Did hubris and ridiculous lyrics doom what could have been a rock ‘n’ roll sensation?

T. Rex’s ‘Tanx’ should have been a smash in 1973. What did Marc Bolan get wrong?

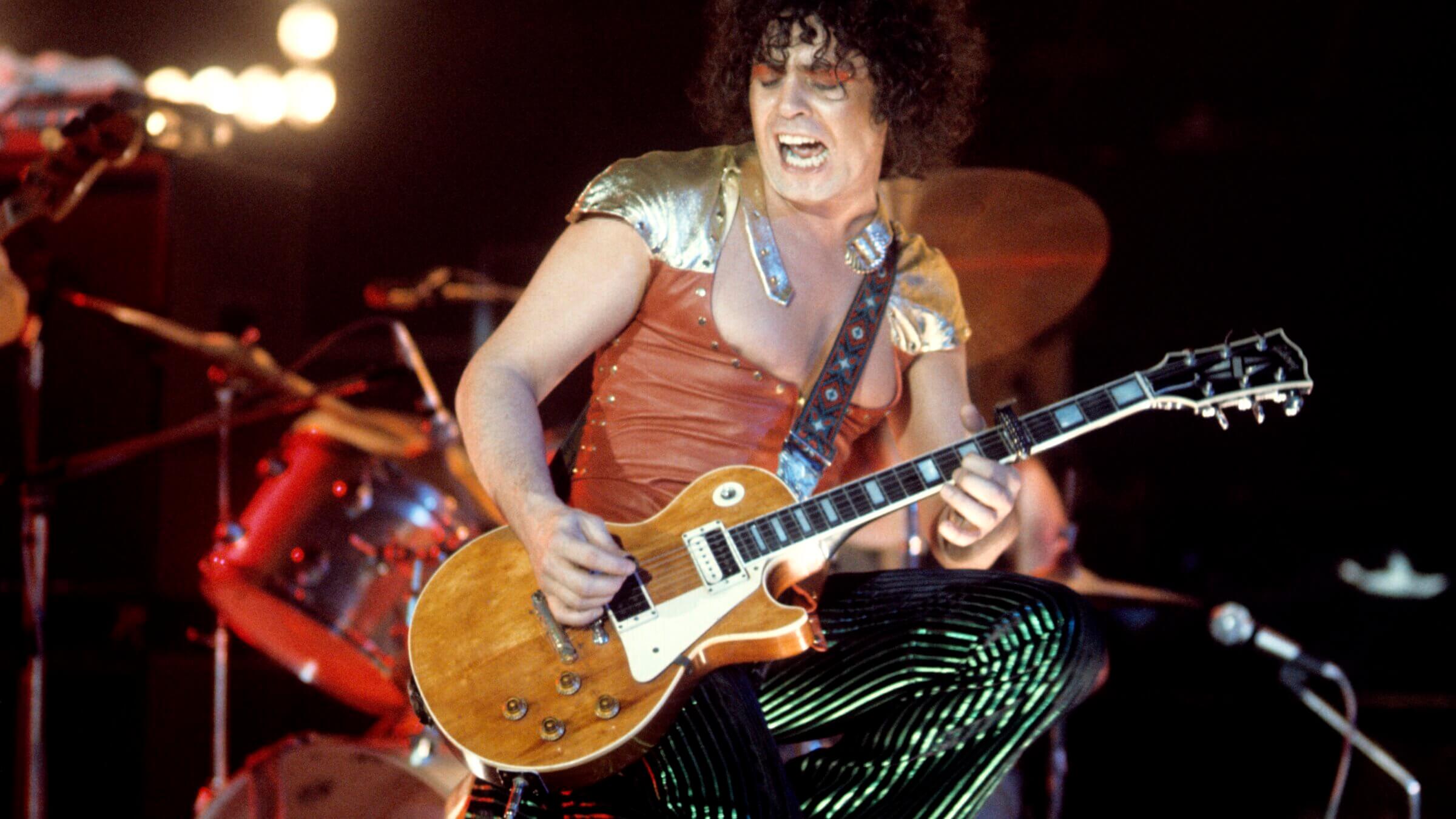

The son of a Russian-Polish Jewish lorry driver, Marc Bolan willed himself from a working-class East End existence to musical superstardom in less than a decade. Photo by Getty Images

For Marc Bolan and his band T. Rex, 1972 had been the most fabulous year yet. The Slider, their seventh studio album (and third since the band’s name had been abbreviated from the original Tyrannosaurus Rex), had been an international smash, their first full-length to pierce the Top 20 in the U.S. The album produced two chart-topping U.K. singles — the delightful glam rock anthems “Telegram Sam” and “Metal Guru” — which were followed by two non-LP hits, “Children of the Revolution” and “Solid Gold Easy Action,” both of which stomped their way to Number 2 in the U.K. charts.

The year had ended with the celluloid victory lap of Born to Boogie, a film directed and produced by Ringo Starr, which intercut surreal fantasy sequences with studio jam sessions and footage from T. Rex’s hysteria-ridden March ’72 concerts at the Wembley Empire Pool.

The former Beatle’s patronage reinforced Bolan’s standing as Britain’s biggest and brightest star since the dissolution of the Fab Four, and further bolstered his seemingly unlimited supply of confidence and ambition. The pint-sized son of a Russian-Polish Jewish lorry driver had already willed himself from a working-class East End existence to musical superstardom in less than a decade; and now, as he entered 1973, Bolan’s sights were set on even greater triumphs.

During a Belgian TV interview early in the new year, Bolan spoke of collaborating with Starr on an upcoming sepia-toned silent movie — “A very surreal sort of film, very sensual” — while also expressing his belief that cultural change would only come about with rock stars like himself leading the charge.

“There’s been a lot of talk about revolutions,” he said. “The only revolution that’s going to happen is if people like myself or Mick Jagger or Rod Stewart or whoever try to get into other fields — be it television, be it movies. Then we will get a revolution. If it’s left to other people, there will be no revolution.”

T. Rex’s first single of 1973, “20th Century Boy,” was another blast of Bolan brilliance — a brash, instantaneously catchy come-on riding a blaring sax and a fabulously crunchy guitar riff to rock ‘n’ roll nirvana. Released on March 2, the single was followed two weeks later by Tanx, an album that should have launched T. Rex even further into the stratosphere; in retrospect, however, it’s where the wax on Bolan’s Icarus wings began to melt.

For all of Bolan’s public bravado, he’d been frustrated in 1972 by his inability to fully “break” in America. T. Rex had found a rabid following in New York City and Los Angeles, as well as in Midwestern rock n’ roll strongholds like Detroit and Cleveland, but getting through to a wider audience was a real challenge. At a time when American rock fans tended to gravitate toward music that was either very heavy or very mellow, T. Rex’s whimsical boogie seemed like little more than an exotic curiosity.

Back home in England, the increasing hostility of the music press towards Bolan and his music had him on the defensive. Especially rankling was the critical consensus that T. Rex’s latest hit singles all sounded the same, and that The Slider had been little more than a carbon copy of 1971’s Electric Warrior. (While it’s true that those two records do sound like they were cut from the same glittery cloth, they are also now generally regarded as two of the greatest and most influential albums of the original glam-rock era.)

So while Tanx was recorded at the same studio (France’s Château d’Hérouville) as The Slider, with the same personnel (longtime producer/collaborator Tony Visconti, the T. Rex rhythm section of Mickey Finn, Steve Currie and Bill Legend, and backing vocalists Flo & Eddie, aka. Howard Kaylan and Mark Volman of The Turtles and The Mothers of Invention), Bolan was determined to take at least some of his music in a bold new direction.

“Tenement Lady,” the two-part, Mellotron-drenched psychedelic reverie that opened the album, might not have been the catchiest option for a lead-off track, but it certainly served notice that Tanx wasn’t going to be The Slider Part 2 or Electric Warrior Vol. 3.

But dreamy psychedelia wasn’t where Bolan was heading — American soul music was, as reflected by a significant portion of Tanx’s 13 tracks. Featuring the work of session saxophonist Howie Casey, who had previously wailed on “20th Century Boy,” songs like “Mister Mister,” “The Street & Babe Shadow” and the nakedly emotional “Broken Hearted Blues” offered up an intriguing fusion of glam and R&B, a vein which Bolan’s friend and arch-rival David Bowie would mine to tremendously successful effect two years later with his Young Americans LP.

But the world wasn’t quite ready for such a groundbreaking combination in 1973, and Bolan’s propensity for writing ridiculous lyrics didn’t help things any. With its soulful melody and a gorgeous Tony Visconti arrangement that wouldn’t have sounded out of place on a Spinners album, “Electric Slim and the Factory Hen” could have been a massive crossover hit if it had featured something approaching a relatable lyric. Unfortunately, abstruse lines like “Me, I’m loose like a golden goose/You can have my juice” and a chorus of “Steady old soldier/Watch what you’re doing to my girl” just weren’t going to put it over the top with AM radio listeners.

And then there’s the album-closing “Left Hand Luke and the Beggar Boys,” which wastes a stirring gospel meditation on lines like “Myxomatosis is an animal’s disease/ But I got so shook up Mama that it ate away my knees.” Delivered by someone as obsessed with commercial and critical success as Bolan was, these bizarre lyrical excursions seemed driven by either sheer hubris or utter self-sabotage.

The other problem with Tanx was that Bolan couldn’t resist keeping one stack-heeled foot in the classic T. Rex sound that had proved so successful over the previous two years. While the album contained some truly wonderful tracks — including “Rapids,” “Mad Donna,” “Born to Boogie” and “Highway Knees” — that wouldn’t have sounded out of place on Electric Warrior or The Slider, their presence made it easy for critics to once again accuse Bolan of repeating himself. Even Billboard magazine, in an ostensibly positive review of the album, completely ignored its more soulful and experimental elements.

“Marc Bolan and his boys are back with a set of what they do best — straight, unpretentious rock,” the reviewer wrote. “Possibly the best way to describe this LP is to call it a package of 13 potential hit singles.”

Which, even by Billboard’s back-slapping standards, was outrageously optimistic. In fact, Reprise Records, T. Rex’s American label, had no idea what to do with Tanx. While the album rose to Number 4 on the UK albums chart, it didn’t even break into the Top 100 in the U.S., a tremendous comedown from The Slider’s glide to Number 17. No singles from the album would be released on either side of the Atlantic. “The Groover,” a non-LP single recorded after the Tanx sessions, made it to Number 4 on the UK singles charts in the summer of ’73, but it was also the last time that Bolan would reach the UK Top 10.

Fellow glam rockers Slade, The Sweet and Gary Glitter were all overtaking T. Rex in the British charts, while David Bowie — who dramatically retired his Ziggy Stardust character that July — was receiving the critical plaudits and respect that Bolan craved.

With his star beginning to wane at home, Bolan made another attempt to break America, spending over a month here on tour and even making a September appearance on NBC’s The Midnight Special. Instead of playing something from Tanx, however, Bolan opted to perform two older hits on the TV show — “Hot Love” and “Bang a Gong (Get It On)” — with a lineup augmented by second guitarist Jack Green and backing vocalists Gloria Jones and Sister Pat Hall.

Though the fiery (and quite possibly coked-up) performance is still exciting to watch, it also rather pointedly demonstrates the quixotic futility of Bolan’s American conquest. His extended guitar solos are way too sloppy to impress American rock fans obsessed with the proficient likes of Eric Clapton or Jimmy Page; and thanks to the excess poundage of alcoholic indulgence, the lithe, sexy elf of yore now resembles a demented homunculus — especially when he takes off his guitar and proceeds to punish it with a whip as the stage fills with dry ice smoke.

Bolan’s commercial picture would not get any prettier from here. Within a year, he would be dropped by Reprise and part ways less than amicably with nearly everyone in the T. Rex camp — most crucially Visconti, who had produced every T. Rex and Tyrannosaurus record going back to 1968. Bolan unquestionably found romantic happiness with Jones, a talented singer and songwriter whose discography included the original 1964 recording of “Tainted Love” (later a 1981 smash for Soft Cell), but the soul-influenced albums he made with her as his muse and main collaborator were massive flops and remain quite controversial among Bolan fans to this day.

Bolan would find renewed commercial and critical favor in 1977, thanks to the more rock-oriented album Dandy in the Underworld and a weekly Granada TV series that featured performances by various British punk bands, but he sadly died in a car crash that September, just as his comeback was really getting underway. He was just two weeks shy of his 30th birthday.

Fifty years after its original release, Tanx remains a strange but fascinating beast. Though the album tends to be overshadowed by T. Rex’s two previous LPs, it actually holds its own with them quite well. (“I love Electric Warrior, Slider and Tanx,” Visconti raved in a 2016 interview. “Like David Bowie has his trilogy, that’s Marc’s.”) On the other hand, it also represents the exact point on the T. Rex timeline where the giddy fever of “T. Rextacy” began to break — and there aren’t too many other albums where you can hear a talented artist breaking exciting new ground, while simultaneously beginning to lose the plot.