Cathleen Schine will convince you to move to Los Angeles

The author talks about her newest book, her writing routine and the importance of a standing cocktail hour

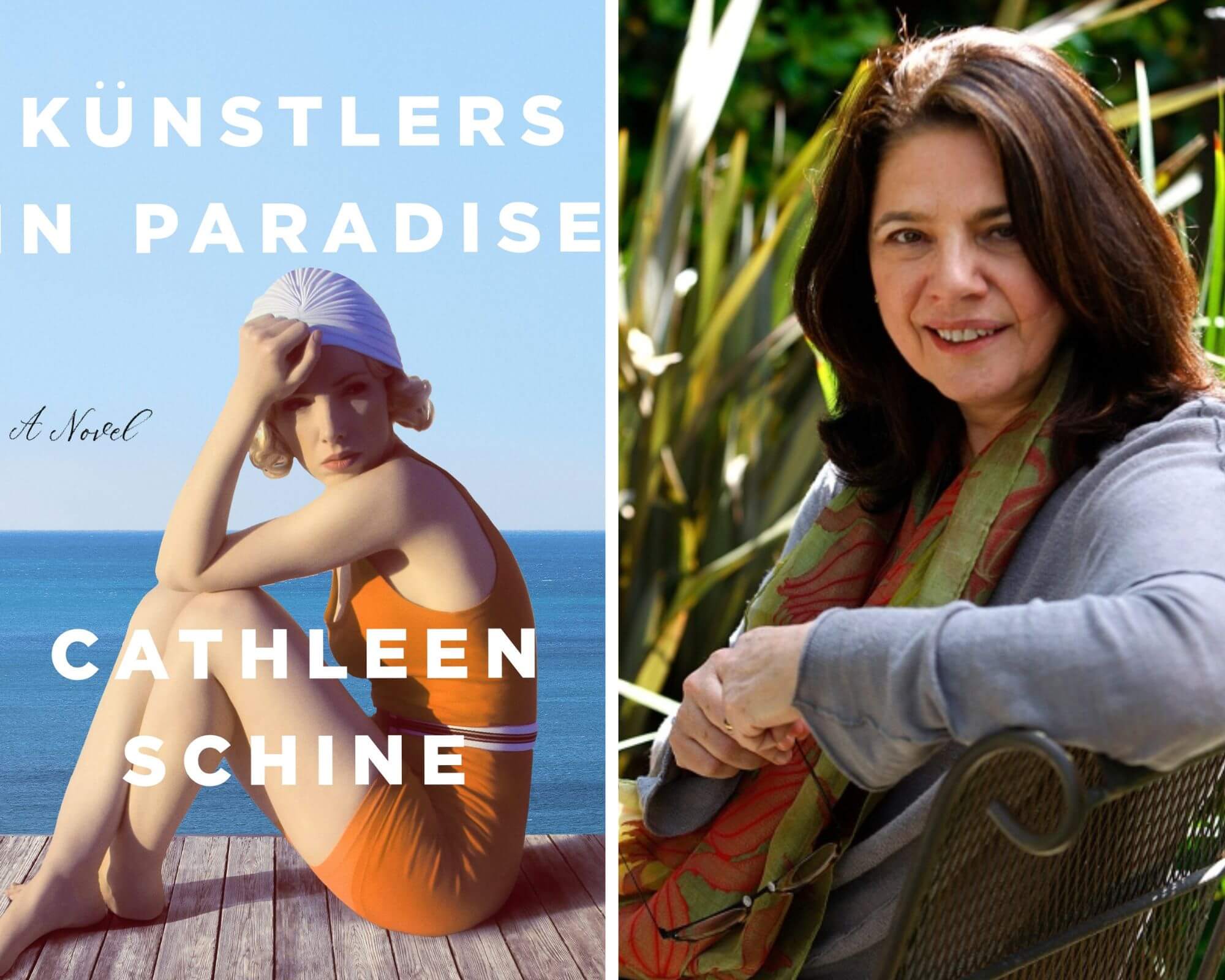

Schine’s latest novel, Künstlers in Paradise, is set in her adoptive hometown of Venice Beach, California. Photo by Getty Images

According to my father, you can tell a good book from its very first sentence. And while I don’t find this to be true in every case (I have been forced to contend that various Harry Potter novels sort of redeem themselves after banal openings), by this metric Cathleen Schine’s Künstlers in Paradise is an absolute winner. Schine’s twelfth novel opens as the Austrian Jewish Künstler clan arrives in Los Angeles, where they’ve fled after Hitler’s annexation of Austria. As far as bodies of water go, their only frame of reference is the Mediterranean Sea, and they find Venice Beach, their new home, very different indeed.

“They could spot dolphins leaping and playing from the beaches of Los Angeles just as they could from the rocks of Capri,” Schine writes, “but the Pacific Ocean was a noisy, industrious sea, working day and night in the manufacture of huge swollen waves, delivering them, one after the other, crashing, to the shore.” The image is enough to compel even a grumpy East Coaster like the writer of this article to admit that California might be a nice place to live.

To spouses Otto and Ilse Künstler, arrival in Los Angeles is a primal loss, not just of their elegant Viennese apartment but of an entire society and way of life in which they once felt secure. For 11-year-old Mamie, the novel’s narrator, it’s the start of a grand adventure. A bewildered child among equally bewildered adults, she befriends luminaries like Arnold Schoenberg in the city’s swelling enclave of Jewish refugees. And she acts as her family’s representative to the American world, translating for them and dutifully teaching them the slang she picks up at school.

But while Künstlers in Paradise opens in 1939, the action takes place in 2020, when Mamie, now a tough nonagenarian with a serious cocktail habit, is confronted by the coronavirus pandemic. Her companion for this global catastrophe is her grandson Julian, a coddled college graduate whose parents send him to Los Angeles just weeks before the first lockdown, in hopes that he can find a job and stop bothering them for rent money. Instead of embarking on an illustrious career, Julian finds himself making masked grocery runs, facilitating Zoom seders and writing down his grandmother’s stories. Mamie isn’t always easy to live with, but she might be exactly the person to usher Julian through his own difficult coming-of-age.

I reached Cathleen Schine at her home, which, like Mamie’s, is located in Venice Beach, California. We talked about the challenges of writing historical fiction, the best office spaces and (not) writing every day. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me a little about your writing routine.

I have many different routines, and it really depends on what age I am. With the first book, my process was very particular: I was working as a part-time copy editor at Newsweek, when Newsweek was a real magazine, and they had this big Lazy Susan, the copy would go around, and you’d grab some pages. But there were hours when nothing was there. And so I would just try not to attract too much notice and write on little scraps of paper. I basically wrote my first novel that way. For the next book, I had little children, so I just wrote whenever I could.

The one thing that seems to be consistent is that I like to do research, sometimes for months and months, and in this case for years. Which was a way of not having to write, and to become familiar enough with my characters to write them without feeling like a complete fraud. I so admire people who get up every day and write a certain number of words or hours. I just don’t do that. I don’t even know if you can call it a process. We’ll call it an unfolding.

What makes a good workspace for you?

My most productive time writing was when my cousin Betsy had a fifth-floor walk-up in the East Village that she couldn’t really afford. I helped her with the rent and used it as an office during the day. Walking up those five flights of stairs was like, I was not going anywhere. Although there was a bed, which meant I could nap, which is another way of not writing.

Did the pandemic change the way you write?

I never in my life had any kind of writer’s block. I just sort of did it. I didn’t do it on a regular basis the way some people do, but I did it. During the horrible Trump years, and then with the lockdown, I had trouble working because it was very hard focusing on what seemed unimportant considering everything else that was going on. On the laptop, you write a sentence, you look at it, and you think, “This is the worst sentence ever in the history of the world.” You erase it, you write another sentence, and then you think, “Nope, that’s the worst sentence ever written.” Finally I figured out that if I use a pencil, a really bad pencil, and just sit and write in a notebook without thinking too much, it kind of gets me going.

How did you get interested in writing about this era and this group of emigres?

I was writing a book review of a biography of Alma Mahler, Gustav Mahler’s wife. If you look at her love affairs and marriages, you have a picture of early 20th-century modern culture. For a long time she lived in Los Angeles. I got so interested in the period, and started reading about all these other people who were here. I hadn’t realized there was this incredible intellectual and cultural community that was referred to as “The Colony.” They all spoke German, and they met up and helped each other out.

I also wanted to write about Los Angeles, and as a relative newcomer I didn’t know how. It takes me a long time to feel comfortable writing about a place. So it presented this wonderful possibility. But I didn’t want to write a historical novel, because they get so fussy. So when Julian came along in my head, I was so happy to see him and realize that his grandmother was going to tell him these stories.

What was it like putting yourself into the mind of Julian, who is just coming of age at the time of the pandemic?

At first I resisted it, but then I really got interested in how he would be reacting to all of this. He drew me in. At one of the readings, my younger son said in the questions, “Did you have any real-life models you drew on for Julian?” and the truth is yes and no. Of course I use every scrap of anything from any young person I know. But some of it was just from when I was young: the entitlement, the certainty about everything that you have when you really know nothing. I remembered things from my youth that helped me understand Julian and his discomfort with growing up.

So much of Kunstlers in Paradise is about Julian situating himself in history. Naturally, he does this by comparing what he’s going through to what his grandmother went through, and then flagellating himself for making inappropriate Holocaust comparisons. I wonder what you think of that impulse and when it really is OK to compare something to the Holocaust.

You can’t help but make comparisons — but with all proportions kept. The parts that seem so parallel are the early days, starting in the ’20s and into the ’30s, with the rise of Hitler and the way people sort of didn’t want to know, and the gradual move towards fascism. You can’t help but notice the parallels. To say that this country is the same as Germany in the ’30s is obscene, it’s not. But it has tendencies. For me it’s a matter of proportion, and of opening your eyes and seeing that things look similar, but that it’s also not the same.

It’s striking to me that even though you started this book thinking about the society of emigre exiles, the main character is very much Mamie. Why are her parents, the intellectuals, so secondary?

To have a child’s point of view for someplace new is wonderful, and opens up the book in a very particular way. But I also wanted her to be grown up and old and still alive now. Maybe, in the beginning, it was a kind of caution on my part. It’s hard to be in another historical era comfortably and authentically. Writing from a child’s point of view made that possible, because there was a certain naivete built in. So partly it was just a pragmatic thing. But those pragmatic things usually appear to you after the other reason, which was a child coming to LA and seeing all this.

Künstlers is peppered with real celebrities who appear in Mamie’s life. One of them is Greta Garbo, and without giving away any spoilers, I want to talk about the romance that develops between them as Mamie grows up. It’s really the crux of her own story, but she doesn’t want to talk to Julian about it.

This was Mamie’s story and her secret. She was happy to share a lot of things. But there are certain stories that you don’t tell, that are precious and held in your heart. The whole scene of it was inspired by something written by Mercedes de Acosta, who was this radical lesbian. She wrote some screenplays, but mostly she walked around in black and white and a three-cornered hat, and she was obsessed with Greta Garbo. Whenever there’s a story about the sex life of someone who is revered that doesn’t perfectly fit the legend, people say, “Well, you know that probably didn’t happen.” So there are all these memoirs from different people, men and women, having encounters with Greta Garbo, and the biographers are like, “Well, that probably didn’t happen.” But with her you never know, because she really was nuts.

What do you do to wind down after a day at work?

This is something the pandemic really changed, which is that cocktail hour starts at 4 p.m. Which is the perfect time to watch the Mets if you’re in Los Angeles. So the day ends early, and I have my little glass of Jack Daniels, which my grown children tease me about endlessly.