The real Lou Reed was a lot funnier than you’d think

The purportedly cantankerous Jewish rocker wanted to be remembered for his sense of humor

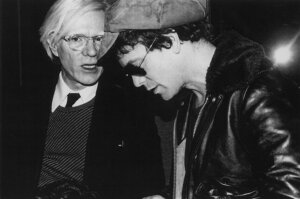

Lou Reed, circa 1981. Photo by Getty Images

The last time I saw Lou Reed in concert was at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art in 2009. Reed, then 67, sat on a chair stage left and played electric guitar and synthesizer, accompanying his wife Laurie Anderson, who was playing violin and synthesizer and singing with a vocoder.

Their sound veered between a cacophonous storm and disquieting ambience, like the creaking of a ship’s masts. There was no banter between them, little chat with the crowd. They wove 13 or so stories and songs together. One piece bled into another. Noise gave way to calm and then it reversed itself. There was no applause until the work was completed. Then, lots.

Reed and Anderson got married in 2008. One of their bonds, Reed told me, was that she was as much a gearhead as him. “She’s into effects and keyboards and all that; I’m into guitars and — not really extreme effects, but reverb and all that,” he said.

“What we do more than that is play together. Melodic and heartfelt,” he said.

Lou on meat cleavers and laser beams

Reed left the planet nine years ago this Oct. 27 at age 71. The first time I interviewed the influential Jewish rocker was in 1980. I asked what it was people most misunderstood about him.

“I don’t think people realize the sense of humor that’s running through these [songs],” he said. “To say my sense of humor is dry is in itself a dry joke. I think I’m very funny. I find most things very funny.”

He did allow that humor was, often, very dark.

That interview came at the dawn of the Reagan era and the fear was out there that the Cold War would become a nuclear conflagration.

“We’d all be ashes,” Reed said. He had just been reading U.S. News & World Report and what he termed “their annual end of the world issue” and he likened the anxiety of the times to the Bay of Pigs incident.

“Those of us who were in school” — Reed was at Syracuse University studying film and drama, being mentored by poet Delmore Schwartz — “were all ready to hop in cars and drive to the mountains and hide. Wasn’t everything going to end then?”

“If you sat down and seriously thought about things,” he said, “you’d drive yourself nuts. You’ve got to remember: This is New York, where a few weeks ago a guy got shot with a bow and arrow and there’s a guy running around with a meat cleaver down on the subway. What can you say about that?”

I said I wasn’t sure. But the question was really rhetorical.

“I think it at least shows some innovation on physical assaults on the citizenry — going back to more primitive weapons,” Reed said. “Now, I would find it perhaps scary if they found out that somebody were laser-beaming people to death in the subway. A guy like that would be hard to catch.”

When it stopped being fun

Lou Reed first came to acclaim, if not widespread fame, with the Velvet Underground, which formed in 1964. They came to be part of Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable, Warhol’s Factory scene of musicians, actors, artists and models. (The German-born model Nico sang on their first album.)

The Velvets dressed in black, wore dark sunglasses, looked dour and made disturbing music. They were not a band made for the peace-and-love flower-power hippie era and they never sold many records; their success was largely posthumous. But when the hippie era slipped away and punk rock roared in — with that joyous nihilism, minimalism and rebellion — the Velvets’ profile rose. Numerous bands cited the Velvets as inspirational.

“If it is true,” Reed told me, “it’s very flattering.’”

As Reed’s solo career blossomed, there were those who saw the Velvets as Reed’s heyday and Reed’s subsequent solo albums as lesser work. I asked him if the Velvets legacy ever became a burden.

“Not really,” he said. “What could be a cooler thing to be a member of? It’s like playing for the New York Jets when Namath was there. And every lyric that was ever sung by the Velvet Underground was written by me.”.

The Velvet Underground itself — Reed, his key partner, multi-instrumentalist John Cale, guitarist Sterling Morrison and drummer Moe Tucker — reunited for a European tour in 1993. There were plans for an American tour, but Reed and Cale had a falling-out that derailed those hopes.

“We said we would do it till it wasn’t any fun,” Reed said of the reunion. “At a certain point, it didn’t become fun — we all disagreed [on issues] — and we all said, `We don’t have to do it.’ So, we agreed to disagree and went our separate ways.”

Everything was fair game

Reed, like many songwriters, drew from his own life. Certainly, parts of “Heroin,” “I’m Waiting for the Man,” “Kill Your Sons,” “Standing on Ceremony” and “My Old Man.” Certainly, some of the albums such as “Berlin,” “Songs For Drella – A Fiction” and “Magic and Loss.”

“Berlin,” released in 1973, was a tour de force, a monster, a haunting, stark-but-lush concept album about two equally unsympathetic characters — a couple caught up in a web of drugs, sex, sadomasochism, betrayal and, finally, the woman’s suicide, which is greeted with a shrug by her lover. It was not pretty, but was grimly compelling, musically beautiful. He always liked playing a batch of its songs in concert.

Commercially, Reed considered that album a “massive disappointment.” “I thought the people who liked me for real would love to see that particular thing done live,” Reed told me. “I wasn’t kidding. It’s one of my favorite albums.” In 2008, he recorded a live album of “Berlin” at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn.

In 1989, Reed released “New York,” his grittiest effort in nearly a decade and his best since 1978’s “Street Hassle.” It was not a celebration of his town. He dealt with the evils of crack, the corruption of patriotism, the selfishness of America, the horror of Vietnam, the Louis Farrakhan-generated rift between Jesse Jackson and many members of the Jewish community. Also: poverty, drug addiction, racism, police brutality and child abuse.

“They’re the kind of topics that, unfortunately, are always going to be with us,” Reed said. “All you have to do is look outside. It’s not that way every day, but it’s always in the back of your mind. You’re always watching.”

The recording is tough and terse, boasting a thick, yet sparse, rhythmic two-guitar sound. Reed’s voice is low and guttural, shot full of lacerating wit and brutal truths.

With a 58-minute run time, “New York” was a record Reed said he intended to be heard as a movie is viewed: in one sitting.

“I’m not making disposable records,” he continued. “I’m trying to make one you can play five years from now.”

Reed was a musician and lyricist who thought like a short-story writer or novelist: He used what he experienced or observed and made it part of his art. He created characters like Jane the clerk and Jack the banker in “Sweet Jane,” Candy in “Candy Says” and the many Jims who have populated various songs.

“I know from personal experience that everything I encounter is fair game,” Reed said.

Reed maintained that he’d always written, first, to please himself. He said that he made rock ‘n’ roll for adults, not kids: “I can only hope there are enough grown-up people out there that want to hear something meaningful along with all this other stuff out there,” Reed said. “There’s certainly room for a lot of different kinds of things and I hope there’s room enough for my little thing.”

He said he believed that his lyrics also worked as poetry — “The bulk of them are meant to stand alone. That was the raison d’etre. The fact that there’s some rock going to it, that’s great.”

While some of Reed’s work seemed intensely personal, he told me that most songs he wrote were “not totally autobiographical.”

“It’s more of an amalgam of people,” he said, adding that even songs he sang from a first-person point of view should be regarded as if they’d been written from the third person.

“They’re very personal, done with a great deal of distance,” he said. “I try to keep myself invisible.”

Why art shouldn’t be like guacamole

Reed wrote standalone songs, but sometimes those were woven into conceptual albums, the best being the aforementioned “Berlin” and 1992’s “Magic and Loss.” In fact, in terms of tragedy and narrative structure, the latter recalled the former.

“It’s a direct descendant,” said Reed. “You’re telling them a story. It’s illustrated with music; with the best lyrics I could write. It’s an hour’s worth of music about a subject where you’ve got a beginning, middle and an end. I feel I can go up against a novel or a stage play or a movie easily.”

Though Reed was proud of “Magic and Loss,” he was frustrated by its reception. “I keep getting told, `This is too depressing,'” Reed said. “`It’s about death and it’s depressing.’ You know, I must say if you look at it that way, `Hamlet’s’ synopsis would seem pretty down, too. ‘Macbeth’ would seem pretty awful.

“I think of `Magic and Loss’ as about love and friendship, and it’s a very up thing. It is very emotional, also. These are not bad things. And I don’t see why a contemporary work of music can’t contain all these things. But when they do contain these things, you’re thought of as being too cerebral, or too down.

“I remember reading this book by Saul Bellow where he was quoting Walt Whitman and he said, ‘Until Americans and American poetry can deal with death, this is a country that has not grown up.’ There might be something to be said about that.”

Over the years, Reed and I talked about musical good times, too, from the simple to the complex. He was not averse to, well, fun, as can be seen in songs like “We’re Gonna Have a Real Good Time Together” with the Velvets, and “I Love You, Suzanne” and “Egg Cream” as a solo artist.

“I like to have a broad palette,” he said. “You don’t want to just eat guacamole all day. Of course, I have that side to me. I’m just trying to combine my love for that stuff with love for other stuff and trying to bring it all together.”

Sometimes, those upbeat songs took listeners by surprise. Reed said they shouldn’t. He noted one writer’s take on him in the ‘70s had been “very dark and foreboding. A poet that’s going to burn out quietly at 5:30 in the morning with no one there to care. A very romantic notion that bears no relationship to the truth.”

The best mix of light and dark was “Perfect Day,” which was given new life in the movie “Trainspotting,” among many other films and TV shows. It is the most bittersweet of uplifting tunes.

“It’s such a perfect day/ I’m glad I spent it with you,” he sings, sounding completely genuine and true. But then, the perfect day is touched by tension, unease as it approaches its ominous, foreboding close: “You’re gonna reap just what you sow.”

Reed said he was bipolar and he certainly wrestled with his demons — in song and in person. Various biographies — favorable ones and scabrous ones alike — have detailed the myriad of nasty fights Reed had with friends, lovers and journalists over the years, his oft-abrasive personality, the people he abruptly cut out of his circle.

In 1996 we were talking in his New York office, called Sister Ray Enterprises, and that topic of bipolarity came up. He said he tried to look at the extreme highs and lows as if they were hands on the face of a clock. The minute hand may be on 6, he said, but inevitably it will be come back to 12. It sounded simplistic, but I got it: Life’s rhythms are cyclical, not linear.

A chiseler on the rock of words

Reed and Anderson started dating in the ’90s and clearly their relationship affected his worldview. His thoughts about their relationship were woven through “Set the Twilight Reeling” his 17th solo album. Consider the impossibly infectious song called “Hookywooky.” It’s fireworks and romance, until, well, it isn’t: Suddenly, Reed is threatening to push all of her ex-boyfriends off the roof. Good old Lou.

“This is dedicated to Laurie, but not necessarily about her,” Reed said. “I have seen the theme of the album as being about change, growth and how good that is. It’s all transformation. I was actually thinking of calling it ‘Transformer Squared,’ and then I regained control of myself.”

Late in his career, as the 21st century approached, Reed stepped back and told me of the changes he’d gone through over the years.

“I think the singing is improving and the guitar playing with it, and the ability to differentiate between tones. And trying to craft a lyric. I wouldn’t want to come off as glib or trendy or secondhand, but I’m out there trying to chisel something out of that rock of words available to us,” he said. “Some of what I like is using words common to all of us and that is the challenge to me: to be able to use them so it can go directly to your heart. Hope that doesn’t sound pretentious.”

It didn’t.