A family and a writer plagued by the aftershocks of Holocaust trauma

in ‘The Absent Moon,’ Luiz Schwarcz writes of survivor guilt and his own depression

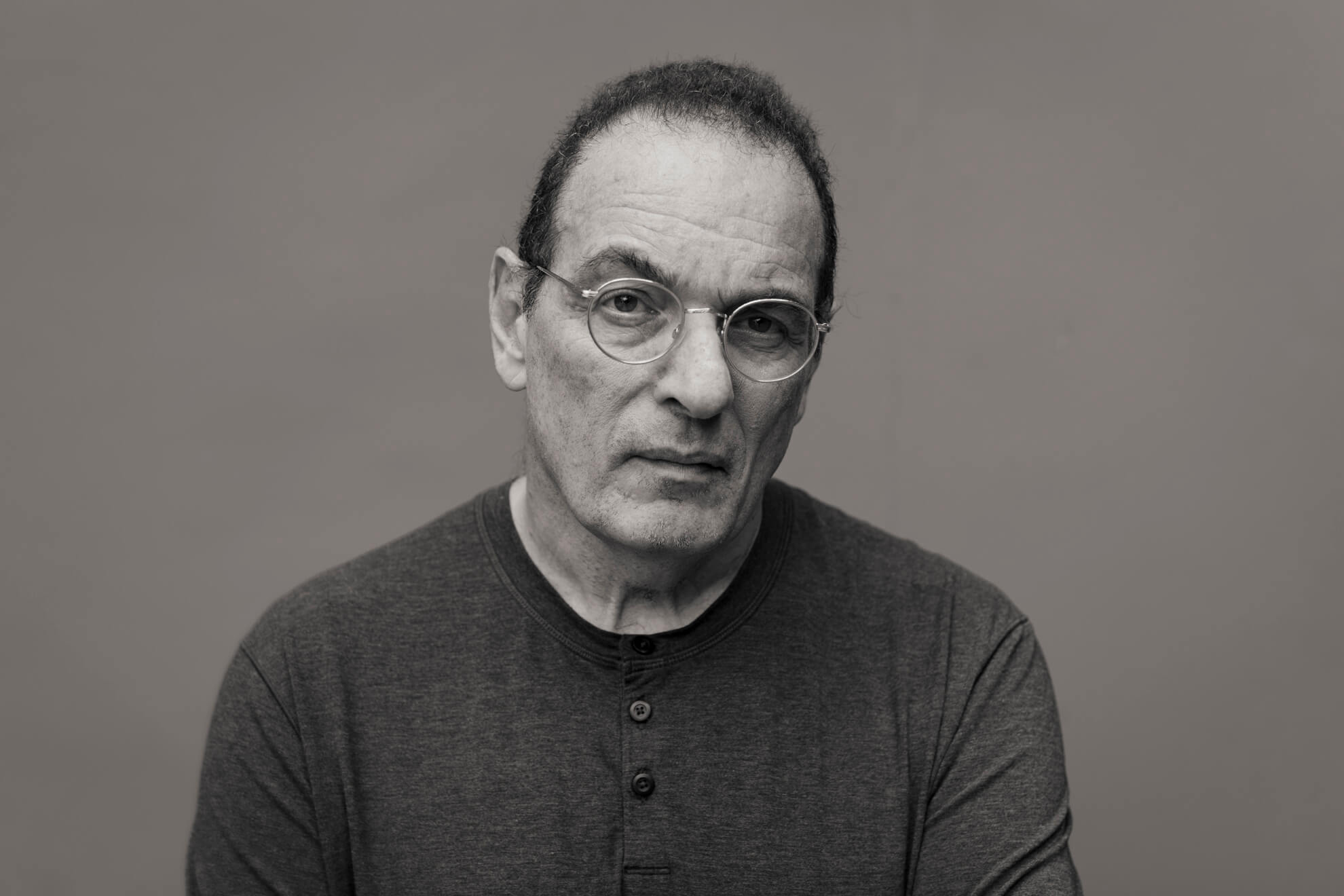

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The Absent Moon: A Memoir of a Short Childhood and a Long Depression

By Luiz Schwarcz; translated from the Portuguese by Eric M.B. Becker

Penguin Press, 240 pages, $28

The depression that afflicts the Brazilian publisher Luiz Schwarcz is catastrophic and disabling, kept at bay, he tells us, only by a potent mix of medications and therapy. It also seems overdetermined, the result of both genetic factors and environmental stressors whose impacts are impossible to disentangle.

In his meandering, idiosyncratic memoir, The Absent Moon, an evocative title that summons up varieties of darkness, Schwarcz chronicles a family history scarred by Holocaust trauma, his parents’ grim marriage and the emotional burden he carried as a child tasked with bringing them joy.

“I felt caught between my father’s complaining, my mother’s doting, and declarations by both of their love for their only child,” he writes. “Twisted in one direction and then the other, I wasn’t sure I could rely on those who ought to have been my first heroes and role models in life.”

Neither, despite his relative privilege, could he rely on the Brazilian healthcare system, which botched both a hernia surgery and his mental health treatment. His depression, he says, was misdiagnosed and poorly medicated until doctors finally realized he suffered from bipolar disorder.

That malady has strong genetic roots, but is often triggered by trauma or stress, and it requires a different set of meds than depression alone. Schwarcz comes surprisingly late to lithium, often the treatment of choice for bipolar disorder (in combination with antidepressants), and pronounces it “the best mood stabilizer I’ve ever tried.”

According to its jacket copy, Schwarcz’s memoir, ably translated from the Portuguese by Eric M.B. Becker, was “a literary sensation in Brazil.” If so, that may be because of the combination of Schwarcz’s national celebrity and his unvarnished frankness. Founder of the São Paulo publishing house Companhia das Letras, Schwarcz has authored two children’s books and two short-story collections, and in 2017 received the London Book Fair Lifetime Achievement Award. Those credentials won’t mean much to the U.S. reader.

More germane and universal are Schwarcz’s mental health struggles, which incapacitated him at times and led to self-harm. He introduces the concept of “depressive totalitarianism,” an insistence that everyone around him dedicate themselves to his needs. “In this intense period,” he writes, “my attacks of guilt mingled with depressive thoughts, spurring prolonged weeping episodes in a vicious cycle that demanded endless patience on the part of my wife and children.”

Schwarcz writes with equal candor of his early sexual misadventures and various intimate family matters. He reveals that his father, André, sent him to prostitutes shortly after his bar mitzvah, an experience more upsetting than pleasurable. His mother, Mirta, endured repeated miscarriages (and one tragic stillbirth). His father raged, resorted to sex workers, and at least once escalated to domestic violence.

The generational aftershocks of Holocaust trauma still plague the family. A Hungarian Jew who found a new life in Brazil, André never overcame his particular species of survivor guilt. His father, Lajos, had either ordered or pushed him off a Nazi transport to Bergen-Belsen. At 19, he managed to escape, while Lajos ended up in the camp and died shortly after its liberation. Luiz, named for Lajos, dedicates the memoir to his grandfather.

André (whose mother and sisters survived the war) continually mourned his father. His Yom Kippur prayers were filled with tears and repentance. He suffered from insomnia and wild mood swings and underwent electroshock treatment and therapy.

By contrast, Mirta’s parents both made it from Yugoslavia to Brazil, and Schwarcz’s maternal grandparents figured importantly in his life, confiding in him and spoiling him. Unhappy with Mirta’s marriage, they “harbored a silent animosity” towards André.

Silence turns out to be one of the principal themes of the book. “Life was quiet, solitude was the norm, and underneath it was an all-consuming fear,” Schwarcz writes. His depression may have surfaced initially during his teenage years, he says, but soccer — he was a talented goalie — and involvement in the Jewish youth movement were great escapes.

Even more essential, he makes clear, has been his fortunate and lasting marriage to his childhood sweetheart, Lili. He also has leaned on his love of reading, a gift from his mother, and of music, an inheritance from his father. He collects records obsessively, perhaps a marker of his manic tendencies. He touts the benefits of psychoanalysis and exercise.

And he writes at some length of his failed, unpublished novels. The title of this memoir is lifted from one of them, a fictional recounting of his father’s life.

In The Absent Moon, as in memory, time dissolves, and past and present often merge. One instant, Schwarcz is alongside André in their synagogue. In the next, he is alone, but speaking to his long-dead father of his sorrows. These are the memoir’s most powerful moments.

“This book was built upon a long history of silences,” Schwarcz writes in an epilogue. “But the stories told here were in need of an outlet.” He shares them, he says, “in the hope that I might now go back to reading.”