Was Morris Hirshfield’s Jewishness responsible for his fall from grace in the art world?

A new retrospective on the surrealist artist grapples with his obscurity after a dazzling debut embraced by Picasso, Duchamp and Peggy Guggenheim

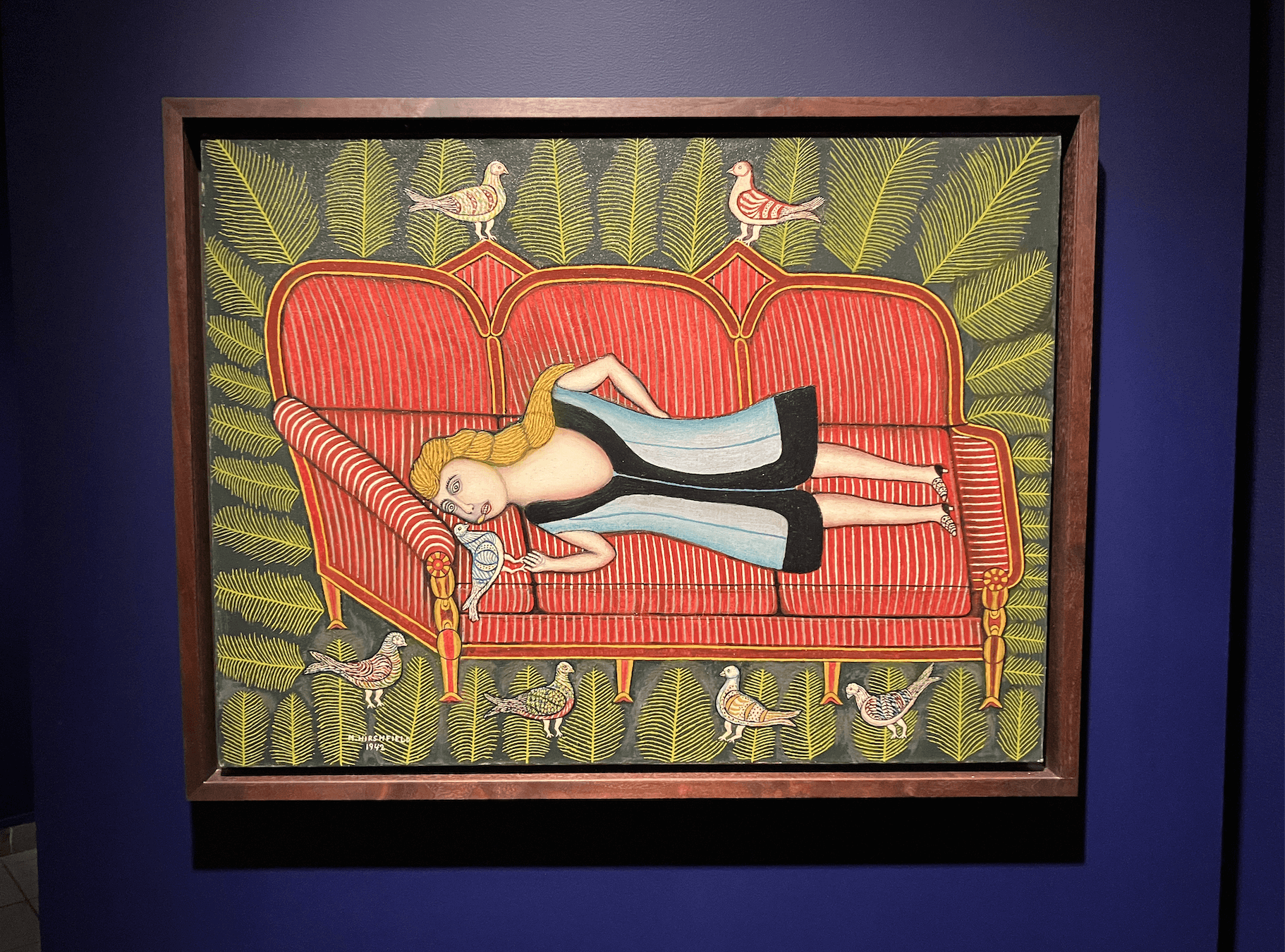

“Girl with Pigeons” is considered one of Hirshfield’s masterpieces. Note the woman’s delicate heeled shoes. Photo by Mira Fox

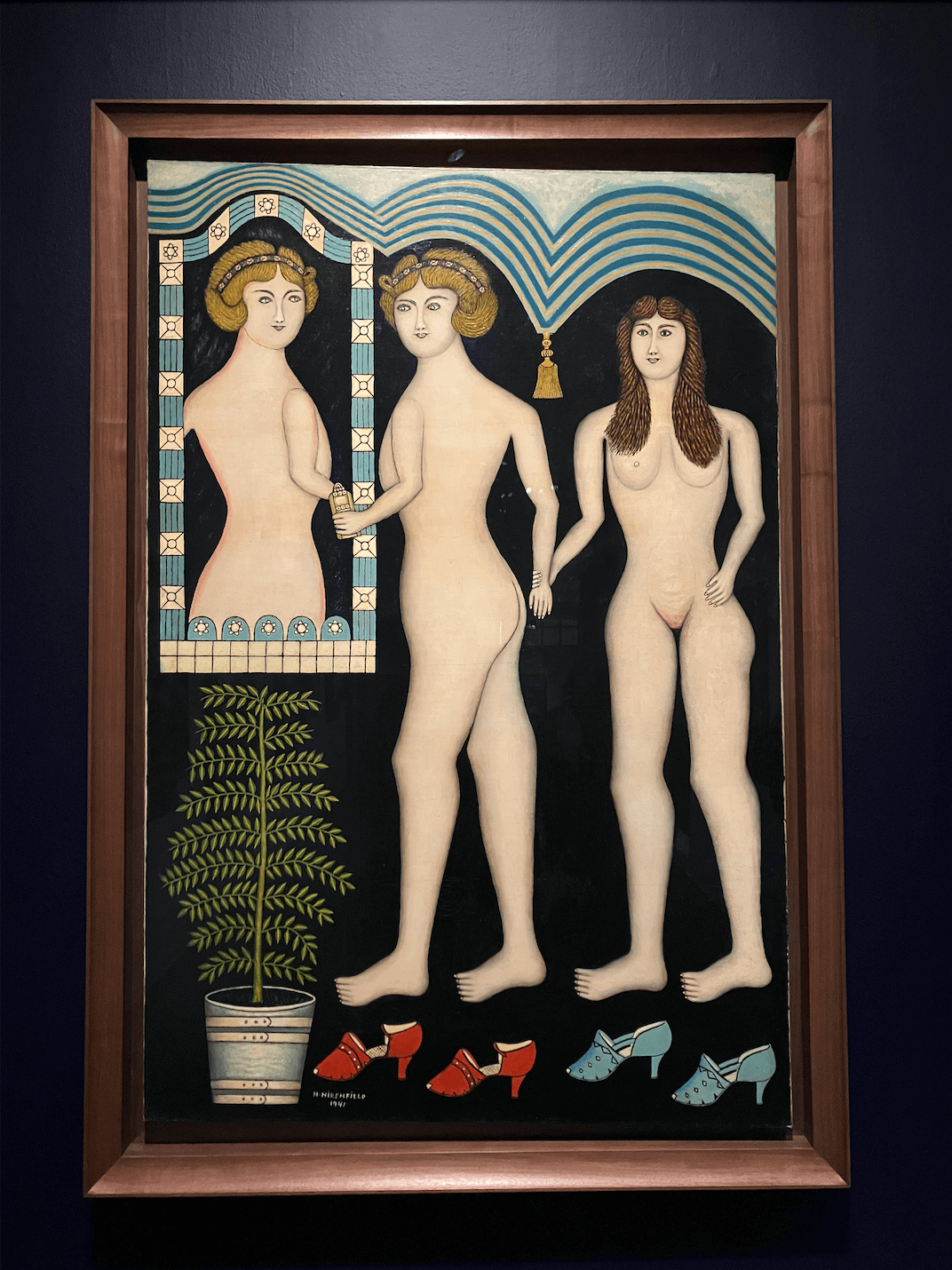

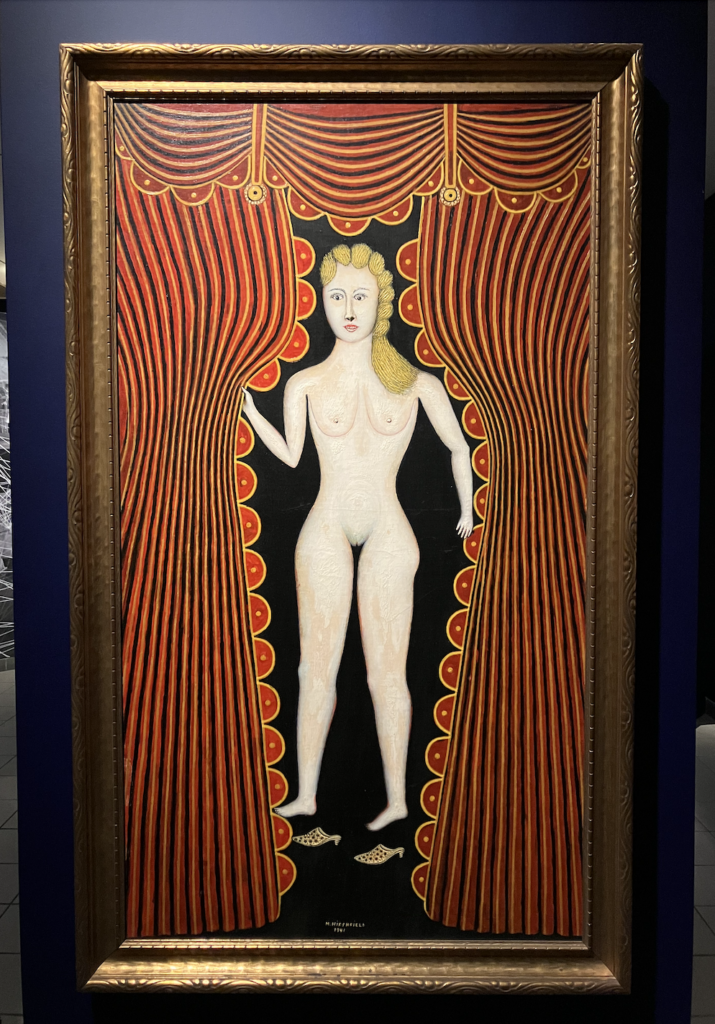

Morris Hirshfield’s vibrant, stylized paintings often feature intricately embellished slippers. They adorn the feet of a lady arranging flowers in one painting and are worn by a female figure lying, facedown, on a couch in another. One pair even sits near the feet of a nude woman peeking through carnival-striped curtains.

The slippers are a hint at the career that dominated the majority of the painter’s life: shoemaking.

A new exhibit at the American Folk Museum in New York, “Morris Hirshfield Rediscovered,” explores the painter’s entire career, including his time in the garment industry, also known as the “shmatte trade.” A case of slippers, recreated by artist Liz Blahd from Hirschfield’s patents, occupies a whole corner of the exhibit. It is the first retrospective of the artist’s work since his solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1943.

Until his mid-60s, Hirshfield, who was born in Poland in 1872 and immigrated to New York at age 18, made women’s coats, dresses and shoes. Living in Jewish communities in Brooklyn, such as Borough Park and Bensonhurst, he only took up painting in the last decade of his life, when poor health forced his retirement; he painted his first two pieces over artwork his wife had bought for their house.

Those works, which already demonstrated what would become Hirshfield’s distinctive style of bold patterns and flattened perspective, caught the eye of prominent gallerist Sidney Janis.

For a brief period, the Jewish painter was embraced by the surrealist movement: His work was featured in exhibitions on Surrealism alongside luminaries such as Frida Kahlo, Max Ernst and Marcel Duchamp. André Breton and Pablo Picasso touted his art. Influential art collector Peggy Guggenheim even bought a piece for $900 — over 10 times more than she paid for a now-famous painting by René Magritte, who was, even then, a bigger name.

But then, as the American art world lost its interest in naive art and primitivism, he fell into obscurity. After his MoMA show, critics mocked Hirshfield, dubbing him “The Master of the Two Left Feet,” thanks to his strangely rendered figures. Though people in the folk art world continued to discuss his work, Hirshfield was left out of discussions of modern art and the surrealist movement.

The new exhibit emphasizes the lack of respect given to Hirschfield by recreating a section of his MoMA show. In the text accompanying one painting, the references and symbolism are thoroughly detailed: Stars of David adorn a mirror, tassels are likened to a tallit and outlines evoke the Torah. But, the text adds, the artist was “entirely unaware of the presence of these elements in his work.”

“Almost none of the significant happenings” in Hirshfield’s work, the original exhibit went on to assert, “are accomplished with the direct intention of the painter.” Even a Yiddish pun, which one might assume Hirshfield might have had the requisite tools to understand given his immigrant background, was made “unwittingly.”

In framing Hirschfield as primitive, critics directly invoked his ethnicity and religious practice. In 1930s and 1940s America, Jewish immigrants, especially those from Eastern Europe, were still seen as an Other. A Newsweek article on his MoMA exhibit characterized him as living “in the Wilds of Brooklyn” — a faraway land occupied largely by, of course, Jews.

Hirshfield’s Jewishness is, indeed, a large part of his work. The artist, who normally painted 10 hours a day, kept Shabbat and didn’t paint on Jewish holidays. While many of the women in his paintings are scandalously nude — except for their shoes — he never worked from live models for fear of outraging his community. Instead, he worked from the same mannequins he once used to create clothing.

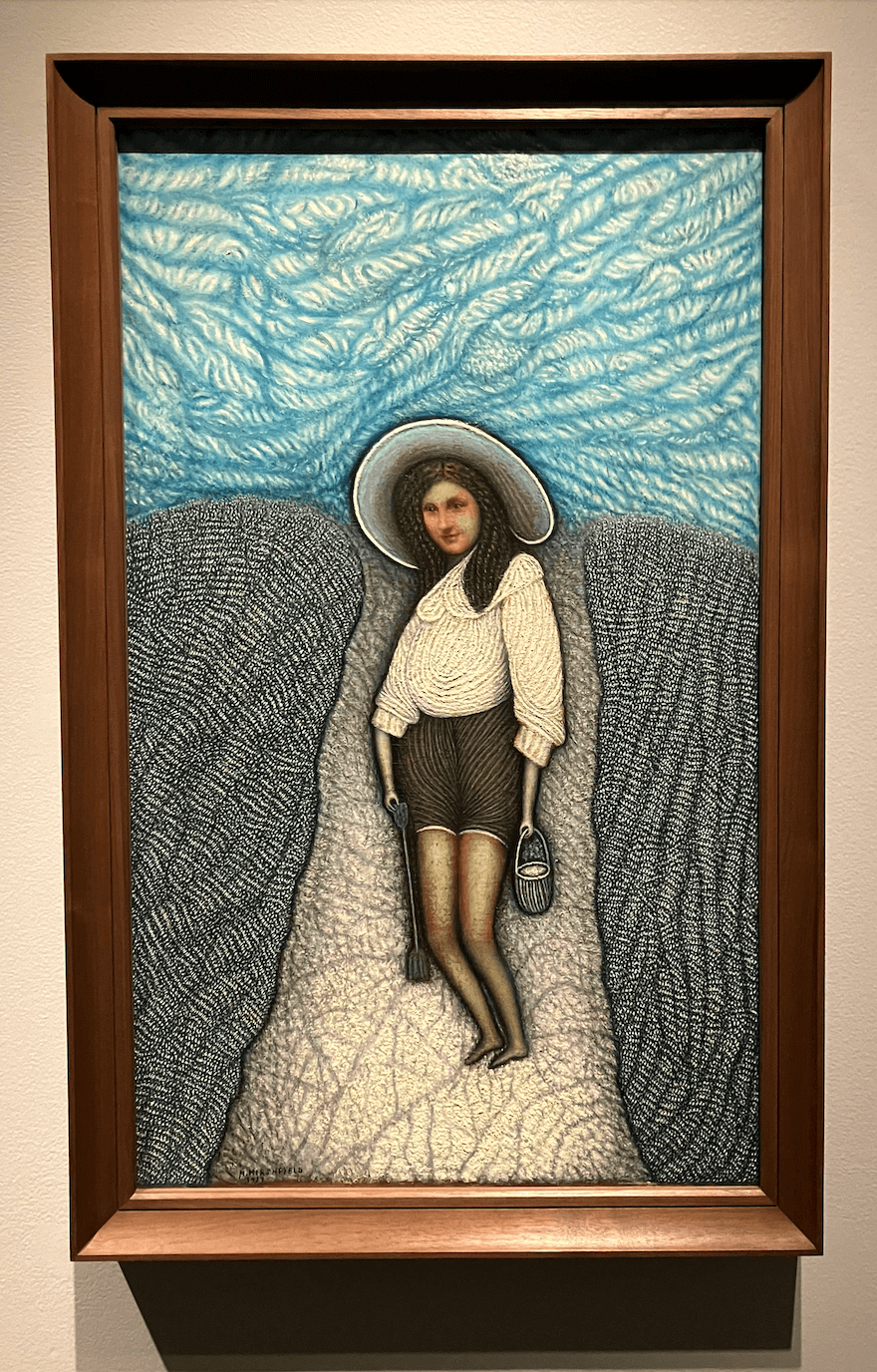

His cultural milieu is woven into his work. The textiles he worked with in the schmatte trade reappear in the rich textures of his paintings, many of which reach into the third dimension thanks to thickly layered paint. A wooly, knit sky soars behind a pot-bellied tiger and many of the women in his paintings appear to have hair made out of yarn. Vibrant floral patterns — on a dog’s coat in one painting, on a bird’s wings in another — evoke matryoshka dolls.

Religious themes show up overtly, for example in a painting of Daniel in the lion’s den or one of Moses and Aaron. Another, of a truncated Christmas tree flanked by cherubs, evokes a struggle against the dominant religion’s observance.

Looking at Hirshfield’s striking paintings, it seems unlikely that his work was as “primitive” and unconscious as his contemporaries believed. Even his distinctively stylized animals — dogs with oddly elongated snouts, flat-faced cats, strange bodily proportions — evoke stylized medieval illuminations and reveal a familiarity with art history.

The new retrospective rescues Hirshfield from obscurity and gives him the respect he deserves. It grapples with the contrast between the European surrealists who embraced the artist and the Americans who dismissed him as a “novelty act.” But it does not fully contend with the role the artist’s Judaism played in both his paintings and his critical reception.

Just as it was an intrinsic part of his life, Judaism is woven into every aspect of Hirshfield’s work. Biblical subjects as well as references to Jewish industry, history and culture appear in nearly every painting. His Judaism is even, in part, responsible for his dismissal from the modern art world.

Morris Hirshfield’s body of work — nearly 80 paintings and hundreds of drawings and sketches, created over less than a decade — deserves serious consideration. His Judaism does too.