Is saying that Jews are wealthy and powerful really a compliment?

Kanye West and others argue that conspiracy theories about Jews can’t be antisemitic — they’re too nice

Rich Jews — er, rich in chocolate gelt. Photo by iStock

You know that old joke. A Jew is reading a Nazi newspaper. His friend asks him why and he says something like, “When I read the normal newspaper, it’s all doom and gloom and antisemitism. But when I read the Nazi paper, we Jews are doing really well! We own Hollywood, we control the media and we are all rich doctors, lawyers and bankers.”

Of course, these are antisemitic conspiracies — that’s the joke. But there’s a seed of truth there: Jewish stereotypes can sound oddly complimentary.

Even Kanye West — who legally changed his name to Ye — can sound philosemitic at times. On Tucker Carlson’s show, the rapper said he wished his kids learned about Hanukkah instead of Kwanzaa at school — so that they could learn “financial engineering.” And in 2015, after talking about conspiracies regarding Jewish information sharing, Jewish control and Jewish wealth, he denied any antisemitism. “That’s a compliment,” West said. “I love Jews.”

He’s not the only one. Some people online have attempted to defend West by saying that his antisemitic comments about Jews are really compliments. And other politicians, including Trump and Michele Reynolds, have made comments about Jewish business or financial prowess, which they also retroactively excused as well-intentioned appreciation.

Other groups’ stereotypes are obviously defamatory. So how did Jewish stereotypes become so different? And are they as harmful as open insults?

‘Poisonous power’

There are plenty of negative stereotypes about Jews: That Jews are untrustworthy, weak, greedy, ugly. There are the weird ones, like blood libel, about Jews drinking Christian children’s blood.

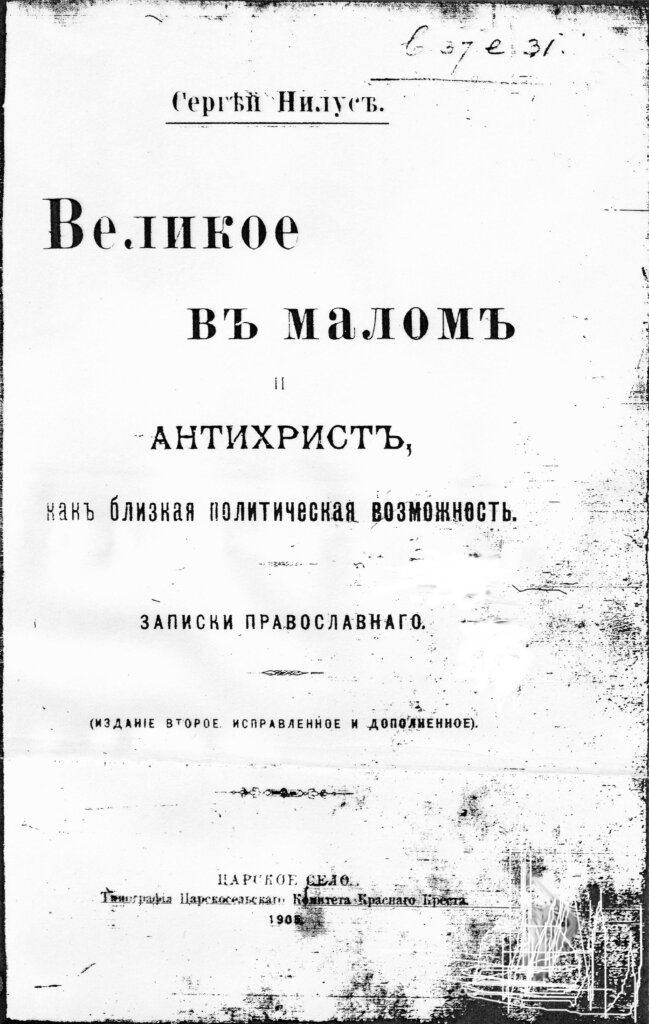

But a tractate called Protocols of the Elders of Zion published first in Russia in 1903, marked a change in prevailing ideas about Jews. Purportedly written by a council of Jewish leaders, it outlined a plan for Jewish global domination.

“The Protocols are, in my view, the essence of antisemitism, which is the idea of Jewish poisonous power,” Kenneth Jacobson, the deputy director for the Anti-Defamation League, told me. “For the antisemite, the Jew is not what he or she appears to be. The reality of the Jew is something hidden, something more powerful.”

This allows antisemitic conspiracies to sidestep the need for any evidence — the lack of it is simply proof of the insidious nature of Jewish skill subterfuge.

“The idea that Jews, particularly Jews in Russia, who had no power whatsoever, were coming together to take over the world, is the most preposterous thing, and yet it resonated so tremendously,” said Jacobson.

The Protocols were not the first instance of a conspiracy about Jewish domination and power. Still, the Protocols had a lasting effect, one which Jacobson attributes to the era in which it was published. In the early 20th century, urbanization was creating a massive shift in people’s lives, identity and economic status, provoking an atmosphere of anxiety.

“When people are living in a state of anxiety for a variety of political, social, economic reasons, it’s been said a million times in the past, they’re looking for a scapegoat. More than a scapegoat, they’re looking for an explanation to themselves,” said Jacobson. “Jewish power is the number one conspiracy about that.”

Even after the London Times debunked the Protocols in 1921, showing it to be a forgery, it was translated into numerous languages and spread around the world. And whether or not antisemites cite it — or have even heard of it — it indirectly influences their ideas.

A threat to white society

Most racist stereotypes focus on putting down another group, positioning them as lesser, undesirable or worthless. And while some Jewish stereotypes do this — think about caricatures of Jews as nebbishy, nerdy or weak, hook-nosed and beady-eyed — stereotypes of Jewish power function differently.

Contrasting Jewish stereotypes with those of other groups makes them seem less harmful. But stereotypes about Jewish wealth or control position Jews as a worthy adversary for white supremacists or antisemites, a group to be feared and defeated, not simply ignored or excluded.

On Instagram, Jamyle K. Cannon, the founder of Chicago nonprofit The Bloc, said he had been talking to a Black man in his 20s who had said talking about Jewish wealth and power was a compliment — how could it be antisemitic?

Cannon, who is Black, said stereotypes about Black people, “paint the picture of a group of people who are a drain on society unless they are broken, controlled, imprisoned, or enslaved.”

But stereotypes about Jews conjure “a picture of a group of people who can compete with, outperform and even subjugate white people in the open market,” he said.

“Goebbels in Germany was all about this,” Jacobson told me. “He basically convinced the German people not to merely dislike Jews, but that you have to fear Jews — and you have to defend yourself against these Jews.”

And these ideas about Jewish control mesh well with stereotypes and conspiracies about other minorities. The “great replacement theory,” a longtime white supremacist conspiracy promoted by conservative ideologues including Tucker Carlson and the Tree of Life shooter in Pittsburgh, posits that minorities are attempting to take over the world and exterminate white society and culture.

But given that stereotypes about most ethnic minorities portray them as stupid or weak, some other group must be masterminding it, puppeteering the people of color — the Jews, of course.

Conspiracy goes mainstream

Conspiracies about Jewish wealth, power or control have roots in medieval Jewish money lenders, in the Christian Bible, in the Protocols, in Nazi propaganda. And people in the corners of the internet where hate speech and conspiracies brew, on sites like Gab or 4chan, continue to propagate them too.

But with public figures such as West making unambiguously antisemitic comments, or Trump meeting with virulent antisemite Nick Fuentes, the ideas are being mainstreamed.

Jacobson said the ADL has not seen evidence that public figures such as West, Trump or Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene openly promoting antisemitic ideas has swayed greater numbers of people against Jews. In the ADL’s recent surveys, Americans’ attitudes toward antisemitism have stayed relatively stable, with between 11% and 14% of Americans holding antisemitic ideas.

The issue, he said, is not numerical increase, but mainstreaming antisemitic ideas. If even under 15% of Americans hold antisemitic ideas, that means around 30 million people are walking around hating or feeling threatened by Jews. They just never felt emboldened to act on those ideas.

“I don’t think the American people are more antisemitic, but those people who are, are getting too much support,” said Jacobson. “There’s plenty to worry about.”