Jewish prophet, trailblazer, iconoclast, inventor of the topless bikini

In Rudi Gernreich’s centenary year, a look back at a one-of-a-kind fashion phenomenon

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

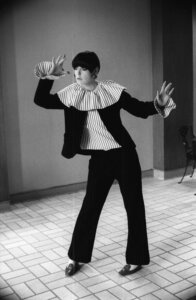

Rudi Gernreich, the Jewish Austrian-born fashion designer, who would have turned 100 this year, was more than just the inventor of a topless bathing suit. He was a conceptual artist who used clothes as a medium.

In 1964, Gernreich’s notorious so-called monokini made headlines worldwide as journalists who knew nothing about the shmatta trade recognized topless when they saw it, even if they misread the design as a sign of permissive-society raunch. Ever-analytical in the style of his landsman Sigmund Freud, Gernreich claimed to have intended an ironic reflection on body positivity and how society imposes shame and exaggerated sexual pressure on people based on what they wear.

Gernreich never intended to manufacture or sell the monokini, until urgent requests from vendors made him do so. Three-thousand of them were finally sold.

Despite its non-commercial origin, the monokini was decried by Izvestia, the USSR state propaganda newspaper, as the product of a “decadent, money-bag society,” likely an antisemitic swipe at Gernreich. The New York Herald Tribune’s Eugenia Sheppard was closer to the mark when she praised Gernreich as the “great idea boy in the business.” Style maven Simon Doonan went further, calling Gernreich “that rare fashion phenomenon: a thinker and a true prophet.”

Early recognition

The quality of Gernreich’s prophecies were recognized early. In Vienna, when he was 12, he inspired the Hungarian Jewish costume designer Ladislaus Czettel with his sketches. Czettel offered him an apprenticeship in London, but Gernreich’s mother preferred to keep him closer to home. Instead, after Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria in March 1938, the Gernreichs fled to Los Angeles.

There, Gernreich’s first job was washing corpses in the morgue of Cedars of Lebanon Hospital, founded by the Jewish businessman Kaspare Cohn. His early attempts to break into the world of clothing encountered setbacks, even as his fellow fashion-obsessed Jews recognized his talent.

In the U.S., Gernreich instructed others to pronounce his family name as rhyming with “earn quick,” but he failed to immediately fulfill that optimistic economic projection. Instead, Gernreich sold designs to Hattie Carnegie (born Henrietta Kanengeiser) a fellow Austrian Jewish emigré. He also sketched costumes for the American Jewish movie designer Edith Head (born Posener), but he intensely disliked studio strictures, even when he was working on celebrated films such as Otto Preminger’s “Exodus,” about the founding of the state of Israel.

The influence of dance

Some Jewish employers, like Morris Nagel, tried to convince Gernreich to simplify his ideas and offer more conventional looks, to no avail. Gernreich did find a kindred spirit in the Hungarian Jewish designer Renée Firestone, who had survived imprisonment in the Auschwitz concentration camp. Firestone, still thriving today at age 98, considered Gernreich’s inspirations to be essentially dance-related, and indeed he pursued terpsichorean ideals as a dancer, choreographer and costume designer with small local avant-garde troupes.

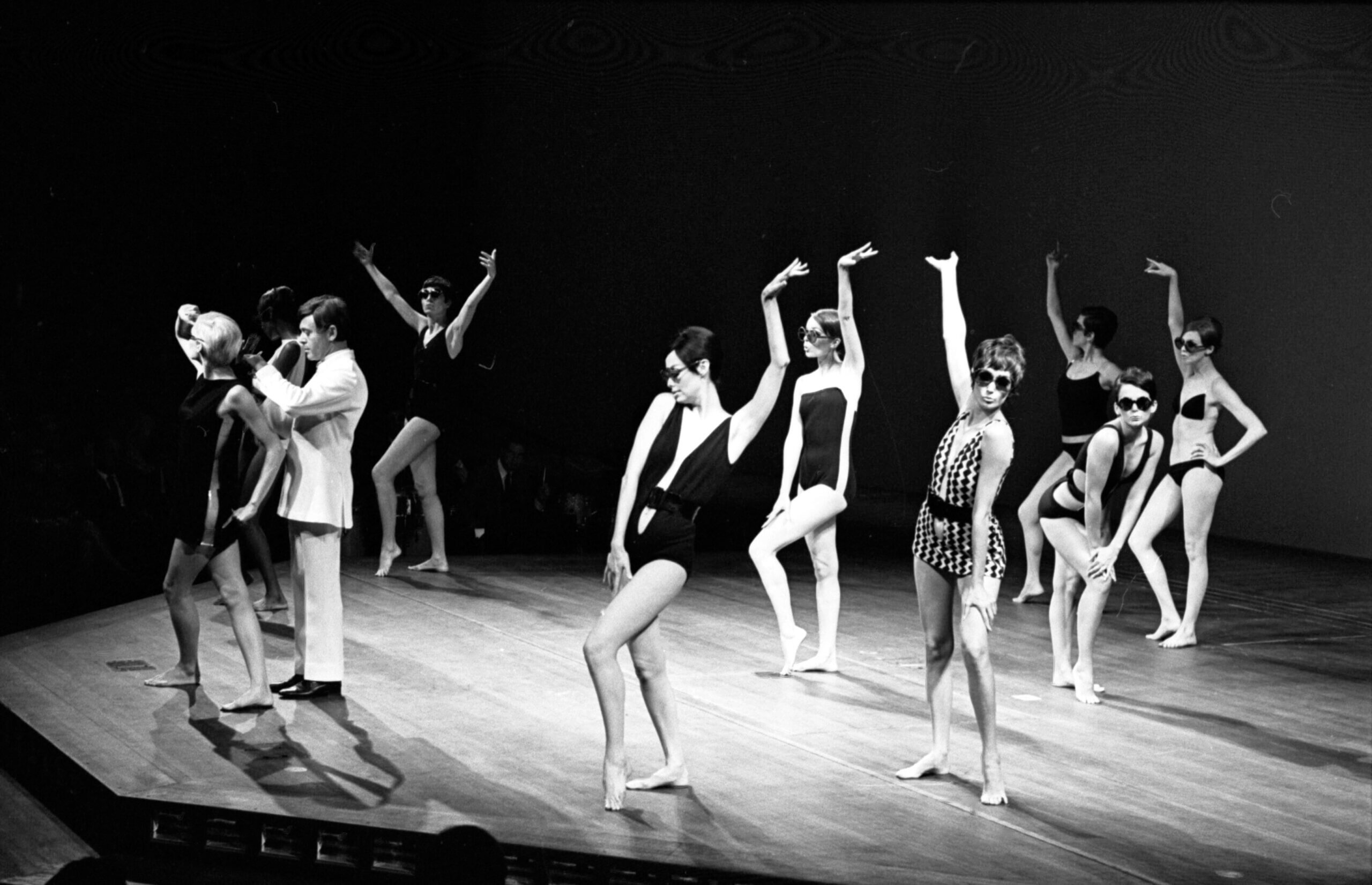

For these occasions, especially in sustained collaborations with Bella Lewitzky, a Californian of Russian Jewish origin who grew up in a utopian socialist colony in the Mojave Desert, Gernreich discovered creative personalities in tune with his own impulses. He created duotards, stretchy leotards that could be shared onstage by multiple performers, making dance into an experience of unexpected physical unity and solidarity, instead of just individual virtuosity.

A sign of his commitment to social progress was that in 1950, after meeting the activist Harry Hay, Gernreich agreed to fund the first organized U.S. efforts to promote LGBTQ rights, represented by the idealistic Mattachine Society. Gernreich cited the influence of European Jewish gay rights precursors like the sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld and film director Leontine Sagan (born Schlesinger).

Gernreich and Hay’s efforts were dramatized in “The Temperamentals,” a 2009 play by American Jewish writer Jon Marans, who told the Detroit Jewish News that he was drawn to Jewish characters. “Judaism brings a complexity to these characters that I latch on to, understand and find absolutely fascinating,” he said.

A closeted life

Part of this complexity was that Gernreich, fixated on a career in fashion, accepted that his ambitions in the America of his era would require him to lead a publicly closeted life, an option which Hay rejected. And so, like his fellow American Jews in the industry, including Chester Weinberg (1930-1985), destined to be U.S. fashion’s first prominent victim of the AIDS pandemic, for business reasons Gernreich never made any official announcement about his personal life.

Yet Gernreich was out and proud about his self-image as a man of the people. In the 1960s, he signed a contract with the chain store Montgomery Ward, which most of his haute couture colleagues sniffed at. And after the Kent State shootings in May 1970, when the National Guard killed students at Kent State University in Ohio, Gernreich responded with a holiday collection featuring mock-militaristic pieces equipped with dog tags and rifles.

Even before that, a rival Jewish designer, Norman Norell (born Levinson), who concocted elegant garb for Hollywood Jewish divas like Lauren Bacall and Dinah Shore, snootily returned his Coty Award in 1963 after Gernreich had been presented with one. Yet in December 1967, Norell reconsidered and informed Time magazine. “I take it all back,” he said, adding that Genreich was “a great designer.”

Styling Streisand

The change of attitude may have been because Gernreich expressed solid fashion concepts, not just publicity-grabbing conceptual oddities. An essential ally was the fashion-conscious Broadway star Barbra Streisand, whose first-ever fashion shoot for Vogue in 1964 was designed and styled by Gernreich. Streisand absorbed advice on how to move like a high fashion model and incorporated several poses into her onstage performance of “Funny Girl” on Broadway that same night. Subsequent Gernreich-Streisand collaborations in the pages of Vogue featured quiet elegance, with knit jumpsuits in checked purple and brown, or a dramatic green-and-black striped dress worn with go-go boots.

In 1968, when a prestigious group photo was taken for the completion of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gernreich was included as a creative spirit alongside the Jewish artists Tony Berlant and Judy Chicago and architect Frank Gehry.

Eventually, Gernreich stepped away from the fashion industry, focusing instead on housewares and formulating recipes. With a bit of Yiddishkeit, he toiled over an ideal soup based on chicken broth and served cold in whole green pepper cases, garnished with a caviar-centered lemon slice. Whether in noshes or the glamorous world of couture, on his hundredth birthday, it may be said that Rudi Gernreich fulfilled his own self-estimation to the Arizona Star in 1977: “I’ve been able to contribute to freedom — not just of the body, but of the spirit.”

His corporeal freedom did not include conquering a habit of chain-smoking his favorite Nat Sherman Cigarettellos, and he died of lung cancer in 1985 at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, an offshoot of the institution where his professional experience began in California decades before. Instead of flowers, it was suggested that donations be made to the hospice care unit at Cedars-Sinai, the proposed Bella Lewitzky Dance Gallery or the ACLU Gay and Lesbian Chapter.