Spurred by religious faith, an angelic evangelist became a savior to Jews

In ‘The Watchmaker’s Daughter,’ the heroic story of Corrie ten Boom

Corrie ten Boom, flanked by Pat Boone and Billy Graham at the film premiere of The Hiding Place, 1975. Photo by Getty Images

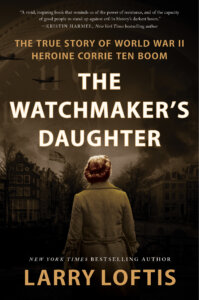

The Watchmaker’s Daughter: The True Story of World War II Heroine Corrie ten Boom

By Larry Loftis

William Morrow, 384 pages, $33

The closing pages of The Watchmaker’s Daughter feature a confrontation so improbable that it seems the stuff of fiction. Having survived World War II, Dutch Resistance heroine Corrie ten Boom finds herself face to face with a man she had known as a particularly sadistic SS guard at the Ravensbrück concentration camp.

A devout Christian, ten Boom has been traveling the world preaching a message of postwar healing. After a talk at a Munich church, the erstwhile guard informs her that he, too, is now a Christian and regrets his wartime cruelty. But when he requests her forgiveness, even the angelic evangelist hesitates.

A onetime corporate lawyer, author Larry Loftis has turned to writing gripping narrative nonfiction. Following the thread of a World War II spy saga led him to the ten Boom story. The result is a stirring, cinematic, religiously infused tale of ten Boom and her family, who risked their lives during the Nazi occupation to save Dutch Jews, Resistance members and others.

A bestselling, ghostwritten 1971 memoir, The Hiding Place, later made into a film and a stage musical, told Corrie ten Boom’s story. She also chronicled her life in other books. But Loftis decided that, with the help of additional primary sources, he could offer a more nuanced and detailed account. Both Anne Frank’s celebrated diary and the recollections of the Dutch-born actress Audrey Hepburn figure in The Watchmaker’s Daughter. So, too, does the memoir of Resistance operative Hans Poley, who sheltered with the ten Booms for a time.

As World War II morphs from memory to history, we’re learning more about rescuers and resisters, and the diversity of their characters and motives. In the case of the ten Booms, the spur to their courage was a religious faith so potent that, on occasion, it helped convert even their captors.

It’s not necessary to be a believer to be impressed by the strength ten Boom and others derived from their belief in the Gospel. In the bowels of two different concentration camps, ten Boom, with her sister Betsie, led worship services and ministered to other prisoners.

The book’s title is misleading: Corrie ten Boom was not just the daughter of a watchmaker; she was herself a skilled craftsperson, the first Dutch woman to be licensed as watchmaker. Even before war led her to the Resistance, she seems to have been an exceptional person determined to choose her own path, with the support of a close and loving family.

After the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands, the middle-aged, never-married ten Boom and her family stepped up. They offered the residence above their Haarlem watchmaking shop, known as “the Beje,” as a safe house. Both Jews and non-Jewish Dutch people (“divers”) on the run from the Nazis sought refuge there. Some stayed only briefly, others for months or years.

While Anne Frank reported the squabbles and tensions in her family’s secret Amsterdam annex, Loftis suggests that the Beje, even as it grew crowded, remained a harmonious assemblage. Though lacking central heat, the place, he writes, was blessed by “a warmth and happiness … that few Dutch homes enjoyed.” The ten Booms offered refugees “deep, abiding, and unconditional love,” Loftis says. Several photographs seem to attest to the amity of the group.

The ten Booms’ activities included encouraging the theft of ration cards and helping to rescue Jewish children. Outside their home, the Nazi repression worsened, and the deportations of Jews to death camps continued. Corrie’s sister Nollie (who lived elsewhere) was arrested in 1943 when she admitted to harboring Jews. In 1944, after Corrie trusted a man she shouldn’t have, the Nazis arrested the residents of the Beje and many fellow Resistance operatives.

Their fates diverged. A Gestapo officer offered to release Corrie’s beloved father, Casper ten Boom, nicknamed Opa, if he promised to change his ways. “If I go home today, tomorrow I will open my door again to any man in need who knocks,” he reportedly responded. He died in prison just days later. “We will meet again in God’s time,” Corrie wrote in her journal.

Corrie and Betsie ended up first at Vught, a concentration camp in the Netherlands, and then Ravensbrück, a women’s camp in northern Germany, “notorious for cruelty, brutality, and executions.” The sisters worked as slave laborers, and endured lice, fleas, overcrowding, bitter cold and starvation rations. Betsie eventually sickened and died. But Corrie, having survived pleurisy and tuberculosis, and deathly ill once more, was unexpectedly released — the fortunate result of a clerical error.

She spent the postwar years fulfilling a vision she had shared with her sister: setting up places of refuge and healing in the Netherlands and Germany, not just for Dutch concentration camp survivors but for Dutch wartime collaborators and displaced Germans.

Loftis tells the story uncritically, from the perspective of ten Boom and others on the side of right. Apart from a few infelicities, the book’s prose is crisp, the pacing fast, the narrative compelling. Loftis’s own viewpoint isn’t tough to discern. By the time ten Boom confronts that repentant concentration camp guard, we suspect that faith, once again, will conquer all.