged in an electronic device to a set of small speakers and began to play some bass-driven Hebrew song.

“It’s time to dance, Mr. Mayer.”

“But I’m not dancing,” I said. “I don’t know how to dance, not the way you guys do.”

“Oh, come on, we’ll teach you.”

About eight boys gathered in a circle in the center of the small underground hideaway. They were already holding hands, eagerly waiting for me to join them in a freylekh. “Come, Mr. Mayer.” A place opened in the circle for me to enter the chain.

We began circling to the right. We snaked around between the basement girders and chairs. We completed several rounds, and then Weasel’s sweaty palm let go, breaking the chain, to dance by himself in the center — to show off, I thought. The music was loud, very loud now. Perhaps he would squat close to the ground, fold his arms across his chest, and kick each leg out in a Jewish rendition of an old Cossack dance. But instead, he grabbed both my hands and pulled me inside with him so that we could swing around together. The circle around us clapped in unison, until one of the Shlomos cut in. We were now three.

At this point, the red fedora I had been wearing for the occasion fell off my head. Shlomo picked it up and replaced it with a yarmulke. I had my right hand on my head, holding it in place, the other grasping his hand as we continued to go around. As if I had created a new dance step, Shlomo and Weasel imitated me, putting their right hands on their heads, and with great animation, tilting, bobbing and weaving. This went on for several minutes until I ran out of breath, and the music stopped.

But the boys had just started. Weasel introduced another song for me. He nodded — a slow number, something in Hebrew — something sentimental. It seemed rehearsed. Eight boys side by side — arms around shoulders and waists, all smiling. As I photographed, they began to sway back and forth to the melancholy rhythm. I switched my iPhone camera to video recorder. The words were now in English as they sang: “The spark in your soul is still there, it’s never too late, Mr. Mayer. It’s never too late.”

A second group of boys stacked themselves into a small pyramid while chanting, “Na Na Na, Hey Hey Hey, Goodbye.” The original group backed me into a corner, clapped over their heads, and wagged scolding fingers at me as they sang: “You are still a Jew. You are still a Jew. Mr. Mayer is a Jew. He is still a Jew.” After the song faded, several of the boys handed me their phone numbers and told me to keep in touch.

Upstairs, the 12th-graders who had spent the last four months convincing me that high school seniors weren’t ever expected to do schoolwork, were waiting to present me with a gift. It was a four-cornered, open-necked undershirt with hanging, twisted tassles — tsitsis — intended to remind me of my religious obligations as a Jew.

“It’s not a big deal,” Yitzhak the arbiter of Jewish law told me. “You wear it like an undershirt, no one will even see. And besides, in the winter, it will keep you warm.” But I knew I would never wear it. I shook my head and apologized. “OK, but for us, now, please say a blessing, and wear it this once.” I agreed. I said the blessing. I slid the garment over my head as he clicked my camera.

“The hat, the hat, put his red hat on,” someone suggested. “And the black leather vest.” There was a pause. And then Yitzhak looked at the photo and proclaimed: “Mr. Mayer — a fine-lookin’ Jew.”

Yes, although we disagreed on just about everything — from our interpretations of Judaism to our attitudes about the world — they still considered me as part of the fold. Perhaps in this way, they were more tolerant of me than I was of them.

It was time to leave. One of the boys handed me a folded prayer to keep in my wallet.

“I guarantee if you keep this with you, it will keep you safe.”

They gathered around me as I took off the white shirt. I exited the classroom into the vestibule. Smart Moishe had surreptitously taken my book wrapped in the black plastic bag off the hat shelf. He nodded at me over his shoulder and then ran down the stairs into the street. He was one of the few who I thought might be saved. And I’m pretty sure he was thinking the same about me.