In this overlooked documentary, the son of Holocaust survivors embarks on a seemingly impossible mission

In ‘The Presence of Their Absence,’ Fred Zaidman searches for evidence of his family’s lost story

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Donna Kanter’s documentary, The Presence of Their Absence, was released in 2019 but for whatever reasons slipped below the radar. That’s unfortunate. It’s an intriguing peek into the world of a contemporary American Jew obsessed with his ancestry, which was lost in the Holocaust — its presence on earth obliterated, archival records destroyed. Fred Zaidman, the son of Holocaust survivors, was determined to restore his forebears’ identities and by so doing, loudly proclaim that they lived and mattered.

Zaidman knew virtually nothing about his lineage. The Los Angeles native grew up in a world of mostly suppressed sorrow. “My parents were protecting me or themselves or both,” he says.

In his 60s, and in the wake of his parents’ deaths, he embarked on a quest to discover what had happened to his family during the Shoah with one primary goal — to find a single photo of his grandparents. His journey took him to Poland, Israel and finally to Atlanta. He met cousins he never knew he had and received help from Steven D. Reece, an Atlanta-based Baptist minister who established The Matzevah Foundation, a nonprofit corporation committed to rehabilitating and preserving Jewish cemeteries in Poland as an act of reconciliation.

Kanter’s camera unobtrusively followed Zaidman as he uncovered his roots, constructed a family tree and restored the gravesites of his ancestors and others. Kanter is best known for her lively 2012 film, Lunch, which features her father, comedy writer Hal Kanter, along with 11 comedy icons of yesteryear, including Sid Caesar, Monty Hall and Arthur Hiller, who gathered for a weekly midday meal to exchange thoughts, affectionate barbs and witticisms.

The Presence of Their Absence is far removed from the world of midcentury comics. But always interested in the children of Holocaust survivors, Kanter thought that this narrative begged to be told.

Who is Fred Zaidman?

Zaidman emerges as an ambiguous character, which adds an interesting layer. We don’t know, for example, if he was married or has had children. Likewise, it’s not entirely clear what he did for a living or if he is fully retired. He says he started working when he was 12, competed in sports and at some point ran businesses, though it’s not clear what they were. Today he spends much of his time engaged in charitable efforts such as volunteering at a food pantry, shooting hoops with underserved youngsters, and donating blood. Indeed, he claims to have donated 273 times, reportedly a world record. He credits his mother and father with instilling in him a sense of compassion and a need to help the less fortunate. Towards the end of their lives he was their caregiver.

Still, he confesses to a lifelong feeling of disconnection. Raised among Polish- and Yiddish-speaking families, he wasn’t certain if he belonged in the “old” or “new” world. The invisible wall that separated his past from his present was yet another source of existential detachment.

The need to track down his origins became all the more urgent in the wake of his parents’ death. He was now their emissary on earth, attempting to answer their unvoiced questions. Zaidman’s brother suggests it was Fred’s expression of grief and his way to maintain a bond with his now deceased parents. A childhood friend says he was looking for the love that his unknown grandparents embodied — “They were the angels in his life.”

Visiting Poland

Whatever his motivations, he comes through as a brave man. He had no way of anticipating whether his expedition would prove fruitful at all, or how he would be perceived, or even the emotions that he might experience. Suffice it to say a range of feelings were aroused — rage, overwhelming sadness, joy. Visiting the sites where his parents’ homes once stood in Bedzin and Dabrowa-Gornicza, he found instead a parking lot and a barren stretch of land. He desecrates one area doorway with a key, etching the year “1939” onto its surface and spitting.

In several ancient untended Jewish cemeteries, Zaidman finds busted headstones, gravesites overgrown with weeds, profanities and swastikas scrawled across the granite outcroppings. He reports the vandalism to the gatekeeper and later the police. He makes his own repairs, pulling together a small broken tombstone, its severed pieces now somewhat aligned on the ground, and uttering a prayer for the unknown dead.

Planning the trip was labor-intensive and time-consuming. Zaidman immersed himself in Ancestry.com, wrote letters, conducted interviews and finally ferreted out experts who would meet with him in Poland, including archivists, historians and genealogists from such places as the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute and the Institute of National Remembrance.

The information he sought — who made up his family; where did they live; what happened to them — was nearly impossible to ascertain. The authorities told him people may have lived in one place but were registered elsewhere. The idea of finding photographs seemed even less likely. They were rarely attached to documents other than passports and university applications. Those he speaks with are courteous and compassionate, but a few seem puzzled by his steadfast commitment to find tangible locales, pictures and gravesites.

A turning point comes when Zaidman meets historian Adam Szydłowski who brings him to a most improbable Polish restaurant, Cafe Jerusalem, which offers kosher food and serves as a gathering place for diners to view archival documents and objects from prewar Jewish Bedzin. Szydlowski, one of the two non-Jewish heroes in this story, was the restaurant’s manager and a major player in its creation. It opened in 2015 and marked the return of the first Jewish business in the region in more than 75 years.

Attending a Shabbat dinner at the café, Zaidman said, was one of the most moving experiences of his life. His grandmother was no longer the ghost of a stranger. Her presence in that room in that moment was palpable. “She was there,” he said.

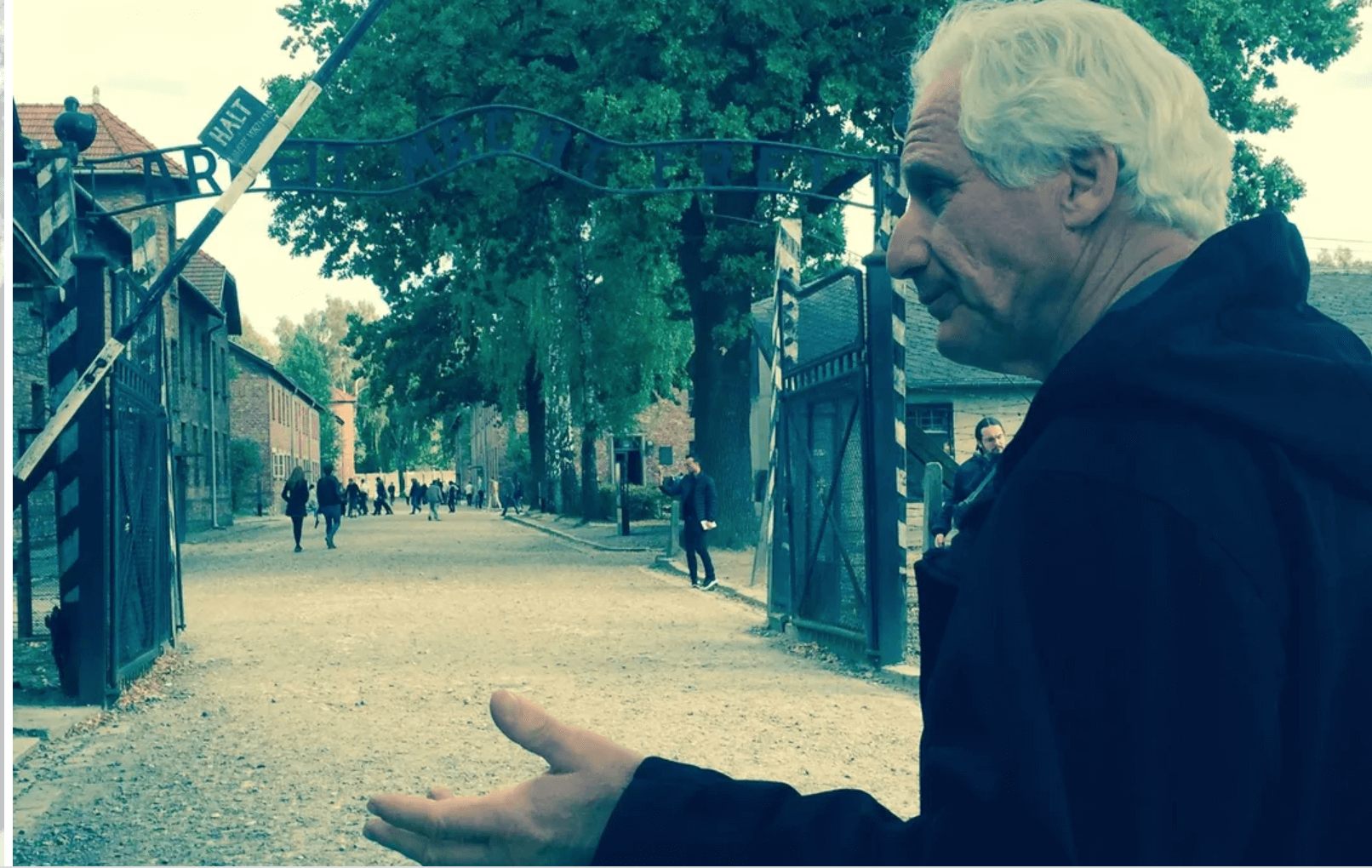

At Auschwitz

No place, however, resonates more forcefully than Auschwitz-Birkenau, where his grandparents were killed in the gas chambers. He knew well how the Nazis divvied up the newly arrived Jews into two lines, one line of prisoners headed for the “showers,” while the shorter line queued up with the more fortunate Jews tapped for slave labor.

Zaidman’s grandparents were destined for death, while Zaidman’s mother, a young girl at the time, was herded to the other line. She refused to release her parents’ hands until she was forced to do so. That familiar story and, especially, the flesh and blood personhood of his grandparents, had no reality for Zaidman until he was standing in the camp, perhaps on the very spot where it happened, staring out at the silent flat land still flanked by barbed wire.

“Being here makes it real,” he says. “This is the closest I will ever be to my grandparents. If I could I would stay here a very, very long time.”

In Yad Vashem, with the help of seasoned researchers, he is able to unearth more detailed family history. He views a photograph of an uncle, and learns the death date of his paternal grandmother, June 1, 1943.

“I can now light a Yahrzeit candle for her,” says said.

He is introduced to engaging and accomplished Israeli cousins whom he did not know existed and later has an intense reunion with a second cousin, a 60-ish attorney in Atlanta, who was previously a stranger too. They compare upbringings, study old family albums, noting physical resemblances between this one and that, and speculating about the fate of others they had never met. They sob with the realization that their meeting is in and of itself their triumph over Hitler.

For me, the most fascinating and admirable figures in this film are the non-Jewish archivists, genealogists and especially Szydłowski, the historian, and Reece, the Baptist minister and his many non-Jewish minions who care for and restore Jewish cemeteries in addition to commemorating mass grave sites in Poland. They are extraordinary.

At the Radomsko Cemetery, Zaidman works alongside Reece and his followers in clearing the burial ground, manually digging out the weeds and patting down the earth.

“Working in the dirt with one’s hands is very intimate,” says Reece, who, while plowing through the brush and searching everywhere, finally pinpoints the gravesites of Zaidman’s two great-grandfathers, one great-grandmother, and one great-aunt. Their disclosure is a stunner. And the silent collaboration between Jew and non-Jew at the cemetery is visually and emotionally compelling. It’s to Kanter’s credit that she allows the image to speak for itself.

At the end, Zaidman returns to Bedzin’s Cafe Jerusalem to offer the restaurant a photograph of his parents on their wedding day, which took place in Bergen-Belsen’s Displaced Persons Camp, very far from home. Nailing the framed picture onto the wall, Zaidman has brought them home.

Though he has never found a photograph of his grandparents, Zaidman has not given up hope and will continue to look. Still, some of his questions have been answered and he seems more comfortable in his own skin and accepting of himself in the world. The larger questions remain unanswerable.

The Presence of Their Absence is available on Amazon, Vimeo, itunes, and youtube, among other platforms.