Why we should think twice before we call Hitler a ‘demon’

President Biden recently labeled Hitler ‘demonic,’ but Yiddish linguists say he could have chosen a better word

A carnival parade float of Hitler in Dusseldorf, Germany, 2007. Photo by Getty Images

What’s wrong with praising Hitler?

That’s a question most of us never expected to have to answer, and a question I never expected I would type. But when a former American president publicly dined with Holocaust deniers and Hitler aficionados, the current president of the United States chose to try and answer that question.

“Hitler is a demonic figure,” Joe Biden tweeted, after making it clear that yes — the Holocaust happened.

The word “demonic” felt a bit off to some scholars and translators.

“It doesn’t make me uneasy; but it doesn’t feel right, either,” said Larry Rosenwald, professor emeritus at Wellesley College, and an active Yiddishist. “Calling people demonic means classifying them as non-human, which implies that human beings are incapable of the things Hitler yemach sh’mo (‘may his name be blotted out’) or others have committed. And of course human beings are not at all incapable of them.”

Rosenwald likened the phrase to saying “this is not what America is” when, he added, “it’s exactly what America is, with its traditions of lynching and expulsion.”

“Demons are demons, people are people. When Bashevis writes about demons,” said Rosenwald, referencing the work of Isaac Bashevis Singer, “they’re a different species; they insinuate themselves into mirrors to entrap self-indulgent women.”

‘The corrosion of political discourse’

But first things first — word choice aside, and however “demon” may sound to all the good souls who are reading I.B. Singer, it’s a very good thing to have a president who is anti-Hitler. You would think that would be a basic requirement of every American politician, but these days, it is not.

As the PBS NewsHour soberly detailed, its correspondents called every Republican senator and five other prominent Republicans, and only a few would condemn Trump’s choice to host a dinner at Mar-a-Lago with known neo-Nazi, Holocaust denier and white supremacist Nick Fuentes, and Ye, the musician formerly known as Kanye West, who has made his antisemitic views and admiration of Hitler very public.

“It’s reprehensible. If a Republican is in leadership, they should have been out there within hours of finding out about this dinner,” Washington Post columnist Jonathan Capehart said on the NewsHour. “This is what’s leading to the corrosion of political discourse. And, in our society, we have people who are openly, openly antisemitic, and no consequences. That’s outrageous.”

Capehart’s comments were made on Shabbat, so many observant Jews missed them; I was grateful to have heard them after Shabbat ended.

Let’s not take a prominent columnist’s decency, or a president’s decency, for granted, especially with the memory of “very fine people on both sides” still fresh in our minds. Biden has said that the Charlottesville march of torch-bearing men, which included the yelling “Jews will not replace us,” is what motivated him to run for president. And Biden, who has repeatedly said that his concern is for the soul of America, is absolutely right to explicitly call out the “silence” of prominent people who refuse to say that Hitler was a mass murderer.

But let’s get back to demons.

‘It’s more likely to see Hitler associated with Haman’

It’s interesting to note that in Yiddish, the mother tongue of many victims of the Holocaust, a demon may not exactly be what a demon is in English.

“Sheyd — ghost or demon or spirit or ‘mazik‘ evildoer — does not necessarily imply evil, though it can be a trickster figure, responsible for temptation — or it could possess a human body and cause confusion, distress and physical ailments,” said Jessica Kirzane, editor-in-chief of In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies, and a professor of Yiddish at The University of Chicago.

“Tayvl — linguistically related to the English word devil — does have more of this kind of association. And you can say ‘tsum tayvl’ — ‘go to the devil’ — to mean an equivalent of ‘go to hell,’ but I would still not associate the word with Hitler,” Kirzane said.

Staying with the devil theme for a moment, “there are some associations between evil and especially tayvl, and European/Christian literatures about devils generally are translated into this world, creating further associations with a more Christian conception of good and evil,” Kirzane said.

“Still,” she added, “it seems more likely to see Hitler associated with Haman, or with Amalek — that is to say, evil human actors.”

‘I was not acquainted with hell’

Whether Hitler is portrayed as Haman or a demon or anyone else, scholars noted that using any metaphor when discussing the Holocaust can be tricky.

“Why are metaphors tricky? Imre Kertész explained the issue brilliantly in his Holocaust novel Fatelessness,” said Samuel Spinner, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins and the author of Jewish Primitivism. “The novel is, to a degree, entirely about the question of the role of metaphor in communicating the experience and history of the Holocaust. The last few pages are directly about it.

“The novel’s protagonist, newly arrived home in Budapest after surviving Auschwitz, meets a journalist who wants to hear from him about ‘the hell of the camps,’” Spinner continued. “Kertész narrates his protagonist’s thoughts in response: ‘I had nothing at all to say about that as I was not acquainted with hell and couldn’t even imagine what that was like.’”

Spinner said he found himself thinking of Kertész’s concern with “how to narrate the Holocaust without rhetorical inflation” while reading the online discussion on Biden’s language.

“Some of the replies I saw on Twitter said that ‘demonic’ — and by extension any metaphor — just means what it means,” Spinner said. “Kertész deals with this objection too, writing that the journalist assured the protagonist that ‘it was just a manner of speaking.'”

The journalist in Kertész’s story then asks: “Can we imagine a concentration camp as anything but a hell?” The protagonist replies that “everyone could think what they liked about it, but as far as I was concerned I could only imagine a concentration camp, since I was somewhat acquainted with what that was, but not hell.”

‘This subtly diminishes the personal responsibility’

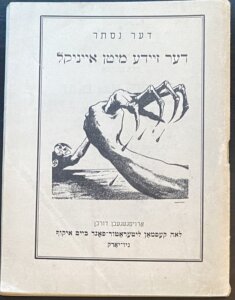

Spinner pointed out that an image of Hitler as a kind of demon appeared on the cover of a story by the famed Yiddish writer Der Nister, published in New York in 1943.

Interestingly, in the past, Jewish publications have used “demon” to describe Hitler. A February 1954 Commentary headline read: “The wretched little demon that was Hitler: What Possessed the Soul of the Third Reich.”

In 1987, The New York Times ran a letter to the editor with the headline “Hitler and the Demonic,” in response to a William Safire column. The letter writer, Gail Horsman Rivera of Brooklyn, did not like the supernatural framing of Hitler that she felt Safire employed. Like today’s scholars commenting on Biden’s use of “demonic,” Rivera felt this framing placed Hitler outside of the realm of human nature.

Safire’s article on a joint communiqué issued by Roman Catholic and Jewish leaders “contained some astute observations,” Rivera wrote. “However, I am not as pleased as he to see the word ‘demonic’ used to describe Nazi ideology. This subtly diminishes the personal responsibility of Hitler and his followers in formulating and perpetrating their crimes. It implies that their deeds were supernaturally evil. They were extraordinarily evil, but the history of our planet has shown again and again that this kind of depravity is well within the bounds of human nature. It is all too easily repeated without any help from supernature.”

Some scholars have said that describing Hitler as a demon removes the spotlight of guilt from his millions of followers — without whom the Holocaust would not have happened.

In “Man, Demon, Icon: Hitler’s Image between Cinematic Representation and Historical Reality,” scholar Michael Elm writes: “Although historians have emphasized Hitler’s decisive role in the Holocaust, it is nevertheless somewhat misleading to portray him as a demon.

“Indeed, although Hitler himself was unquestionably wicked, the bureaucratic organization and efficient implementation of the Final Solution cannot be perceived as the act of a single person. Viewing it as such risks overlooking the role played by the many knowledgeable German citizens who actively assisted with or took advantage of the deportations and murder.”

‘The same demon that lived in Babylon’

When I heard the word “demonic,” I immediately thought of the extreme Biblical commentaries I have encountered which explain too much through the idea that a demon, or alternately, Satan, is behind everything.

Consider this RealFaith.com commentary on Daniel 3:8-15 by Pastor Mark Driscoll titled “Same Demon, Different Hitler”:

“When you see the exact same evil thing happening at various points in history, often it is because the same demonic spirit is at work behind the scenes,” Driscoll writes. “Some things never change. The same demon that lived in Babylon with Nebuchadnezzar later moved to Germany with Hitler.”

This idea that Nazi horrors can be explained by a “demon” who flies through the centuries is, I think, part of what made scholars queasy when they read Biden’s tweet. But I doubt that the RealFaith.com perspective is what Biden drew on; instead, I think he leaned on something far more personal — his own father’s view of the Holocaust.

The anger of Joe Biden’s father

In 2015, I heard Joe Biden speak at the Reform Jewish Biennial in Florida. He was on a goodbye tour, and he thanked the Reform Jewish community for its support of gay marriage, when it was the only religious group that did so. He said he was sure that the Reform movement’s support for trans rights would also come to be viewed as the just thing to do.

The main part of his speech was about his father’s horror, expressed at the dinner table, over the mass murder of the Holocaust, and how, in memory of his father, he took each of his children on a father-child trip to Dachau when they became teenagers.

I cried as I listened to Biden describe taking his teenage daughter to Dachau and talking about how that trip alone with their father had changed each one of his children. As I read online discussion swirling about “demonic,” I thought of how this is a president who takes his children to a concentration camp to honor his father’s memory and moral vision.

I could hear Biden’s father’s anger in “demonic.”

What is potentially “demonic” is the continued willingness of some American voters to believe in lies — and anoint leaders who anoint lies. I hear the fear of that willingness in Biden’s word choice, too.