Why is this Jewish artist’s murder confession being hidden again?

A new film faithfully brings Charlotte Salomon’s magnum opus to screen, yet excises an essential part

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

For years after Charlotte Salomon died at age 26 in Auschwitz, her father Albert and stepmother Paula only showed the manuscript she left behind to one person: Otto Frank. He, too, had shown the Salomons his daughter Anne’s diary to ask if they thought it was worth publishing.

In the end, of course, Frank published Anne’s diary — with some edits, for privacy and propriety — and it became a sensation. Anne became the image of the Holocaust victim, angelic and martyr-like.

Charlotte’s parents published her manuscript too — also editing out the most controversial part — but it’s hard to imagine anyone less likely than Charlotte to be turned into a similarly angelic, appealing heroine.

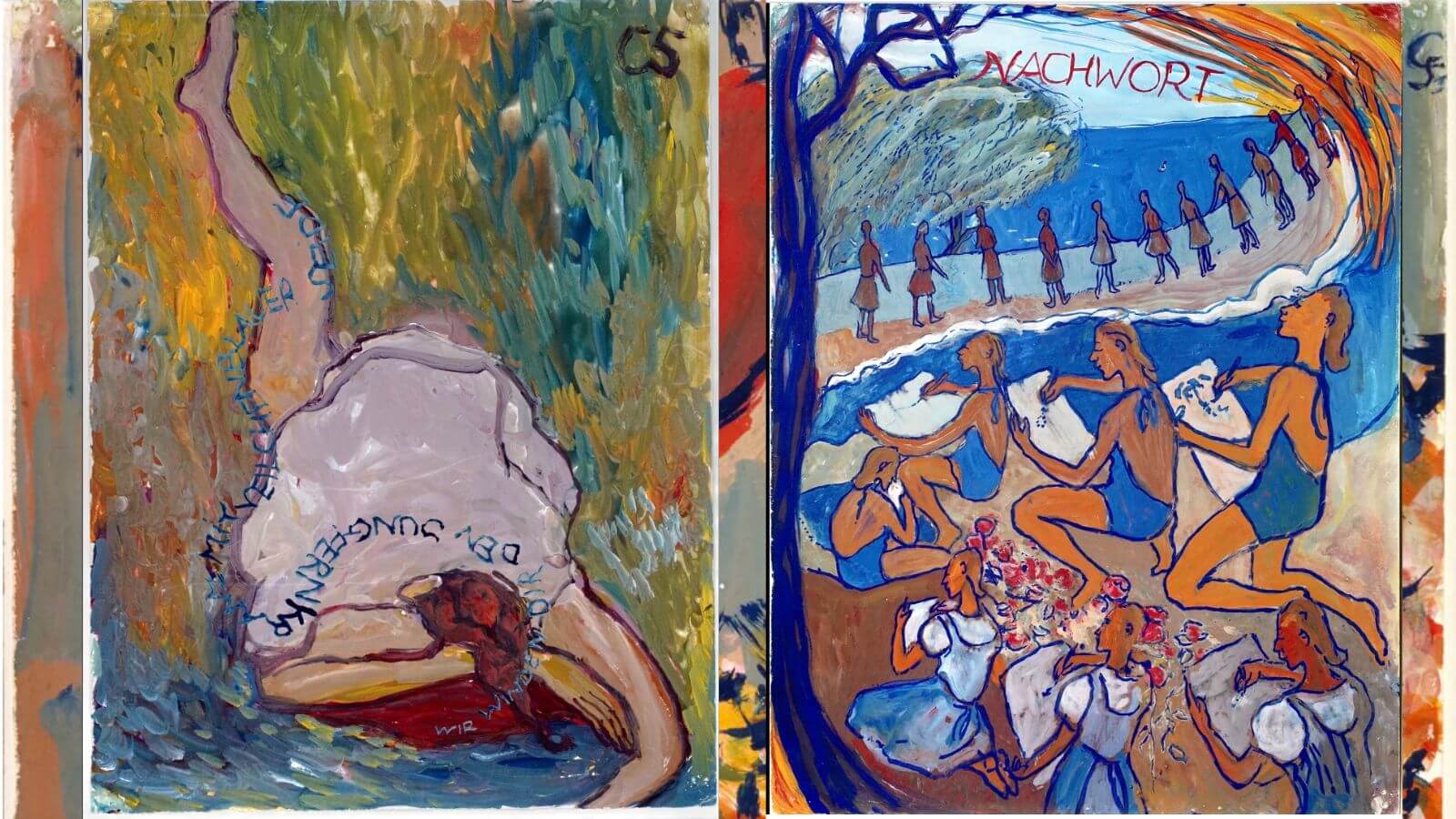

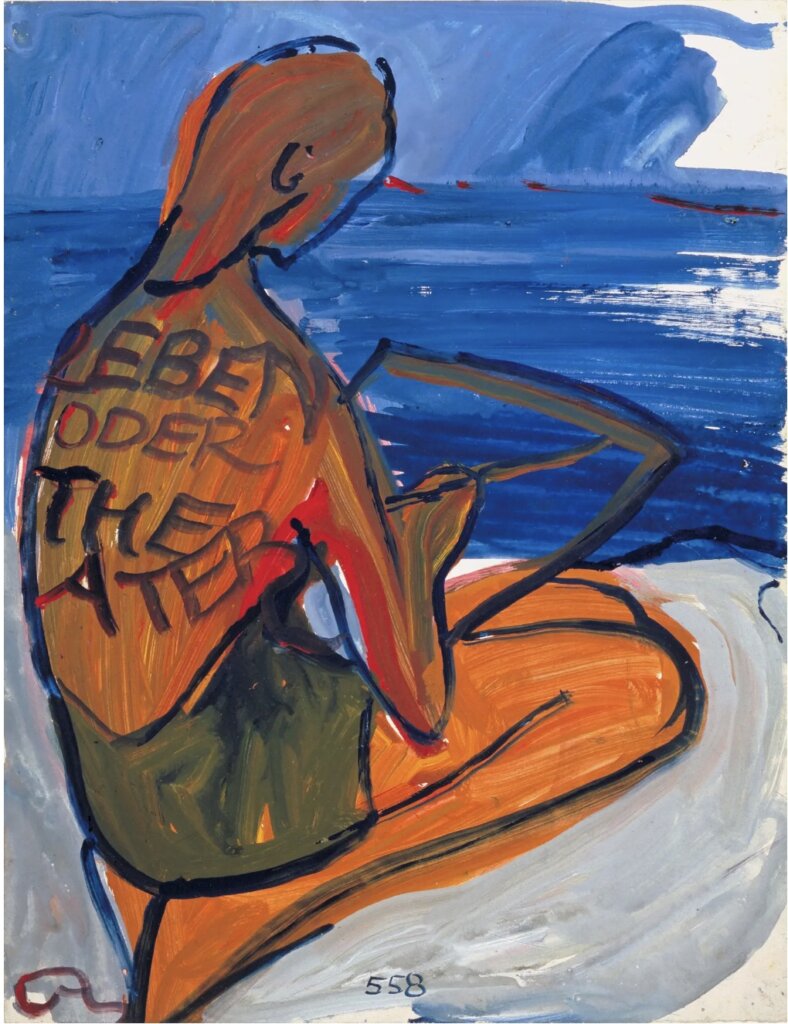

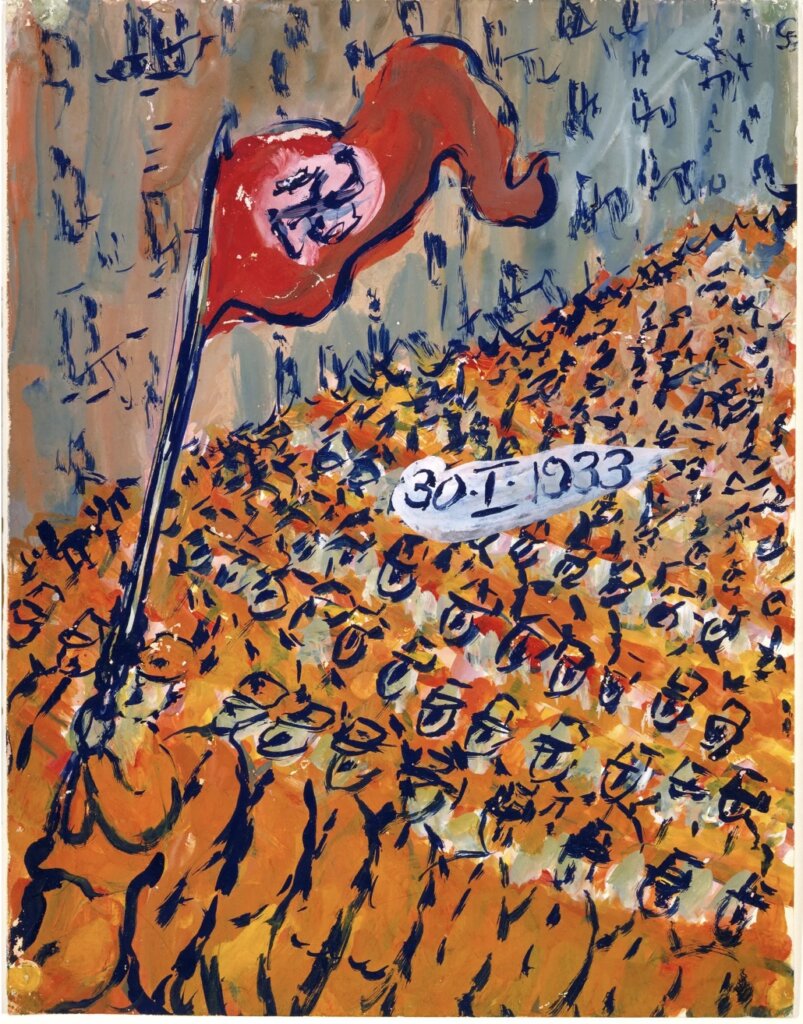

Salomon didn’t leave behind a diary full of musings on goodness and teenage love; instead, she left hundreds of vibrant, Expressionist gouache paintings with transparent overlays with which she added text and dialogue, as well as musical cues and notation detailing the songs she made up and sang to herself as she painted, all compiled into a piece titled Life? Or Theater? In the lightly-fictionalized work, Salomon tells the story of her life, including family dysfunction, multiple suicides, and her toxic love affair with a man 21 years her senior.

And, in a 35-page confession scrawled in all-caps with rusty-colored paint — and excised from the work by her parents — she confesses to murdering her own grandfather, who sexually abused her, feeding him a “Veronal omelet” full of barbiturates and sketching him as he died.

Now, directors Delphine and Muriel Coulin have brought the libretto-like Life? Or Theatre? to the screen, with voice actors reading and, where indicated, singing Salomon’s dialogue and narration as the camera pans over her paintings.

Marketed rather misleadingly as a documentary, Charlotte Salomon: Life and the Maiden gives little information about the artist aside from what she, herself, wrote, and little to look at outside of her paintings. It is less movie, more state-of-the-art installation technique, allowing viewers to access Salomon’s work acted out the way she, perhaps, imagined it. (Due to its hundreds of pages, Life? Or Theater? is nearly impossible to display in a gallery or museum.)

But for some reason, despite their otherwise strict adherence to Salomon’s work, the Coulin sisters, like Salomon’s parents, removed her confession, which came to light in 2011.

It’s a confusing choice in a film that otherwise remains stubbornly faithful to the artist’s work. There’s almost nothing to contextualize Salomon, and no commentary on her art. All we get is a brief introduction, less than a minute long, telling the viewer that Salomon, then living in the south of France, arrived on her doctor’s doorstep in 1943 with a box containing 1300 paintings and hundreds of pages of text and even music — a feverish year and a half of work — and entrusted him to keep it. From there, the first page turns, and we enter Life? Or Theater?, where we remain for just over an hour.

The film is so committed to using only Salomon’s work that the visuals are limited to shots of her paintings, the camera zooming in slowly to provide a sense of movement — a technique which also frustratingly prevents the viewer from seeing the entire panel. (In a slight concession to audience needs, the paintings are occasionally animated in small ways, and there’s a smattering of stock archival footage providing some dynamism to the otherwise static set of images.) None of this takes away from the ambitiousness of the undertaking, but it does grate, at times, with the chosen medium.

So why, when the film holds to Salomon’s work so faithfully despite all of this, does it excise this startling and disturbing piece of information from Salomon’s already startling and disturbing piece of art? After all, Salomon’s loathing for her grandfather is still obvious. After being transported on a crowded train car to a labor camp — she was later released — she writes that she would rather do it 10 more times than spend a single night with her grandfather. In one gouache, he stands, scrawny legs sticking out of a nightshirt, and tries to coerce her into bed with him, telling her it’s “natural.”

Admittedly, we don’t know if the confession is true — if Salomon actually poisoned her grandfather or merely fantasized about it. Her confession is written in the same all-caps, painted scrawl that she uses in the rest of the libretto, implying that it, too, could be a surreal mix of dream and reality. But the same could be said of the love affair with her stepmother’s singing teacher, which dominates the middle of Life? Or Theater?, or her use of pseudonyms such as the singsong “Paulinka Bimbam” for her stepmother, a contralto. Even her grandfather’s abuse could potentially be fiction. The film doesn’t fact check any of that — so why draw the line at his murder?

Life? Or Theater? is a record of Salomon’s attempts to grapple with her own psyche, and the darkness of her life and family history. Fact and fiction, in this case, mix to give insight, not to obscure it; even her pseudonyms reveal her feelings for those they label. The murder, real or imagined, fits perfectly with her constant struggle between life and death. In choosing death for her grandfather, she freed herself to live life. Morally, it’s muddy — but artistically, it makes perfect sense.

Charlotte Salomon: Life and the Maiden premieres at the New York Jewish Film Festival on Jan. 18.