Coffee and cigarettes: An essay by Etgar Keret

On Israel, family and the value of a good cup of coffee

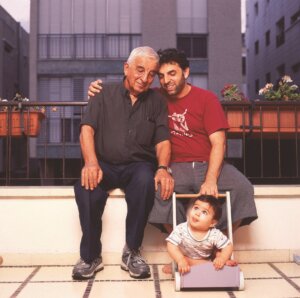

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The question I have been asked more than any other in my adult life is, “which authors have influenced your writing?”

As with any frequently asked question, I have a stock answer. It begins with Franz Kafka and Sholem Aleichem, and ends with Janet Frame and Kurt Vonnegut.

But if I am being real, there are two people that — although they have not published so much as a pamphlet in their entire lives — have influenced my writing more than all the other authors combined: My mother and father.

My parents, both children of war, had to use everything they had to survive. And what they had wasn’t much. Although they lacked food and warm clothing, whether in hiding or in the ghetto, they drew from a secret mental stash, the last remaining resource that soldiers were unable to steal or confiscate: their imagination.

This year, Ira Glass dedicated a program to my mother, of blessed memory, and the special way in which she told the story of her life — and how, over the years, that informed my own writing style.

My father, of blessed memory, also taught me quite a few things about imagination as a means of survival. I learned from my father, from infancy, that at the heart of the stormy and violent ocean of existence lies within you, always, a buoy. Yes, one that you have to reinvent time and again. But, still, one on which you can float until you reach a safe shore.

On the fraught and discouraging 75th birthday of the State of Israel that we’re celebrating this year, we still haven’t reached those calmer shores. But with the help of my father’s compass of imagination and optimism, I will keep trying. I will remember the important lessons that I learned from my father about stories, imagination and hope.

When I was 6 years old, my dad worked at a pool snack bar, not far from one of Tel Aviv’s beaches. Every day, at 5:30 in the morning, he’d leave home for the pool, swim two kilometers, shower in the warm members-only locker room, and get to work. He wouldn’t get home till nine at night. Fourteen hours a day, seven days a week, unloading boxes of soft drinks, pressing toasted sandwiches, brewing coffee in gleaming glasses at the pool snack bar, up by Gordon Beach.

Years later, Dad always said those were the best days of his life, fondly remembering how the salty air blowing in from the sea would mix in his lungs with the smell of the coffee and the imported cigarettes he used to sell at the bar. Coffee, cigarettes and the sea were always my father’s three favorite things.

For me, those days were not quite as happy. When Dad came back from work, I was already in bed, and other than Saturdays, when I’d go off to visit him at the pool with Mom, I never saw him at all. Not that I was bitter about this. Six-year-old children can’t really imagine a different world for themselves, one where their father has more time for them; they accept reality as it is. And yet, I missed him dearly. Seeing this, my mother suggested I go with him every morning to the pool, have a swim together, and take a cab to school from there.

Besides the slap of cold I suffered every day, jumping into the frigid water, I don’t remember anything of those morning swims, but the car rides with Dad are crystal clear: It’s still dark out as we sit in our silver Peugeot 504, the windows rolled down, Dad smoking Kent 100s and describing parallel universes that exist at this very moment in other dimensions, universes where everything is precisely identical to ours — same road, same traffic light, same cigarette in the corner of Dad’s mouth — all except for one tiny difference. And this difference, Dad would switch out every morning, changing the one detail in the parallel universe that differed from ours: Here we are, in a parallel universe, waiting at the exact same intersection for the light to change, only in this universe, instead of a silver Peugeot, we are riding a dragon. And here’s another one, where under my faded sweatpants hide gills, which will soon allow me to breathe underwater, like a fish.

Join author Etgar Keret for a conversation about Israel at 75. Learn more ➤

When I was 9, my father got a new job. He no longer had to get up so early in the morning, and in the evenings, we’d all have dinner together and watch the nightly news. I was 22 by the time I moved out of my parents’ house, but I still made sure to visit them at least twice a week, and on Saturdays I’d swim with Dad at the pool where he once worked. When I was 43, my father was diagnosed with cancer. It was tongue cancer, the result of 50 years of smoking. By the time the doctors caught on, it was at an advanced stage, and though we never spoke a word about it, it was obvious to us both that he was going to die soon.

On Mondays, I’d take him in for his physical therapy, and as we sat in the waiting room to see the physical therapist with the British accent, my father sometimes still talked about parallel universes where everything was exactly the same as ours, save for one difference. Say, that dogs could speak. Or that people could read minds. Or that the sky was purple, a deep shade of beet, and when the milk white clouds floated across it, they looked tasty enough to eat.

At the end of every session, the physical therapist would show me how to hold my father’s arm when we walked together, and what I should do in case he lost his balance. On our way home, as we approached the corner of King Solomon and Arlozorov, Dad would always stop. “Do you smell that?” He’d say, and point to the new café on the corner. “Just by the smell of it, I can tell you, that’s the best coffee in town.” At this stage of his illness, the tongue cancer was so advanced my father could no longer eat or drink. Instead, he got all his food and liquids through a clear plastic tube, straight to his stomach.

On one of these Mondays, after physical therapy, while walking by the corner café on King Solomon and Arlozorov, my father, instead of just pausing to praise the place as usual, suggested we actually go in for a cup of coffee. “Dad,” I said, after a moment’s hesitation, “You can’t drink anything. The tumor is blocking your esophagus.”

“I know,” he said, and patted me on the back. “But you can.”

We sat at a corner table on the sidewalk. I ordered a latte and a glass of water from the pretty waitress, and when she asked my father what he’d like, he asked for a double espresso. I stared at him — confused — and he smiled and shrugged. The waitress noticed Dad’s guilty smile, and gave me a questioning look. Not knowing what to say, I ordered an oatmeal cookie.

Until the coffee arrived, we sat in silence. I wanted to ask my father why he’d ordered coffee at all, and if it had anything to do with the waitress being pretty, but I said nothing. Dad pulled the cigarette pack out of his shirt pocket and the lighter he had stored in his glasses case and set them both down on the table. We waited.

A few minutes later, the waitress returned with our order. She placed our order on the table: a latte, a glass of water, and a cookie on a plate in front of me, and a double espresso in front of Dad.

Aromatic steam rose from my coffee. I wanted to drink it, but doing that in Dad’s face seemed unfair, so I just kept staring at it, when, out of the corner of my eye, I saw my father quickly snatch the double espresso off the table and gulp it down in one sip.

It was impossible. I knew it was impossible. After all, I was there in the room when the oncologist showed me and my mother the X-ray with the tumor resting above the blocked esophagus, like a scoop of vanilla ice cream on a waffle cone.

My father, she said then, could never drink again. And here we were, sitting together on a pleasant summer day, at this hipster café, me still staring at my steaming cup of coffee and him, by my side, smiling after killing off his double espresso, and for a moment there I thought, maybe we were in a parallel universe, maybe he’d told me enough stories, ever since I was a little boy, to tear open a hole in the aching heart of our universe, through which we were sucked into a parallel one, identical to our own in every way, save for one exception — in this universe, my Dad could drink and eat as much as he liked, and he was not about to die in just a few months.

The piping-hot coffee slid down my father’s windpipe and into his lungs. When it got there, Dad started to choke. He stood up in the middle of the café and grabbed his throat with both hands. The wet wheezing noises he made were horrific, the sound of a man whose lungs are flooded with hot coffee. The waitress looked over in horror. A bespectacled man from the table next to us leapt up and asked my father if he needed any help. I just sat there, paralyzed. The parallel universe I’d shared with my father moments ago had vanished, dropping me back into a far worse universe. A few more seconds of gargling followed, after which Dad leaned over and spat onto the café floor, evacuating all of the fine Italian espresso that had filled his lungs. When he was done, he sat up in his chair as if nothing had happened, centimeters away from the puddle of coffee and phlegm, and lit himself a cigarette. People at the tables around us kept staring at him, mesmerized.

“What did I tell you?” He smiled at me and exhaled smoke from his nostrils. “The best coffee in town.”

This essay originally appeared on This American Life. It was translated from the Hebrew by Jessica Cohen. The headnote was translated by Laura E. Adkins.