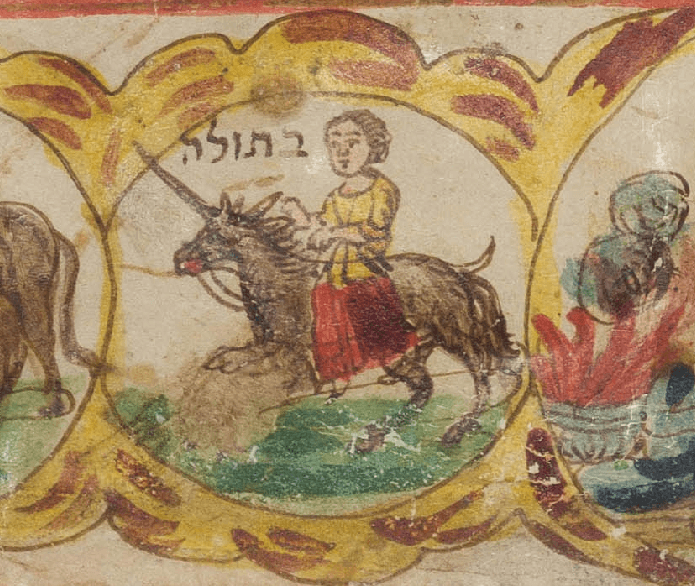

What’s a Christian unicorn like that doing in a Jewish marriage contract like this?

A new exhibit about the Jews of Corfu offers some surprising insights into Jewish art and practices

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

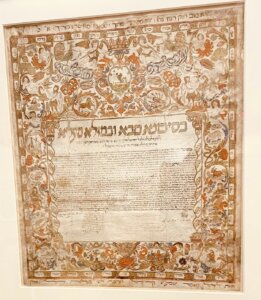

When Abraham Shaptei wed Esther Kiridi on a Wednesday evening in 1820 on the island of Corfu, they displayed their richly illustrated ketubah, or marriage contract, for their guests to admire. Now, more than 200 years later, it’s not the abundance of gold leaf or the intricate vegetal tendrils that draws one’s eye. It’s the unicorn.

“People are very surprised to see the unicorn. The unicorn is Christian, but unicorns do show up in Jewish art; in the margins of Hebrew manuscripts and texts, on silver. Most often it’s a unicorn confronting a lion as a symbol of Jewish messianic hopes,” said Sharon Liberman Mintz, curator of Jewish art at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America.

Yet, unicorns, the zodiac and endless love knots feature prominently on the 10 ketubot displayed in “The Jews of Corfu: Between the Adriatic and the Ionian,” a joint exhibition between Columbia University and the JTS Library. In addition to the ketubot, the exhibit features prayer books and communal and legislative documents.

The Jews of Corfu

Forty miles long, Corfu lies between the Adriatic and Ionian Seas. From the 12th century through 1944, when the Nazis sent 1,800 Corfu Jews to Auschwitz, two distinct, albeit small, Jewish communities called it home.

The first to settle there were the Romaniote, or Greek-speaking Jews, from Byzantium. The Italian-speaking Jews arrived in the late 14th century when the Republic of Venice seized control of the island.

The two communities didn’t mingle much. In fact, there was a lot of tension between them. The older Greek community remained insular whereas the Italian community welcomed other Jewish communities.

Over the next few centuries, hundreds of Jews fleeing persecution in Europe found refuge on the island. In 1864, Corfu became integrated into the modern Greek state and Jews of Corfu were given equal rights with the rest of the population.

About 6,000 Jews lived on Corfu at its peak.

The population started leaving in droves in 1891 following a vicious blood libel. After Rubina Sarda, a young Jewish girl, was murdered, local Christians accused Jews of killing her and using her blood for ritual purposes. The Greek police helped fuel the conspiracy and ultimately a mob killed over 20 Jews.

Order wasn’t restored until the British Navy, which had been anchored offshore, convinced the Greek government to send troops to stop the violence.

“It was the beginning of the end for the island’s Jews,” Margolis said.

Zodiac and gold leaf

Vines surround small inserts of the 12 zodiac signs as well as jewel-toned pigments and an abundance of gold leaf reflect the Venetian aesthetic of the time. So too do Aramaic words found at the top: be-siman tava u-be-mazla m’aliya, according to Michelle Margolis, Columbia’s Norman E. Alexander Librarian for Jewish Studies.

“Both the Hebrew and Aramaic word for the sign of the zodiac is mazal, which translates as luck. It’s literally wishing ‘good signs,’” Margolis said.

Like any tightly knit community, Corfu had its share of drama.

One tract concerns an international rabbinical dispute about whether one can sing the Shema; legislation addresses the yellow badge Corfu Jews were required to wear. There are also several illustrated prayers of penitence as well as a booklet dating from 1624 that includes 27 testimonials supporting one man’s right to bear arms.

A ketubah from 1762 enumerates the bride’s dowry and stipulates that the groom must promise not to take another wife; if he does, he must give his first wife a proper divorce.

A ketubah created for the 1725 wedding of Moses Mazza and Stamou Vivante shimmers with the abundance of gold leaf. Even more arresting are the satyrs, reclining nude water nymphs and winged cherubs nestled between the curling leaves.

“It’s rather hedonistic, but also typical of ketubot from Corfu during this period,” Mintz said.

Included on this ketubah is a paragraph in Hebrew that says five days after the wedding, the groom verified that the bride was a virgin.

Confirming a bride’s virginity was particularly important for Jews living in Islamic countries, Margolis said.

“It actually protected the bride. The groom couldn’t later claim she was damaged goods,” she said, adding that this codicil is only found in the ketubot of Corfu’s Romaniote communities.

The first U.S. professor of Jewish history

The exhibit is a tribute to the work of the late Salo Wittmayer Baron. Considered the first U.S. professor of Jewish history, he taught at Columbia from 1930 until 1963.

After Baron immigrated to the United States in 1933, he arranged the purchase of 700 manuscripts from David Fraenkel, a bookseller from Vienna. Included were 80 manuscripts and 40 printed books relating to Jewish life in Greece.

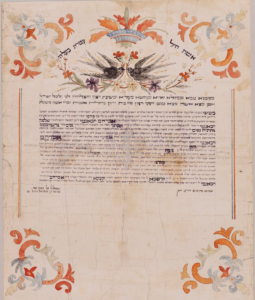

Of all the ketubot on display, the one from 1944 is the most poignant.

It was created for Abraham Vivante and Esther, daughter of Nissim, on May 26, 1944. Two weeks later the newlyweds were among the 1,800 of the island’s remaining 2,000 Jews sent to Auschwitz. Today only 60 Jews live on Corfu.

“This is not about the Holocaust, but you also can’t help but ask what did we lose when you look at how amazing this culture is,” Margolis said.

The exhibit is on display in both Columbia’s Butler Library and the Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary. At Columbia, because of COVID-19 protocols, visitors must make appointments in advance. The exhibition at the JTS Library is open to the public Monday through Thursday 9-7 , but visitors must bring proof of vaccination.