Peter Gabriel’s not-so-secret Jewish weapon — and his little side project called King Crimson

When the rocker goes out on tour for the first time in a decade, Tony Levin will be there alongside him

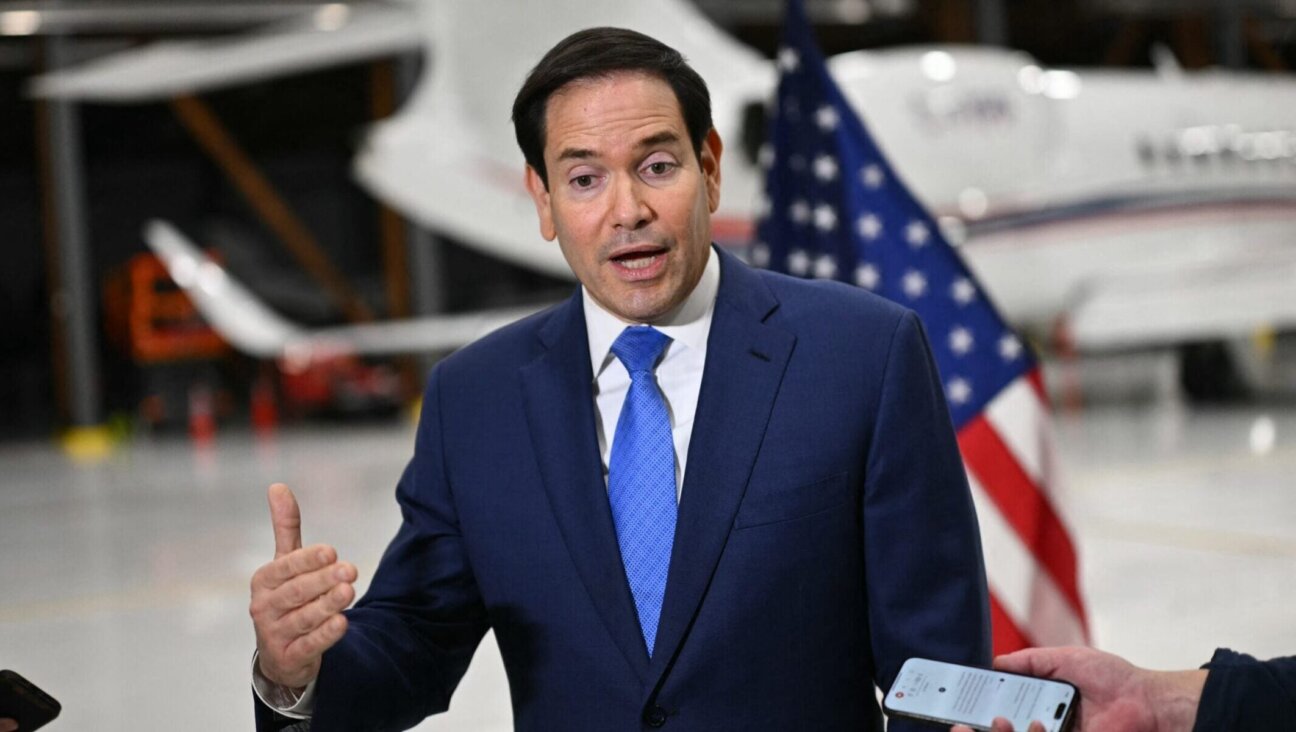

Tony Levin performs with Peter Gabriel in 2014. Photo by Getty Images

Tony Levin doesn’t remember the exact day — his memory’s not that good — but it was a fortuitous one. You could call it a life-changer.

It was July 1976, and Levin, a rangy, 30-year-old bassist, had been working steadily in New York as a session man. He got a call from record producer Bob Ezrin, with whom he had worked on Lou Reed and Alice Cooper records, to go Toronto for a session.

“He called me in to play with this ‘new guy’ Peter Gabriel, who had left this band, Genesis,” Levin told me, speaking from his home in Kingston, New York. “I had heard the name of the band, but I had not heard Genesis in those days.”

His initial impression: “What I remember was I was very interested in being introduced to this new kind of music that this young Peter was writing. It was very different from anything I had heard. I didn’t put it in that category of ‘progressive rock’ because I wasn’t very interested in genres. His chord structures and the way of going about writing a song was very different than anything I had run into. I thought it was fascinating.”

Not only did he meet Gabriel — with whom he would continue to collaborate in the studio and tour with for four-plus decades — he met guitarist Robert Fripp, a friend of Gabriel’s who was also playing on the singer’s solo debut.

That led to a long-term stint in Fripp’s band, King Crimson. At the time, Fripp had put King Crimson to bed. Permanently, it seemed. But, said Levin, “Robert asked me to play on his solo album Exposure and that led him to asking me to be in a new band which was going to be called Discipline, but became [another edition of] King Crimson.”

At this initial gathering — meeting with Gabriel and Fripp — did any lightbulbs go off?

“No lightbulbs went off because I’m a slow lightbulb guy,” said Levin, with a laugh —he’s just back from a five-week tour with another of his bands, Stick Men. “Put a different way, I didn’t realize that forty years later I would still be making very special music with these guys.”

Up until the initial Gabriel hookup, Levin went on the road sometimes with jazz bands, but the problem was, in his studio world: out of sight, out of mind. “In those days,” Levin said, “you didn’t leave town because if you left town, you would lose work.”

But Gabriel made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. “At the end of the session, having finished the album, Peter asked if I would do the U.S. tour to introduce the album and I jumped on it.”

Neither Kojak nor Yul Brynner

I saw the Boston stop of that tour at the Paradise rock club, Halloween 1978. Gabriel entered from the rear of the club, carrying a portable light, illuminating the audience. Band members, also toting spots, entered from other parts of the club, everyone winding their way to the stage. The message: We’re all in this together. And the music was brilliant, all from Gabriel’s eponymous first two albums, save one Genesis song, “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway.”

Standing 6-foot-2 with a shaved head, playing an odd, long and straight instrument called a Chapman Stick, Levin was a formidable figure on stage. “When I first shaved my head, people were so unused to that,” he said. “Some people on the street would say, ‘Hey Yul!’ and a few years later, ‘Hey Kojak!’ Pretty amazing to think that it was a time when being bald was that rare, not to mention people being so unfiltered and rude, they have to say something. Well, maybe that’s still with us.”

One memory Levin retains; “My parents were at that show, and Tim Cappello, the sax player, was gyrating and maybe taking some clothes off, and I was thinking, ‘Gee, I wish he wouldn’t do that with my folks here!’”

There have been numerous sessions since making Gabriel’s first album — he’s played with John Lennon, David Bowie and Bryan Ferry — but he’s been a regular with Gabriel throughout his solo career. When Gabriel started writing and recording again a couple of years ago, he brought Levin over to London for the tracks that will make up Gabriel’s Full Moon project. It’s his first album of new music since 2002’s Up.

Gabriel started releasing a streaming track each month on the full moon — three so far. “He wants people to be aware of the moon and the world around us,” said Levin, who has played on all 16 songs. “I can attest that all of tracks are really special and his voice is fantastic. Peter thinks outside the box.”

Gabriel will be unveiling some of the songs on an upcoming arena tour called i/o. The European leg starts May 19 in Krakow, the North American leg kicks off in Quebec City Sept. 8.

Alas, Levin’s other main group, the Fripp-run King Crimson, is likely done, or, at the least taking a long nap.

“I know better than to speak for Robert,” Levin said, “but when I last was with him — the tour ended in Japan at the end of 2022 — we had a nice talk about the future and what might happen. His words to me were that he had no plans for King Crimson doing anything else, but he would let King Crimson speak to him if it chose to. I interpreted that to mean there are no plans and probably won’t be anything else, but it’s not impossible that there might be.”

Brought up in Brookline

Levin’s musical life began when he was a child in Brookline, Massachusetts. Same with his older brother, Pete, who continues to play keyboards with Tony in the Levin Brothers, another side project.

“Being in a traditional Jewish family, that was part of our education,” Levin said. “You must learn to play piano and after a couple of years you must choose an instrument. It was a culturally Jewish thing. After a few years of piano, I chose bass. I don’t know why. It was a very good choice for me because I am still captivated by doing that exact same thing, though my parents did not expect us to become professional musicians — I think doctor or lawyer would have been more in order.

“But they did their best to accept it and in their very elderly years it was a hoot seeing them come to a King Crimson concert or a Peter Gabriel concert and enjoy the rock music they’d never heard until I joined those bands.”

Asked whether Levin considers himself more culturally Jewish than religiously so, he said, “That’s a very good question. There are so many angles. I’ll do my best with it. I am, in many ways, aware I’m culturally Jewish. Growing up in Brookline, even if I hadn’t been Jewish I would have picked up the cultural Jewish ethics of that neighborhood.

“Growing up, I went to a Reform temple and took the religious part of it casually and I suppose I could say I still do. When I have done interviews in the old days, to answer the question ‘How Jewish are you?’ I answer, “Well, I feel like I’m Jewish but I eat BLT sandwiches.’”

Levin told me he recalled doing a phone interview with a journalist in Israel and, after the interviewer heard that answer, the line went quiet for a long time.

“The interview had changed,” he said, “and that person was no longer a fan of mine.”

A charmed life?

Next month, Levin will be in London where Gabriel will be assembling his troops for about a month, a stretch of time that Levin interprets to mean that the tour will be “very big, very special and groundbreaking. I’m a player in the band, but I’m also a fan, if you can imagine what fun that is.”

Has it been a charmed life?

“I’ve never put it in those words. but I’m aware at this point in my career I realize I’ve been extremely lucky in a number of ways,” he said. “The music industry is not always the easiest and many people can’t make it a living. In my book, if you can make a living from it and play some decent music, yes, you have a charmed life.”

Levin, who has also written a collection of bass-related stories and anecdotes, a poetry collection and, most recently, a book of black-and-white tour photographs, will turn 77 in June and says he has no plans to lay his instruments down.

“Life will undoubtedly impose some rules on me I haven’t thought of,” he said, but “I’m lucky to have my health and what musicians want is to keep doing what we do. The people who can’t understand that are people never lucky enough to have a profession to occupy that part of your mind and life. It’s big for anybody in the creative field.”

When he’s on stage, Levin is in his element. Like many touring musicians, he puts up with the other 22 hours of the day – the bus rides, the irregular eating schedules, the sleep-as-catch-can, the grind of the road – for those two hours on stage.

I asked him if, when he’s up on stage, he thinks about the power of his music.

“Feeling it, yes,” he said. “Thinking, no. The only time I think about music at all is when I’m in an interview and I’m asked about it and then I have to reverse engineer the whole thing and decide what it is I’m even doing when I play. I’m aware when I play the song the musical part of my brain is lit up and awake and I’m immersed in that. You could call it a kind of Zen thing or a meditative thing, but I don’t look at it that way. I’m inside the music. I’m not using the logical part of my brain.”

“I’m very aware of the sense of the audience,” he adds. “I don’t react to the audience, but I have learned through the years, the audience gives us something very valuable. Sometimes it takes off and it’s better than all the other times — we’re like a tribe. That’s partly why having a career in music is so immensely satisfying. You’re not trying to fashion something in a logical way; You’re carried away by the music just the way the listeners are.”