Guitar hero, defender of Dylan, leftist, Trumpist, a good friend and his own worst enemy — Danny Kalb was one of a kind

At one point, the fleet-fingered musician was touted as leader of the Jewish Beatles. Then, he fell off the map.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

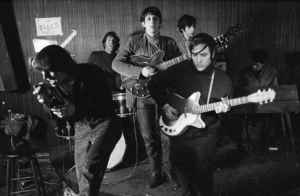

If you were into the New York folk music scene in the ’60s, you know how important and influential the blues-rock group The Blues Project was. Created in 1964 by its lead guitarist Danny Kalb, its famous gigs at the Café Au Go-Go in Greenwich Village in Manhattan attracted a large and enthusiastic audience, mesmerized by their blending of traditional folk blues, electric blues, and new folk-rock versions of acoustic songs like Donovan’s “Catch the Wind” and Eric Andersen’s “Violets of Dawn.”

Danny was one of my oldest and closest friends. I met him when he was in high school and I was at the University of Wisconsin-Madison; he later joined me there. When we both had returned to New York our friendship continued and deepened over the decades. After a long and hard three-year illness fighting cancer, Danny died at the age of 80 in a Brooklyn hospice home on the afternoon of Nov. 19.

There are numerous places one can read of his musical accomplishments, especially those with The Blues Project, and the scores of records and CDs he made. There’s the workmanlike and thorough obituary by The New York Times’ rock critic Jon Pareles. Ultimateclassicrock.com features links to his music and the major rock site, bestclassicbands.com rightfully notes that Danny was one of the first American “guitar-heroes” whose “lead lines, whether high-velocity and stinging or slow and measured, were never less than dazzling, and always packed with emotion; he never sacrificed tastefulness for flash.”

Danny said his life changed when he attended a concert by the great John Lee Hooker. He had musical aspirations, but he was a Westchester suburban New York Jewish kid, whose life revolved around high school friends and a weekly “Marxist study group.” His parents were members of the Old Left communist crowd, and he rightfully called himself “a bona fide Red Diaper Baby.” Thus Danny came into his new musical orbit as a rigid, familiar kind of old leftist — a man who knew he was on the right side of history and that his country wasn’t. As he put it in a quip at a concert, “I’m just a suburban Stalinist.”

Indeed, I first met Danny at a New York City downtown SANE Nuclear Policy rally chaired by the patriarch of social democracy, the six-time Socialist Party presidential candidate Norman Thomas. As Thomas spoke from the sound truck stage, he saw a group of young people with signs arriving at the event. They were led by Danny, who headed the Westchester peaceniks who had marched all the way into the city from the suburbs. Thomas called him up on stage to let the crowd hear what motivated them to attend. I knew his cousin and others in the group. I was introduced to him and made a connection that would quickly evolve into a friendship.

Already in this leftist cultural milieu, Danny soon discovered the Village and Washington Square Park, where every Sunday afternoon, folksingers, bluegrass pickers and blues devotees met to jam. These “protestor-mavens and long-haired young girls,” he wrote in Fretboards magazine back in 2015, proved to him that “some powerful change was a-borning.” There, he met and became influenced by the blind Reverend Gary Davis. It was “like hearing God himself, if God was a blind street singer playing for tips,” he quipped. Davis’s “If I Had My Way” became Danny’s signature song, and he usually concluded his shows with it.

To learn blues technique, Danny first turned for lessons to the one guitar player from the Old Left scene who could play the blues, Jerry Silverman. He knew the fundamentals, but unlike Danny, Silverman had no passion or soul. He performed regularly at People’s Artists hootenannys in the ’50s, but outside of these small circles in left-wing New York City, his impact came not from performing, but in the over 200 books he wrote on music and guitar.

At the Square, Danny met Dave Van Ronk, who helped to move him away from his parents’ leftist traditions. He described Van Ronk as an “anarcho-syndicalist wise in the ways of the outré left.” Before long, Danny developed his own style, which, he wrote, “drew on the folk music I played with guys like Dylan, Phil Ochs and Dave Van Ronk, the acoustic blues of Gary Davis, the electric blues of Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf and the rock ’n’ roll of Chuck Berry.” Years later, Danny and the Blues Project would be Berry’s backup band for a New York City gig. This all led in ’65 to the formation of The Blues Project.

Before he created the group, Danny played and sang everywhere for small bits of change. One of his regular gigs was with a duo they called Marshall and Dan — that would be Danny and Marshall Brickman, later of The New Journeymen and the Tarriers. Marshall is now better known as a screenwriter, director and author of the Broadway hit Jersey Boys.

“I was honored to be one half of the act revered throughout the Jewish mountains as ‘Marshall and Dan,’ dinner entertainment providing background music as our fans crammed dinner rolls into their pocketbooks,” Marshall emailed me after Danny passed. “You may smile, but remember: no contribution is too small.”

Danny and The Blues Project revealed how many NYC Jewish kids were drawn to this new music, which brought a rock ’n’ roll sensibility to folk music. For a short time, many thought The Blues Project would become the American equivalent of The Rolling Stones, especially since their one non-Jewish member, Tommy Flanders, was compared in his style and his power to Mick Jagger. Flanders, in a self-defeating move, suddenly quit the group literally before they were going on stage for a major music industry showcase, leaving them with no vocalist. The dream of their becoming “the Jewish Beatles” (as they were dubbed by many at the time) was not to be, although at first, like the Beatles, their original producer was Sid Bernstein.

The Blues Project’s influence spread far and wide. The effect that The Blues Project had on the future Jewish intellectual and author Leon Wieseltier in what he calls “deepest darkest Brooklyn” was profound.

“Nothing,” Wieseltier wrote me, “made an aspiringly hip young man at a yeshiva high school feel hipper than The Blues Project. Kalb, Katz, Kooper, Blumenfield: It seemed also like the Jews Project. (What was Tommy Flanders doing there?)” It was “decades later,” he notes, “I regaled Danny, who had become a cherished friend, and Al, who had become a cherished acquaintance, with these stories of my happy provincial youth, and we laughed, but my gratitude was lifelong and deep.”

Danny’s guitar playing inspired other musicians As New York Times music critic Jon Pareles writes in his obit, “his wiry, keening lead guitar lines infused the band’s arrangements with a hectic intensity.” Pareles quotes guitarist, record producer and leader of The Patti Smith Band Lenny Kaye as saying that Kalb was one of his very first guitar-heroes, “his fleet fingers bridging acoustic folk as it metamorphosized into electricity.”

Then, suddenly, it appeared that Danny dropped out of the scene. “What ever happened to Danny Kalb?” a fan once wrote to the letters page in Rolling Stone, a query that went unanswered. The truth was that after taking a “bad acid” trip in San Francisco, his descent to hell came quickly. Danny had had emotional problems before and the LSD accelerated a deep negativity, a quick decline, and many episodes of him becoming his own worst enemy. Sadly, I don’t think there are any of his friends — and I include myself — whom he did not viciously turn against, considering them to be enemies out to hurt him. There are two I know, both of whom were musical partners as well as friends, who never spoke to him again after he attacked their character.

Sadly, Danny revealed a regular self-defeating streak that prevented him from achieving the success he craved and which most fans assumed he would reach. There were scores of gigs canceled at the last moment, without good reason. One of Danny’s great fans was John Belushi, who showed up regularly at their NYC gigs. When he and Dan Ackroyd formed The Blues Brothers, he asked Danny to be lead guitarist. Danny came to the very first rehearsal, where the two leads handed out the uniforms the band members would wear. Danny stormed out, saying he would not desecrate the Black blues in such a fashion. When Danny came to his senses a short time later and said he would join, it was too late — they had already hired Steve Cropper and Donald “Duck” Dunn to take the parts that Danny was meant to have.

During a short break at a recording session in which he was accompanying the famous Chicago folk duo Hamilton Camp and Bob Gibson, Danny suddenly threw himself out of the window from the third floor, hoping that would put an end to his misery. God, as he would later put it, must have been with him, because he came out with no physical scars, but mentally unable to function. He landed first on a canopy which broke his fall. From there, it was straight to a year or two rehab in a facility for those with severe psychological problems.

His politics took a sudden turn. A man of the solid left, Danny drifted more and more in a rather unexpected direction. In recent years, he would phone and regularly hector me about my failure to comprehend America, sounding like a repeat of the previous night’s prime-time lineup on Fox News. When I sought to argue with him, he would reply that people like me were “simply professors or self-proclaimed intellectuals, while I am a musician who gets the real America.”

And God forbid if one would say anything critical of his hero and old friend, Bob Dylan. When Dylan arrived by bus from Minnesota to Madison, Wisconsin, in January 1961, Bobby phoned me from the bus station asking if I could put him up. Since I didn’t have any room, I got in touch with Danny who willingly set him up on a spare couch. From that moment on, Dylan became his hero and his role model, as well as a fellow folkie and blues enthusiast. Dylan, he said to me many decades later, was “brought to us by God as his Prophet,” and Danny was not kidding. My wife once made the mistake of telling him she didn’t like Dylan’s Christmas album, which led to a blow-up and a temporary halt in friendship that lasted a few years.

Danny’s problem was that he countenanced no disagreement. I admonished him many times and suggested that he had to understand that some people saw things differently, and he could challenge them with words but that anger would do little. He said he could not stay friends with people whose outlook he abhorred, and added that if I did not take him seriously and eventually agree with one or another tirade, he would not be able to talk to me anymore.

After weeks or sometimes months, and even a year or more, he would call and tell me that friendship transcended deep political differences. How sad that near the end, he seemed to have forgotten that lesson. When we talked the past six years, he would lecture me about why Trumpism was the right turn for America’s future.

Some of Danny’s friends stopped taking his phone calls. But one had to look past his quirks and problems to see how he revealed his soul in his music. He was, as historian and musicologist Sean Wilentz wrote me, “always at heart the tenderest of souls. Long after he touched with his music, he touched with that tenderness.” Mark Ambrosino, Danny’s producer and drummer for his band at Sojourn Records, said that his playing and singing was “powerful, soulful and honest.” He could move from playing something intimate that “would bring you to tears, and then erupt into what felt like the jagged edge of broken glass that would cut right through you.”

As news of Danny’s death spread, more and more tributes and remembrances began to pour out, including one in an unexpected venue, National Review, written by editor and writer Richard Brookhiser. In past years, he too stopped taking Danny’s phone calls, thus he thought that Danny still considered him a leftist who, as Brookhiser writes, was still “trying to integrate radicalism somehow with patriotism.”

So long, old friend, may your final resting place give you the peace and calm you sought, as you will see from above how new generations will find and come to love your music and your contribution.