He painted like nobody else — so why haven’t more people heard of Sam Szafran?

The self-taught son of Polish Jewish immigrants is now the subject of a major retrospective in Paris

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

PARIS —You’ve probably never heard of a French artist named Sam Szafran. You likely aren’t aware that this relatively little-known figurative painter was born in 1934 in Paris, that his birth name was Samuel Berger or that his parents were Polish Jewish immigrants. Or that during World War II he was hidden in the Loire Valley and in the south of France, and that he was later sent to the Drancy transit camp outside Paris but was liberated by the Americans, and that much of his extended family died in the Holocaust.

This artist, who specialized in pastels and watercolors, is now the subject of a major exhibition at Paris’ renowned Musée de l’Orangerie, home to Claude Monet’s remarkable and inspiring “Water Lilies” and masterworks by Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso, Pierre Auguste Renoir and Chaim Soutine.

“Nobody paints like Sam Szafran paints,” said Julia Drost, co-curator of the exhibition along with Sophie Eloy.

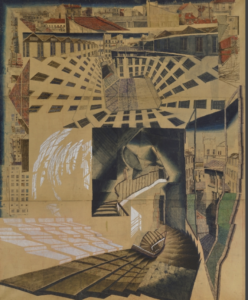

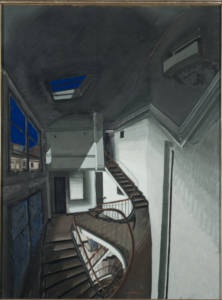

His work is “very rich in details,” Drost said. “This is very special. You do not find that very often in the art of the 20th century. He loves the detail, and if you have a close look at his paintings, you find details everywhere.”

Szafran died three years ago. The last show he had in a Paris museum was in 2000 at the Musée de la Vie Romantique. It was, according to Drost, “a small but wonderful show.”

“I think you can count his shows in museums on one hand. So maybe now the time has come to show him in a big space,” she said.

Szafran was the son of “immigrants who arrived in Paris at the end of the 1920s,” Drost told me. He was the first generation of his family born in Paris.

As an adult, she continued, Szafran “called himself not French or Jewish. He called himself Parisian.” But when he was 6 years old, and Germany invaded France, the fact that he and his family were Jewish mattered greatly.

“When the Second World War broke out, he was hidden in the countryside. His father went into the French army and then was deported to Auschwitz. And he died in the camp. The family did not even know when and how. He disappeared. It was very hard for them.” The same fate awaited many members of his extended family.

The first people Szafran stayed with, in the Loire Valley, did not treat him well. He fared better with the second, a family of Spanish Republicans who had fought the fascist Francisco Franco.

“When the police came, Sam Szafran told us, because he was a blond young guy with blue eyes, they were told he was the son of the concierge,” Drost said. “This was how he was saved from arrest.”

After the liberation of Paris, the Red Cross sent him to Switzerland, where he began painting. Then he, with his mother and younger sister, who had also survived, spent some years with family members in Australia.

“Sam Szafran: Obsessions of a Painter,” includes about 100 items, among them more than 60 paintings, as well as archival material from his studio.

Szafran was indeed an obsessional painter, an obsessive personality, “obsessed by his topics and his painting,” a trait that can be directly traced to his difficult and complicated childhood, said Drost, who met Szafran about a dozen years ago and worked with him for many of those years, on his catalog and on a previous show in Germany.

“I think it all goes back to feelings of loss and abandonment during his childhood,” Drost said of the artist’s obsessiveness. “Art becomes a kind of second reality, where he can set an anchor.” Szafran explained it himself, she said. “He said that if you give a sheet of paper to a child, and you give him a pencil and he starts drawing, he’s going to become calm. This is how it works in the work of Sam Szafran. I think he needed that work to do to find courage in life and to get settled.”

Szafran was largely self-taught. “By 1951, when he was back in Paris, he had hardly been at school in his life,” she said. “He had had to hide from the Nazis starting when he was 6 years old.”

But he was very interested in learning. “He started having discussions with poets and painters and philosophers in Saint-Germain-des-Prés” on the Left Bank “and in the quarter of Montparnasse.”

Jo Schaffer, professor emerita of art and art history at the State University of New York College at Cortland, knew Szafran in his starving-artist days in the1950s and early ‘60s. “Sam and I were students together in 1954-55,” Schaffer recalled in an email. “Day after day I would treat him to a coffee at The Select because he didn’t have a penny to spare. In 1960-61, when my parents were in Paris for a Fulbright year and living on the Boulevard Raspail, I introduced Sammy to them. He was living in a one room unheated whatever. My mother would have him come weekly for a hot meal and a bath, and when they left, my dad gave him his winter coat and other clothing.”

Szafran became obsessed first with the studio, then staircases, and then with foliage — all of which are seen extensively in the exhibition.

Drost emphasizes “the interiority in his work — just concentrating on one topic, and coming back to it again and again and again, not going outside.”

The medium he chose also became his obsession, she said. “When he started working in pastels it was kind of very old-fashioned, because nobody worked in pastels in the early 1960s. A friend offered a box of pastels to him,” and then he discovered handmade pastels.

“He found them very tender. It became a kind of obsession,” she said, adding that the difficulty of mastering the nuances of colors in pastels became a “technical obsession” for him, similar to one he later felt with watercolors.

For most of his life, Drost said, Szafran did not care at all about his Jewish heritage, Drost said. As a child, he went regularly to synagogue with his parents and other relatives. But then, she said, for a long time he abandoned his religion — until later in his life, in the years before his death, when he began to talk often about his childhood memories.

He wound up changing his last name from Berger to Szafran, the surname of his maternal grandmother, to honor the woman who mainly raised him, Drost said, for whom “he had so many tender feelings.”

“He was an individual artist who needs to come to light,” Drost said. “It will be a discovery, I think, for many, many people.”

“Sam Szafran: Obsessions of a Painter,” runs through Jan. 16 at the Musée de l’ Orangerie